To save the planet, mankind must rapidly reduce its greenhouse gas emissions. But where should we be reducing those emissions from? What would make the biggest difference?

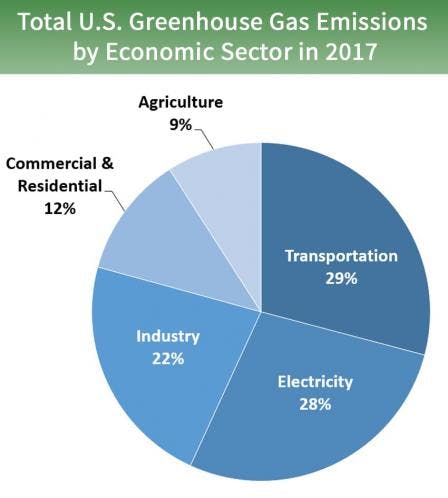

Journalists and environmentalists often answer that question by looking at which sectors of the U.S. economy contribute the most to global warming. The transportation (cars, buses, trucks, and planes) leads in greenhouse gas emissions, while electricity (coal and natural-gas power plants) is a close second. Industrial goods and services are third, buildings fourth, and agriculture fifth.

This way of measuring blame, however, misses something crucial: people. These industries are spouting carbon because customers demand their products: travel, electronics, entertainment, food, all sorts of stuff. So what if, instead of solely measuring emissions by economic sector, we looked at consumer demand within those sectors?

Researchers have done just that, and the results tilt the question of blame away from businesses and toward a different villain: ourselves.

C40 Cities, a network of 94 of the world’s biggest cities, released a report on Wednesday estimating how much consumption habits drive the climate crisis. The results were staggering: In those nearly 100 cities, where a combined 700 million live, the consumption of goods and services “including food, clothing, aviation, electronics, construction and vehicles” is responsible for 10 percent of global greenhouse gases. That’s nearly double the emissions from every building in the entire world.

If consumption-based emissions in those big cities continue on their current track, they will “nearly double between 2017 and 2050—from 4.5 gigatons to 8.4 gigatons per year,” the report says. That means the cities would not be able to achieve reductions necessary for the world to stay below 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming, which the scientific community says is necessary to preserve a livable planet. In fact, they would use up their budget for that target in the next 14 years.

For cities to do their part to limit global warming to 1.5°C, the report says, they must limit their consumption-based emissions by 50 percent by 2030, and 80 percent by 2050. That will be extremely challenging. It will require changes in how goods and services are produced on the industrial level, which will likely require policy intervention by national governments. Scientific advancements must be made as well, including “sweeping decreases in the carbon-intensity of industrial processes such as the making of steel, cement and petrochemicals,” the report reads.

There will be little incentive for businesses and governments to make these changes, however, if the people who support them—with dollars and votes, respectively—aren’t also making it a priority.

“Individual consumers cannot change the way the global economy operates on their own, but many of the interventions proposed in this report rely on individual action,” the report reads. “It is ultimately up to individuals to decide what type of food to eat and how to manage their shopping to avoid household food waste. It is also largely up to individuals to decide how many new items of clothing to buy, whether they should own and drive a private car, and how many personal flights to take.”

And this individual action must occur collectively. Put more bluntly, it will require personal sacrifice from our entire society. We will have to fly less, drive less, Uber less. We will have to eat less red meat, drink less dairy, waste less food, and generally buy less crap that we don’t need.

A lot of Americans won’t want to do this! So our government may have to compel it, whether through the Green New Deal or some other legislation. Some countries are already taking small steps to address “throwaway culture”: Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said Monday that Canada will ban single-use plastics as early as 2021. But if the world is to stand a chance, the U.S. will have to taken even bigger steps—nothing short of a wholesale rejection of modern American consumerism itself.