Not long before Margaret Thatcher’s intensely dramatic departure from office in November 1990, the veteran Conservative politician William Whitelaw was talking to Sir Robin Butler, recently appointed as Cabinet secretary, the most senior permanent official in the British government. As Charles Moore relates in Herself Alone, the third and final volume of his authorized biography of Thatcher, Butler was taken aback by what he heard. “The trouble is,” Whitelaw said, “that when Margaret leaves, she will leave the Conservative Party divided for a generation.” Not only did Whitelaw’s prediction come to pass. The longer legacy of her career and its finale haunts both Moore’s book and David Cameron’s memoir For the Record. And the great question dividing a United Kingdom that is now as disunited as could be is, of course, Europe.

Beginning with the postwar period, when a ruined and demoralized continent started to rebuild itself through close cooperation among countries, the British could never decide what their relationship with that new Europe should be. That was so from Winston Churchill’s oracular “with them but not of them” to two failed attempts to join the Common Market or European Economic Community in the 1960s, to joining at last in 1973, to the first referendum confirming membership in 1975, to Thatcher’s fierce battles with European leaders in the late 1980s. It continued with the brutal intestine conflicts that beset the Conservative Party after her fall, with Cameron holding what his chancellor, George Osborne, called “your fucking referendum,” with the unexpected victory of Leave in June 2016, and finally with the political and constitutional crisis that has engulfed the country since then.

Over 50 years, every Conservative prime minister has been ruined one way or another by Europe. The referendum has left the British government and people not only polarized but paralyzed, reflecting on the dismal shortsightedness of our politicians, who quite failed to foresee these consequences. Like Thatcher’s, Cameron’s government was riven with internal conflicts over Europe. Like her, he left Downing Street in personal defeat and humiliation amid accusations of betrayal. Unlike her, he will never be remembered for any profound achievements, one way or another, for better or for worse.

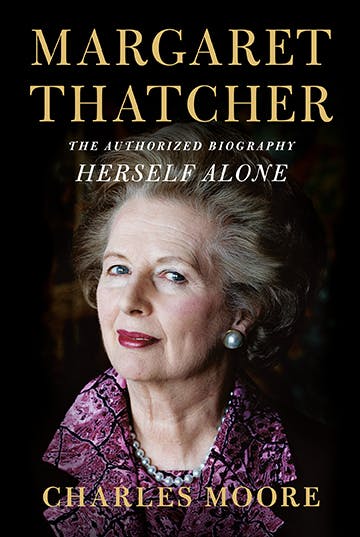

In the first volume of his formidable and outstanding work, which has been 20 years in the making and now weighs in around 2,500 pages and well over a million words, Moore told the story of how a girl called Margaret Roberts came from the small town of Grantham in Lincolnshire, the daughter of a Methodist shopkeeper and lay preacher, to make her way to Oxford in the 1940s and up through the ranks of the Conservative Party in the 1950s. Mrs. Thatcher—as she is respectfully called throughout a book in which others are generally referred to by surname only—seized the leadership of her party in 1975, became the first party leader of modern times to win three consecutive general elections, and held office longer than any premier since the advent of universal suffrage. Whatever one’s view of her or her politics, it’s fair to say that she led one of the only two British governments since the war to have changed the political landscape, the other being Clement Attlee’s Labour government of 1945 to 1951, whose work she devoted herself to undoing.

And yet, while Moore’s second volume ended with Thatcher’s second election victory in 1987, it ended also with a warning. A large part in this story is played by Charles Powell, a Foreign Office man who became her private secretary in 1983. That’s an official appointment, but Powell became much more, her consigliere and intimate, acting in a way that often went improperly well beyond his supposed duties, encouraging her in her feuds with colleagues, to the point that Butler threatened to resign unless Powell were removed. Powell congratulated her on her victory, but “all the same,” he told her, “I hope you will not put yourself through it again.” At some point soon, her “reputation and standing as a historic figure” would matter more than anything more she might do. “Your place in history will be rivalled in this century only by Churchill. That’s the time to contribute in some other area!” This clear intimation of her political mortality was seconded by Denis Thatcher, her husband, who urged her to leave at the latest in the spring of 1989, after ten years in office.

By now, not only her foes in the Labour Party and the liberal media but others had begun to tire of her imperious manner. The first chapter of Herself Alone is entitled “Bourgeois triumphalism,” a phrase coined (to the delight of the Left) by Peregrine Worsthorne, High Tory editor of The Sunday Telegraph, intending not only Thatcher herself but the vulgar greed-is-good spirit of the newly deregulated City of London. Maybe she could cope with that barb, but her position wasn’t as impregnable as she was lulled into thinking. One row in particular helped end her career. A flat-rate tax to fund local government in place of the rates levied on property was officially the “Community Charge,” but was generally known—and hated—as the poll tax. Although Moore is a true believer (at one point he suggests that “Margaret Thatcher was the greatest genius ever to direct the affairs of the United Kingdom”), even he knows that she stayed on too long, exhausted her electoral capital, and lost her affinity with a British people who had never loved her but had, many of them, admired and supported her.

Looming over all domestic questions was Europe. Thatcher’s relations with the European Economic Community (as it then was) were complicated. In 1975, she was photographed in a fetching sweater patterned in European flags while campaigning to stay, and in 1986 she signed the Single European Act, whose purpose was to strengthen the European Monetary System with its Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM). At that time, the cause of European integration was strongly favored by the Foreign Office, indeed most of the establishment, including many Tories. Three people had been at the heart of the free-market, low-tax, privatizing “Thatcher revolution”: Thatcher herself; Geoffrey Howe, her first chancellor (and later deputy prime minister); and Nigel Lawson, her chancellor from 1983 to 1989. Howe was an enthusiastic European who wanted to join the ERM, and although Lawson was less committed, he began a policy of “shadowing the Deutschmark,” or pinning sterling to the strongest European currency, as a means of controlling inflation, which he did without telling Thatcher. Meantime she was increasingly hostile to Eurocrats like Jacques Delors, the president of the European Commission, who were pursuing their hoped-for centralized superstate, and skeptical about premature plans for monetary union.

As a somewhat tepid or critical Remainer, let me say that Thatcher sometimes had a point. That undoubted goal of a “United States of Europe,” on the American model, was not only misguided but always doomed. And she correctly perceived the currency problem. On her very first day at Downing Street in May 1979, she had minuted a memo on the embryonic currency union: “I doubt whether stability can be achieved by a currency system. Indeed it can’t—unless all of the underlying policies of each country are right.” The fate of the euro and the Eurozone have confirmed this, with colossal debt and mass unemployment in Greece, Italy, and Spain. Even so, Thatcher’s manner put her increasingly at odds with her senior colleagues, as well as with European leaders, whom she hectored to their faces and attacked in speeches.

With all this, Herself Alone leads inexorably toward “The fall.” The story has been told before, with the late Alan Watkins’s A Conservative Coup, a valuable contemporary record, but this is the definitive account. In January 1986, Michael Heseltine had stormed out of the Cabinet, after a ferocious conflict, which reflected his strong European commitment. Since then, he had been plotting his revenge, and in November 1990 he challenged her for the party leadership.

Well before that, Thatcher was “getting terribly, terribly tired,” her husband said. She was isolated, angry, and “no longer prepared to argue,” in Butler’s words. “If someone disagreed she didn’t want to know.” In her early days, her adviser John Hoskyns had told her with startling bluntness: “You bully your weaker colleagues. You criticise colleagues in front of each other and in front of their officials. They can’t answer back without appearing disrespectful.” She was only quite insulting to Lawson (although there’s a splendid index entry in Moore’s second volume, “Lawson, Nigel … MT demands haircut for 698”), but she was horrible to Howe. By October 1989, Lawson told Howe, “I’m really reaching the end of my tether. She just doesn’t listen any more,” to which Howe replied, “Nigel, you’ve just got to keep going.” He didn’t, and nor in the end did Howe. His devastating resignation speech on November 13, 1990, delivered in the quietest manner, well-nigh sealed her fate.

Which in smaller respects she herself hastened. Thatcher insisted on appointing Peter Morrison as her last “PPS,” the premier’s parliamentary private secretary or unpaid bag-carrier, and supposedly her liaison officer to the backbench MPs. Morrison was the rich son of peer, a Tory grandee, and grand’s the word: One comical sidelight on that distant age is how often senior Tories were absent at critical moments because they were away pheasant-shooting, Morrison among them. Besides that, one colleague said he “looked as though he was slowly committing suicide” through drink, and when the challenge to Thatcher came, he was too sozzled to concentrate on the task in hand.

She won the first ballot, but the margin was insufficient (a point Morrison hadn’t grasped beforehand), and another would be needed. On a night of intrigue, evasion, and double-dealing, her colleagues came to tell her that if she ran on a second ballot, the dreaded Heseltine would win. And so she withdrew, in a turmoil of rage and bitterness. She barely spoke to some of her colleagues again, but did talk freely of their treachery. Moore flies his Thatcherite colors by endorsing this. In particular, he fingers her successor, John Major, for his disloyalty; he takes as his epigraph “When lovely woman stoops to folly, / And finds too late that men betray,” and he writes of the “unforgettable, tragic spectacle of a woman’s greatness overborne by the littleness of men”—ignoring, as she did herself, the truth that loyalty has to be earned as well as demanded.

Moore paints a sorry portrait of a broken woman in the years after her fall. She wrote (or ghostwriters squeezed out of her) two volumes of memoirs, and she made more money on the American lecture circuit. But she declined mentally, was devastated by Denis’s death, and was then let down by her dysfunctional children, Mark, who barely avoided prison, and Carol, who wrote a distasteful account of her mother’s dementia. And yet Moore is far too lenient in other ways: Lady Thatcher, as she became in 1992, now showed worse judgment than ever, befriending sundry monsters and murderers from around the world. Moore mentions her connection with the bloodstained erstwhile Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet, and Nursultan Nazarbayev, the strongman of Kazakhstan, with whom Tony Blair later had such a lucrative association, but not her friendships with Franjo Tudjman of Croatia and the Chechen leader Aslan Maskhadov. Yes, Thatcher did have some marks of greatness, but littleness as well.

From offstage, she egged on right-wing Tory MPs who strongly opposed Brussels. “In speeches in Chicago and New York in the middle of June [1991], she set out arguments which put the EC in the dock,” Moore writes, which “opened up the prospect of conflict with Major.” This increasing stridency was part of a turn that saw fringe Europhobic parties win nearly a million votes at the 1997 general election (an overlooked factor in the Tory defeat that year), before the rise of the United Kingdom Independence Party, founded only a few years earlier. In the next two decades, UKIP would play on hostility to Europe, and a more widespread concern with immigration, to eat into the Tory base, growing from little more than 3 percent of the popular vote in 2010 to 12.6 percent in 2015, a greater share than the traditional third party, the Liberal Democrats. The threat from UKIP pushed the Conservatives further to the right on Europe, and finally into calling the referendum.

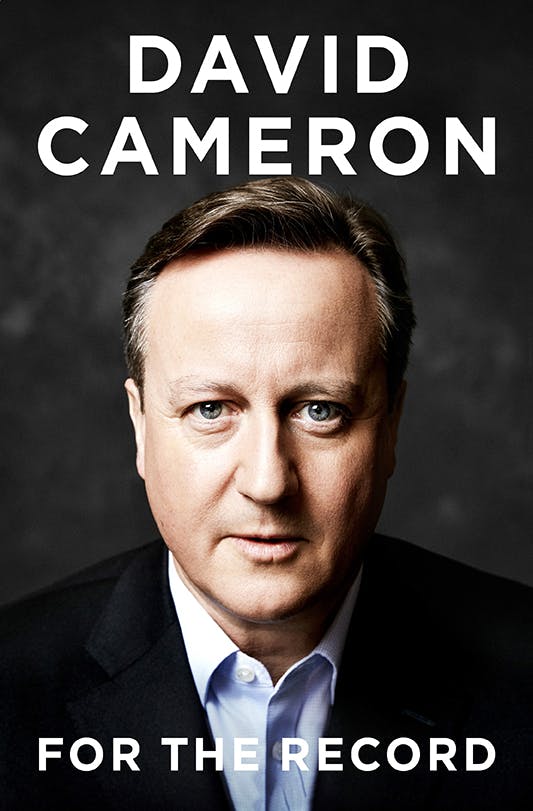

To turn from Thatcher to Cameron is not quite to see history repeating itself as farce, but there’s an essential triviality about Cameron and his career, and now his book. Like him, his memoir has an affable, indolent, Whiggish air, which might have made him an adequate if forgettable prime minister in the eighteenth century. It was his misfortune and ours that he held office at a moment of supreme importance. He tells his own story, from happy country childhood as the son of a well-to-do stockbroker, to effortless passage through Eton and Oxford, then his marriage to Samantha, daughter of Sir Reginald Sheffield, stepdaughter of Lord Astor, and something of an upper-class hippie when they met. Only one dark cloud blots the personal sunshine. In a chapter that can’t have been easy to write and isn’t easy to read, Cameron tells how their son Ivan was born with a severely disabling medical condition and died aged six.

He also recounts his years as a political aide—the word “spad” for “special adviser” litters his text—and as PR man for a dubious television company, before he entered Parliament. Cameron comes clean at last and admits he smoked dope at Eton and later “with Sam’s friends.” As a newly elected MP, he says, he voted for the criminal and catastrophic invasion of Iraq, but “Sam” was passionately opposed. In 2005, he rather surprisingly became Conservative leader, and set about imposing what he says was “my brand of ‘modern, compassionate conservatism.’” Then he says it again—“a modern, compassionate Conservative Party”—and again—“It was a classic compassionate Conservative speech”—and again, and again: In all, the word “compassionate” appears 27 times. He fails to grasp that no one ever voted for the Tories because they were lovable—Thatcher’s electoral triumphs testify to that—and that their selling proposition wasn’t compassion but competence, which Cameron threw away.

His excessively long book takes us over ancient dramas that most people have forgotten, and parades his meager achievements, but he can’t escape from the grim fate we know awaits him, and that he brought on himself: the 2016 referendum on British membership in the European Union. Although Cameron led the campaign for Remain, anyone coming from afar to For the Record might almost think it was the work of a Europhobic Brexiteer, so few good words does he have to say about the EU: “Integration had gone too far,” he laments. “Brussels was too bureaucratic. Britain needed greater protections.” He complains that “we had no hard-and-fast control over immigration as long as we were in the European Union.” And he deplores “yet another treaty that reduced national vetoes and centralised power in Brussels.”

At the same time, “I believed,” he says fatuously, “that in the long term, Turkey ought to be in the European Union,” a belief for which he gives no convincing reason. In reality, there is no serious prospect whatever of Turkey joining the EU, now or “in the long term,” but, by saying that, Cameron opened a space for the Leave campaign to claim in demagogic and xenophobic fashion that hordes of Turkish immigrants would soon descend on England’s green and pleasant land.

Altogether, Cameron reminds us just how feeble his leadership of the Remain side was. Shortly before the vote, he was asked whether he was a “twenty-first–century Neville Chamberlain.” That was “exactly the red rag needed to bring out my bullishness,” he tells us, and so he replied,

In my office I sit two yards away from the Cabinet Room where Winston Churchill decided in May 1940 to fight on against Hitler … he didn’t want to be alone … but he didn’t quit. He didn’t quit on Europe … he didn’t quit on European freedom. We want to fight for these things today, and … You can’t win a football match if you’re not on the pitch.

He calls this his “finest hour of the campaign.” Oh, please.

Like Blair’s gruesome memoir A Journey, this is one more apology that doesn’t apologize. Just as Blair is sorry that things didn’t quite work out as planned in Iraq, but not that he took us into the wretched war in the first place, so Cameron is sorry that he lost the Brexit referendum, but not that he called it. He says over and again that he doesn’t regret holding the referendum. He insists just as often that he didn’t promise a referendum to assuage the rabid Right of his party or UKIP, and that he didn’t assume he would win. And yet, he plainly did act with a complacency bred by the ease with which he became Tory leader and then prime minister, and had then finessed two earlier referendums, one on the voting system and another on Scottish independence.

Above all, Cameron refuses to concede that the very fact of holding the referendum wasn’t just a huge mistake, but—and this is another comparison with Blair and Iraq—was always bound to be, since it could never have had any good outcome. By trying to appease the unappeasable, he was on a hiding to nothing: If the Europhobes had lost, they would simply have come back another time. And Cameron’s underlying claim that a referendum was the only way of clearing the air and uniting the country is as if a Spanish politician in the summer of 1936 had said, “We are a sadly divided nation. Let us clear the air and bring the country together, by fighting a Civil War.”

In a nice line that opened his first volume, Moore wrote, “Socrates famously said that ‘the unexamined life is not worth living.’ He had not, of course, met Margaret Thatcher.” She wasn’t in that respect unique. In his fascinating book Rubber Bullets, the Israeli writer Yaron Ezrahi observed that “autobiography—as the voice of the first person singular, of the self-reflecting, self-narrating individual ... has not flourished in Jewish or Zionist culture.” The memoirs of Israeli leaders “do not address the inner life of their author nor do they provide honest, reflective narrative of the writing, or speaking, self.” No doubt that is so, but he was quite wrong to think of this as a peculiarly Israeli problem. British prime ministerial memoirs, by Attlee, Eden, Macmillan, Thatcher, Blair, and now Cameron, have been a lamentable collection, all devoid of inner life or honest narrative.

Maybe Thatcher had little inner life anyway; for all her intelligence and devotion to work, she certainly had no “hinterland,” as the Labour politician Denis Healey called the wider cultural interests that should sustain someone in public life. And she had absolutely no sense of humor, so that one of the most arduous tasks for her team was inserting jokes into her speeches. In one, they alluded to John Cleese’s “dead parrot” sketch in Monty Python’s Flying Circus, which had become part of Our Island Story. Not only had she never seen Monty Python or heard of the parrot, she still couldn’t understand the joke when it was explained, and asked, “Is it funny?” For that matter, Cameron doesn’t display much of an inner self either. His laid-back or lazy personality, which made him an acute contrast to Thatcher, was reflected in his politics, and now in a memoir free from self-reflection, let alone serious self-criticism about how he dealt with the great issue of his time.

“The issue, of course, is Europe,” said Heseltine when mounting his challenge in 1990. So it has long been, and so it remains. Cameron’s successor, Theresa May, stumbled from one blunder to another, before she called an unnecessary general election in June 2017 and lost her majority, failed to get a Brexit deal through Parliament, and was deposed this summer, to be succeeded by Boris Johnson. He has now managed to precipitate yet another election, after which the Brexit drama may or may not find a conclusion.

One can only look back with bitter regret. If only the British had engaged with Europe in a critical but creative manner, working with sympathetic nations, of which there were quite enough, to preserve the real and great achievements of the European enterprise, while resisting the doomed attempt to create a federal superstate.

Today, Thatcher’s view of Europe “has won much wider acceptance,” says Moore, and he would say that, as someone whose Europhobic journalism has long been distinguished by a kind of genteel fanaticism. But he truly cannot say her view has won universal acceptance in a country where 48 percent voted for Remain. In Britain today, there is no common ground between the sides, no sense of national unity, no democratic agreement to differ—only what Yeats once said of Ireland, “great hatred, little room.” We have managed to reach an outcome that makes no one happy, and is likely to make most people unhappier as time goes by.