I first met Bill Baird in Hempstead, Long Island, on a freezing December night in 1968. This was 18 months after he was arrested and jailed for handing a can of contraceptive foam to an unmarried coed at Boston University. And it was some four years before the Supreme Court would hand down its decision in Eisenstadt v. Baird, the case that grew out of Baird’s illegal action and established the right of unmarried people to possess contraceptive products. Eisenstadt, in turn, was a crucial privacy precedent that the Court cited in 1973’s landmark Roe v. Wade decision establishing a woman’s right to an abortion. But on that night in 1968, Baird was attending to more immediate matters: a clinic packed with desperate women.

Until three in the morning, I listened as Baird counseled them on birth control and provided names of doctors who would perform abortions. I was writing about illegal abortions for The Washington Post, a series that was considered daring in those days. I had already detailed several cases of death due to back-alley abortions, and the atmosphere surrounding the procedure was shot through with fear. Assistance for women was totally underground, and dangerous; there were no other public referral services like Baird’s in the country. “Women today have no idea what it was like back then,” Baird told me earlier this year, when we reconnected over the phone.

His clinic was filled with Catholic mothers. There was a pregnant housewife, a mother of five, who told me, “I don’t believe it’s the Church’s duty to tell me how many children I should have—the Church won’t feed them or send them to college. And it’s not the state’s right either.” There was also a 19-year-old daughter of a small-town mayor who was holding hands with her boyfriend; her family doctor would not give her birth control pills without her mother’s consent: “She refused,” she said. Another woman was hunched in a corner, wearing a faded green blouse and skirt. She was a candy packer in a New York factory, making about $60 a week—an unmarried mother of four, pregnant again, who spent most of her paycheck on a nanny so she could work the night shift.

She was considering a back-alley abortion. “There’s a lady around the corner who charges $50 to $100,” she said. Baird admonished her, “You could be dead. Don’t go to those people.” Baird sent all the women to doctors he deemed reputable. He took no money. He never heard back from the thousands of women he counseled, nor heard about any complications or disastrous outcomes. “I assume I would have,” he told me.

Baird

became an abortion-rights crusader—or extremist, many at the time would have

said—after visiting

Harlem Hospital in 1963 as the clinical director for EMKO, a birth control

manufacturer. There he saw a dying woman stumble into the corridor and collapse

on the floor, soaked with blood from the waist down, a coat hanger embedded

deep in her uterus. “I rushed over and held her,” he said.

That moment was Baird’s catalyst for action. By the time we met five years later, Baird had a string of prison sentences that would awe a hardened jailbird. He’d been arrested in New York, New Jersey, Wisconsin and thrown out of shopping malls for trying to distribute birth control information. He’d also been arrested in ghettos for peddling birth control information in his delivery truck, nicknamed the Plan Van. After Roe legalized abortion, he ran three clinics and provoked anti-abortion evangelists by picketing their conventions, carrying an eight-foot cross emblazoned with the message: “FREE WOMEN FROM THE CROSS OF OPPRESSION. KEEP ABORTION LEGAL.”

For his efforts, he endured years of death threats, violent attacks, and public enmity, sometimes even from his own ostensible allies in the abortion rights movement. His influence, though, is hard to overstate. Once known as the father of abortion rights, Baird’s often extra-legal actions also led to numerous other privacy rights laws and the legalization of same-sex marriage. Roy Lucas, the lawyer who helped fashion the right-to-privacy argument that took center stage in Roe, characterized the Supreme Court decision in Eisenstadt as “among the most influential in the United States during the entire century.”

Today, Baird laments, “no one knows I exist.” Indeed, millions of single women who take the pill, same-sex couples who are legally married, and women who have known nothing but legal abortions for nearly 50 years, have no idea that an 87-year-old man who is half-blind, broke, and in poor health helped secure those freedoms—freedoms that, in the age of Trump, they are dangerously close to losing. And many of Baird’s unwitting beneficiaries have also forgotten the main lesson of his brand of aggressive activism: that “extremism” can be an effective force behind genuine, long-lasting, badly needed change.

Baird was born in Brooklyn in the deep depression year of 1932, one of six children. His strict Lutheran mother was often drunk. His father was a drunk as well, and mostly absent. When his father was home, he would beat Baird’s mother. “She gave as good as she got,” Baird noted. “She could beat my father up when he was drunk and couldn’t defend himself.” Baird’s mother was verbally and physically vicious. “One day when I was just a little kid,” he said, “I put an egg on top of our coal stove. I thought the heat would hatch the egg and it would become a chicken. My mother yelled, ‘How dare you take our food?’ She put my hand on the hot plate as punishment.”

Baird scraped together money for his family by

“junking,” or scavenging in rubble and garbage. “I went from garbage can to garbage can, collecting newspapers

and anything that could be sold. I would take wagon load after wagon load to the

junk yard,” he said. “I got 75 cents for 100 pounds.” Baird became “a strong

street fighter” among the scavenger gangs that prowled the makeshift shacks and

the railroad tracks, tussling over empty cigarette wrappers. “You got money for

a ball of foil. If I found a piece of hard cardboard, I used it to cover the

holes in my shoe soles.” A recovered patch of linoleum was heaven.

When Baird was nine, an older sister of his died of a cerebral hemorrhage—an experience that seared him emotionally and fostered his lifelong rebellion against authority and religion. “‘If there is a God, why should she suffer?’ I thought. Here was my beautiful, kind, smart sister, dead and all because we didn’t have money for a doctor.” He is estranged from his surviving siblings. “A sister still works for the Republican Party,” he said. “They are all conservative except me.”

Baird graduated from Brooklyn College in 1955. He married that same year, then dropped out of New York Medical College in 1963, when he was forced to choose between books and food for his three children. In 1971, after too many death threats for his abortion work, Baird moved his wife and children away for their safety. That absence led to divorce. Baird says this is the saddest price for his unrelenting activism: “I lost them all. The kids grew up in a Catholic community. My granddaughter says I murder babies.”

As he embraced an activist career, Baird also mastered the flamboyant art of headline-grabbing, using the media to publicize his cause. He knew precisely what he was doing with that famous can of contraceptive foam in 1967, in the dark ages of bans on birth control. “Police were standing around, with guns,” Baird recalled. “I reached down to an unmarried coed and gave her the can of foam.” A restive crowd at the Boston University event, estimated at upward of 1,500 students, jeered the police as they moved to handcuff Baird. “I pulled my hand away and silenced the crowd,” he said. “I took out the sales receipt from Zayres, the store that had sold me the foam. It was a cost of $3.00 with a charge of nine cents for sales tax. I said, ‘Now how can the state collect tax from an “illegal” sale?’”

Tabloid headlines made the most of it: “VICE SQUAD NABS BU BIRTH CONTROL SPEAKER.” Baird was led away to prison, and charged with violating a 19th century law still on the books that punishes crimes against “chastity, morality and decency.” If he had lost the case, Baird could have been sent to prison on multiple counts for a combined 10 years.

Baird remembers the innocent-looking candy bar on his cell cot his first night in Boston’s brutal Charles Street prison, where he served 36 days of a three-month sentence before being released on appeal. “Beside the candy bar was a note [from a friendly inmate] warning me to throw it on the floor, stomp on it, ‘Whatever you do, don’t eat it. That means you would be a “sweetheart” to someone.’” Baird’s rough Brooklyn childhood served him well in prison. “I was good with my fists,” he said. “They left me alone.”

As he recalled his time in Charles Street, the garrulous Baird grew silent. Then he said, “They gave us tin cups to rattle on the bars of our doors to call a guard if you were being attacked or ill.” He paused. “All these years later I can still hear that sound, that rattle for help in the night.”

As Baird brooded over his prospects in his cell, where rats crawled in corners and bugs lurked in his food, he gradually elected to go for broke, and launch a series of legal appeals in the hopes of bringing a test case before the U.S. Supreme Court. “I had about a 98 percent chance of being rejected by the Supreme Court and a two percent chance of being heard, but I thought I had to try,” he said. He hoped that a precedent had been set by a landmark Planned Parenthood case two years before, Griswold v. Connecticut, in which the Supreme Court struck down an arcane Connecticut law barring the dissemination of contraceptive information or devices, saying it denied the right of privacy—but only to married couples.

Baird’s case was riskier, pushing against religious “morality” standards for unmarried women. Eisenstadt v. Baird was finally heard by the Supreme Court in 1972. Justice William J. Brennan’s legendary wording in overturning the law was crucial: “If the right of privacy means anything, it is the right of the individual, married or single, to be free from unwarranted government intrusion into matters so fundamentally affecting a person as to the decision whether to bear or beget a child.” That precise language—to bear or beget—led directly to Roe ten months later. Eisenstadt was cited five times in that majority opinion.

Baird, who never studied law, has two other Supreme Court

victories bearing his name: Baird v. Bellotti I (1976) and Baird v. Bellotti II (1979), which gave

minors the right to abortion without parental consent. (These decisions have

since been largely eroded by state laws.) Eisenstadt has also been cited

in more than 52 Supreme Court cases from 1972 through 2002. All eleven U.S. Circuit Courts of

Appeals, as well as the Federal Circuit, have cited Eisenstadt

as authority. In this century, Eisenstadt was again cited in Obergefell v. Hodges, the 2015 ruling that

legalized same-sex marriage.

At this stage of life, Baird could rest content with a wide-ranging legacy as a privacy and abortion-rights activist. Instead, he remains obsessively bitter about the scornful way he was treated by some leaders in the abortion-rights movement. “They did their best to make out I was crazy,” he told me. He remembers every ancient slight. An abiding anger against Planned Parenthood began when the organization refused to help him after he was arrested at Boston University in 1967. The group instead sent out a bulletin dismissing Baird: “He is in no way connected with Planned Parenthood.” For good measure, the disclaimer added—quite mistakenly as it turns out—“There is nothing to be gained by court action of this kind.”

Baird says he had also hoped for financial support from the ACLU. But it never came. “There I was,” he recalled, “having three young kids to support, and in jail.”

An unconscionable slight was a 2015 Planned Parenthood article celebrating 50 years of legal birth control and the vast numbers of women who have achieved higher education, careers, jobs, and planned pregnancies as a result. Although the heroic chronicle made much of the less significant Griswold decision for married women, it never once mentioned Baird’s historic victory in Eisenstadt.

Sloppy reporting also manufactured feuds. For example, a 1993 New York Times article, without attribution, said that the feminist icon Gloria Steinem “refused to shake his hand”—an episode that both deny ever happened. “I don’t remember meeting Baird, much less refusing to shake his hand,” Steinem told me in a recent email.

On the other hand, the late Betty Friedan, author of The Feminine Mystique and founder of NOW, was one of Baird’s genuine nemeses. She bizarrely suggested that Baird was a CIA plant, sent to undermine the abortion-rights movement. Years later, when a reporter asked about Baird, she slammed the phone down after shouting that he was “irrelevant.” (Friedan had other enemies: She was appalled at the emergence of lesbians in the movement and feared that they could inhibit mainstream support. She famously tagged them “the Lavender Menace.”)

Kate Michelman, the director of NARAL for 19 years starting in 1985,

scoffs at Friedan’s opinion of Baird. “Eisenstadt v. Baird was huge,” she told me. “Griswold helped only married women while

Baird gave privacy rights to

all of us unmarried.”

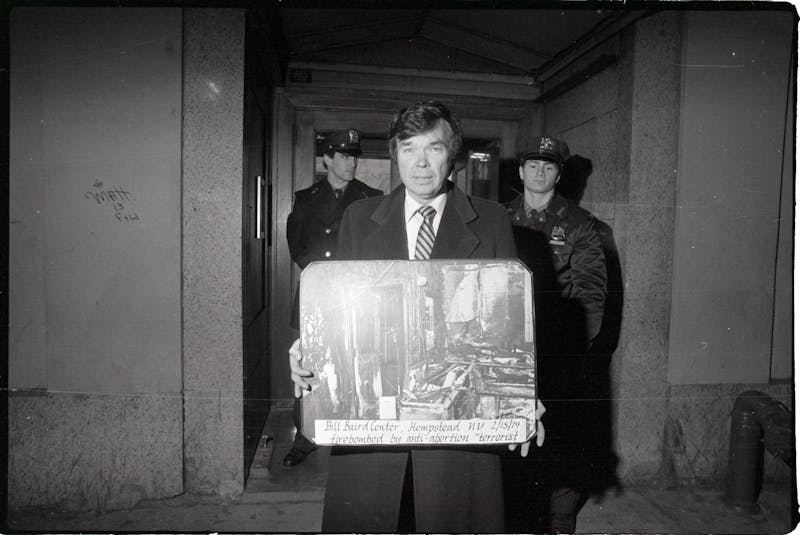

If Baird’s actions were once considered extreme, they pale in comparison to the genuinely extreme, often violent measures taken by his opponents in the anti-abortion movement. There was, for example, the bullet that tore through his living room window. There was also the torching of his Long Island clinic in 1979. A staffer answered a knock at the door, and “this 25-year-old man carrying a full can of gasoline and a long flaming torch walked into the reception room,” Baird recalled. He sloshed gasoline on the carpet and set it aflame. Some 50 staff members and panicked patients fled into the cold afternoon. Flames rose quickly, heavily damaging Baird’s two-story twelve‐room clinic.

The arsonist, Peter Burkin, fled but was quickly captured. He suffered second-degree burns on both hands but, amazingly, everyone else escaped unharmed, thanks to Baird’s training drills. To simulate escaping in blinding smoke, staffers were blindfolded and crawled on their knees to locate exits.

When he came up for sentencing, Burkin was put in a mental hospital. With his clinic under constant threat, Baird wrote the nation’s first clinic self-defense manual to combat anti-abortion terrorism.

Baird tried and failed to make the FBI view such violent attacks as acts of domestic terrorism. Today, he says angrily, “If you firebomb a post office, that’s a federal offense. If you firebomb an abortion clinic, it’s a ‘political statement.’” He was appalled when the Supreme Court in 2014 overturned a Massachusetts law establishing a buffer zone around abortion clinics, calling it a “horrendous day” for women’s health and medical privacy.

In addition to the extremists who have bombed scores of abortion clinics and murdered at least eleven abortion doctors and clinic workers over the years and injured many more, anti-abortion warriors engage in aggressive psychological warfare, targeting vulnerable patients. A recent PBS Frontline documentary featured a contingent of older Catholic men picketing a Philadelphia clinic with a huge sign that announced, “BABIES KILLED HERE.” Women seeking abortions ran an intimidating gauntlet of picketers shouting, “If you took the abortion pill, we can reverse it,” while signs said, “Please mommy, let me live.”

This belligerent mode of anti-abortion protest supplies some crucial context for Baird’s own brash style of activism, which emphasizes confrontation, contrast, and righteous indignation. It’s an approach that remains too extreme for mainstream abortion-rights groups, which have been reluctant to go on the offensive, even as their opponents ratchet up their rhetoric and score major legislative victories in the campaign to shut down access to abortion in many states. Just recently, Planned Parenthood was embroiled in a debate about whether it should “politicize” the issue of abortion or emphasize that it is merely a health-care procedure. The former argument won out, producing the ouster of the group’s moderate incumbent president, Leana Wen, but the controversy still shows the extent to which the abortion-rights movement is consumed by debates over moderation, civility, and reaching out to the “other side.” Baird holds no such illusions.

The day after Roe became law, Baird predicted that the opposition, led by the Catholic Church, would never stop until the decision was struck down. He has been battling against that backlash ever since—and watched it gain significant ground since the election of Donald Trump, who has managed to install two anti-abortion justices on the Supreme Court and has overseen anti-abortion measures proliferate in red states.

“I wish that that sexist Trump and all of those other old white men would have just one giant menstrual cramp so that they can even begin to understand what it is like to be a woman,” he told me, his voice quivering with outrage. “Women are going to die again because of these old white sexist men—the Catholic Church, the extreme Evangelicals and their lawmakers. We could lose Roe v. Wade. I have been saying this for decades as restrictions have been placed on abortion rights—and nobody listens.”

Conservative legislatures—emboldened by Trump’s Supreme Court appointments and his outrageous lies about abortion providers “ripping babies” from mothers who “execute” their living children—have passed or introduced state laws that criminalize abortion after six weeks. That cutoff date comes at a point before most women even know they are pregnant. By May in 2019 alone, nearly 30 abortion restrictions had been introduced across the country. More than 400 state-level abortion restrictions have been enacted since 2011.

As it continues to rack up victories, the anti-abortion movement has only grown bolder and more relentless, with sophisticated websites and thousands of Crisis Pregnancy Centers across the country seeking to discourage women from going through with abortions. Moreover, these centers refuse to offer birth control advice or contraceptives, which could have stopped the unwanted pregnancies of the many women they see who already have multiple children. And in a vicious cycle, their activism fuels more aggressive anti-abortion measures from state lawmakers.

Meanwhile, Planned Parenthood has

been squeezed by Trump’s so-called gag rule, which makes it illegal for health-care providers in the Title

X funding program to refer patients for abortion care. Planned Parenthood was

thus recently forced to opt out of federal funding under Title X—a massive blow to health care

access for poor women. The affordable birth control that Title X provides helps prevent one

million unintended pregnancies each

year. Four million people rely on Title X for access to

contraception and reproductive health care.

Kate Michelman, the former director of NARAL, has dedicated her life to birth control and abortion-rights battles. She says that we are now “revisiting a nightmare” that she thought was long over. Her voice rises with concern about those who are most vulnerable. “For working-class and poor women and women of color the blatant assault on access to contraceptives and abortion will have an extraordinary impact,” she told me. “The very real possibility that Roe v. Wade will be overturned sends shivers down my spine. Roe saved women from the degradation and shame of back-alley abortions where women were forced to risk their lives in order to take control over their lives.”

Like thousands of women, “I don’t think I understood,” Steinem told me, the “deep and long-term opposition when Roe v. Wade was passed. I thought it was just a commonsense and majority-supported way of making abortion safe and legal.” She added, “Now, despite the fact that a majority of people in this country agree that abortion should be safe and legal, patriarchal political and religious groups keep right on trying to make it illegal. Both white nationalists and evangelicals are controlling some state legislatures and supporting Trump on this issue alone.”

Abortion is shaping up to be one of the most urgent issues at stake in the 2020 election. The Supreme Court announced on Friday that it would hear June Medical Services v. Gee in its upcoming term, “a case that could well be the vehicle the Court’s conservatives use to gut the right to an abortion,” according to Vox. But it remains to be seen what course Democrats and abortion-rights groups will take: whether they will continue to quietly fundraise off Trump’s anti-abortion politics or whether they will finally match a decades-long, all-out Republican offensive that has resulted in a federal judiciary and statehouses across the country heavily tilted toward the right on the issue. “We could see these [abortion-rights] groups mobilizing county by county but often we didn’t have the money to be everywhere,” Michelman said. NARAL now begs for funding to pay for a “major expansion to our grassroots organizing team.”

Baird is now married to Joni Baird, who met him in 1997 when she “applied for a job as an assistant,” she told me. “From the second we began working together we were like one person. I think I fell in love with him when I saw him playing Santa, which he did for decades, collecting thousands of toys for needy children. Who could not love a heart that golden?”

The two of them operated the Pro-Choice League until financial viability problems and ill health came their way. Although Baird says they are broke, Joni, who is 25 years his junior, corrects him: “We get by,” she said. Baird has severe macular degeneration and recently had a successful cancer operation. “He dodged another bullet,” Joni happily noted. Baird said of Joni, “She is the only person who really loved me.”

They take little satisfaction from the fact that mainstream abortion-rights organizations have finally caught up to what Baird has been saying all along: that their complacency about Roe would one day come back to haunt them. Baird, for his part, is still mad as hell, still militant as ever. He accomplished so much on his own—now just imagine what the world would look like if he had had a little more help.