In November, the liberal activist and Twitter personality Peter Daou got into a spat with an unlikely adversary: Neera Tanden, the head of the Center for American Progress and Daou’s erstwhile ally in the fight to elect Hillary Clinton president in 2016. After she called his criticism of Obamacare from the left “enraging and the most privileged bs,” Daou tweeted an affronted riposte to his nearly 300,000 followers.

Tanden has since blocked Daou. The clash between these two Clinton loyalists, both of whom spent the 2016 election sparring with supporters of Bernie Sanders online, is illuminating. Tanden runs the most powerful Democratic Party–aligned think tank, where she draws an annual salary of nearly $400,000. Her career and motivations are easy to follow: She’s a paragon of the Democratic establishment, skeptical of the party’s left wing and in a good position to leverage her influence to land a plum spot in a future Democratic administration.

Daou’s motivations are harder to parse. He is one of the very few veterans of the bitterly contentious 2016 Democratic primary to switch sides, transitioning in the past year from one of Clinton’s most fanatical surrogates to an equally fervent booster of Sanders. His change of heart has been startling. This is the same guy who, after Clinton fainted during a visit to the World Trade Center memorial two months before the election, tweeted, “To #Hillary haters jabbering about NYC weather, I LIVE HERE. I usually play outdoor summer hoops and today it was too hot even for a stroll.” (It was 80 degrees and low humidity.) No one, it seemed, was more willing to go all out for Clinton’s lost cause than Daou. It’s no wonder that he got a shout-out in the first section of Clinton’s campaign memoir, What Happened, while Tanden’s name is absent throughout.

But now, Daou’s boundless enthusiasm is redirected. “Only ONE candidate is spearheading a mass movement for systemic change,” Daou tweeted in a characteristic recent outburst. In another, he credited Sanders with having “inspired a new generation of progressive candidates to run for office.” These tweets have been typical of Daou’s feed since April, when he announced his conversion in an essay in The Nation titled “I Was Bernie’s Biggest Critic in 2016—I’ve Changed My Mind.” Daou then began apologizing for his past attacks on Sanders and offered a blanket amnesty to his former critics in the form of mass unblockings.

Some on the left have accused Daou of cynical motives. Sarah Jones, a left-leaning writer at New York magazine (and a former staffer at The New Republic), recently tweeted: “truly embarrassed for everyone enabling Peter Daou’s latest grifter turn.” Others, such as the Mike Gravel teens, have embraced the conversion, hailing Daou as “King!” in reply to his tweets. But the predominant reaction has been one of bemusement. “I can’t gauge how sincere he is, but I support it for entertainment value and because the stakes are so low,” says Alex Nichols, the author of a scathing 2017 profile of Daou in The Outline. “It’s truly puzzling,” says Felix Biederman, a co-host of the popular left-wing podcast Chapo Trap House and a vocal critic of Daou in 2016.

How did Daou get here? He has a wildly unlikely biography, veering from war-torn 1970s Beirut to the dance clubs of 1990s Manhattan to the social media battles of the Trump era. His latest incarnation dovetails with a broader leftward lurch in Democratic politics. But a closer examination of Daou’s life reveals less about the political class’s newfound appreciation for reformist and socialist strains of leftism than it does about the type of personality that finds an appreciative audience in politics—well-meaning, excitable, instinctively loyal, and fundamentally odd.

Peter Daou arrives at 4 p.m. on the dot to an empty sushi bar on the Upper West Side, where we will spend three hours reviewing his entire life (for the last hour, we are joined by his wife, Leela). In person, he is warm and affable, his facial expressions a far cry from the severe grimace in his Twitter profile pic. Since we’re between meals and Daou is a lifelong teetotaler, he orders nothing the whole time. I eventually request a small bottle of hot sake for myself, out of sympathy for the waitstaff.

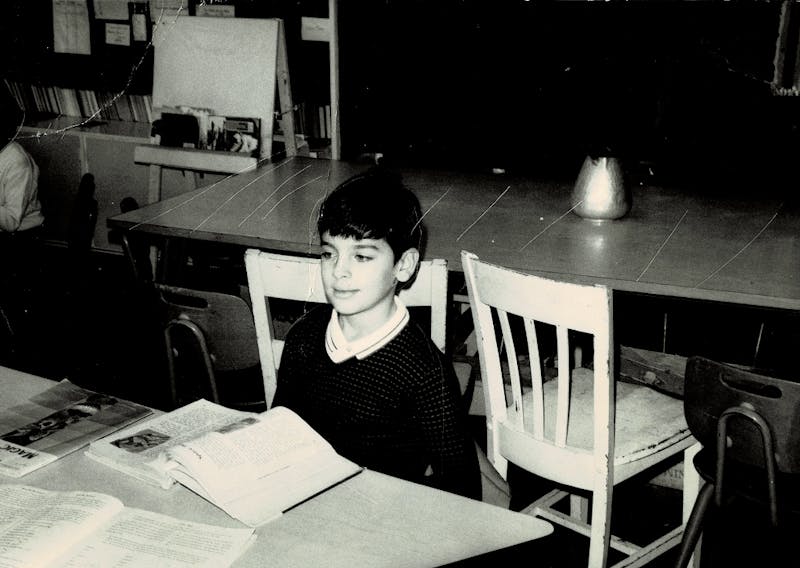

We begin in Beirut, where Daou was born in 1965. He recalls the Lebanese capital of his childhood as a Mediterranean idyll, a jet set–friendly beach town not unlike Miami. His father, Arthur Daou, was a proud Lebanese Christian, while his mother, Suzanna Mann, grew up in a wealthy left-wing Jewish family in New York. They met while Arthur was doing a Ph.D. at Columbia, then moved to Beirut to run a chain of bookstores and raise six children, of whom Peter was the second-oldest.

Daou had a cultured upbringing, learning classical and modern Arabic in addition to English and French, reading poetry, hiking past ancient ruins, playing jazz piano, and taking regular trips to New York to visit his relatives. His mother is the sister of the writer Erica Jong, whose bestselling 1973 semi-autobiographical novel, Fear of Flying, was an early, enormously influential work of sex-positive feminism. It includes a chapter where the narrator visits her sister in Beirut and is subjected to a graphically detailed, cringingly orientalist seduction attempt by her Lebanese brother-in-law “Pierre,” a stand-in for Arthur. (“It’s completely made up,” Jong tells me.)

“It caused a lot of consternation and a lot of pain to my mother, but that’s been aired publicly,” says Daou. “I don’t need my aunt in America to tell me who my Lebanese father was. He was a highly intelligent man, an intense human being. And he had an exceptionally difficult life.”

Daou’s Edenic childhood came to an end in 1975, the start of Lebanon’s 15-year civil war, pitting the Western-backed, Christian-dominated Lebanese government against Soviet-backed Muslim insurgents. Beirut would see some of the worst urban guerrilla fighting in modern history, and Daou’s adolescence was one of constant, terrifying violence. His balcony overlooked a hospital, from where, he says, he would “watch these mangled bodies trailing blood being thrown on the backs of jeeps and taken to the emergency room.”

“I remember times where it was a rocket every few seconds, and we literally would sit in hallways or bunkers, just counting the seconds,” Daou says. His memories of those years include collecting shrapnel, dodging sniper fire to buy bread, and learning that his best friend had been grazed by bullets. Multiple times, the Daous fled Beirut, first to Paris and then to New York, but Arthur would insist on returning whenever there was a lull in the fighting.

In 1982, the armed wing of the Phalange, a right-wing Lebanese Christian party backed by Israel, massacred hundreds of Palestinian civilians in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps in West Beirut, provoking international outrage. More than three decades later, some of Daou’s online critics would imply he participated in these mass killings at age 17—a charge for which there is zero evidence, and which he calls “one of the most hideous things that has ever been lobbed at me in my life.”

What is true is that, starting in his mid-teens, Daou was forced to undergo basic training in the militia of the Lebanese Forces, a rival Christian party, and spent hours after school each day for several years learning how to fire a rifle or take cover from a grenade. Although Daou frequently brings up his military experience online—much of the controversy around this stems from a 2014 tweet, in which he cited being “in the Christian militia trained by [Israel Defense Forces]” to shut down a right-wing critic—he never deployed, and only ever experienced combat as a civilian. “I remember one training where I sliced my hand really badly on a piece of glass, and there literally was a gash in my hand, just bleeding,” Daou says. “So I go up to the trainer … and I said, look at this. He said, ‘Oh really, you’re upset about that? I want you to do 50 pushups on that hand in the mud.’”

Daou’s memory of his militia years has an essentially apolitical flavor. He condemns all massacres and human rights violations, and, in hindsight, has no discernible factional loyalty. In 2016, he detailed his experiences in a blog post. Of the civil war, he wrote, “It was evil made manifest and I still can’t believe my family and I survived it in one piece. It causes me profound sadness that so many of my fellow Lebanese, Christian and Muslim, were not so fortunate.”

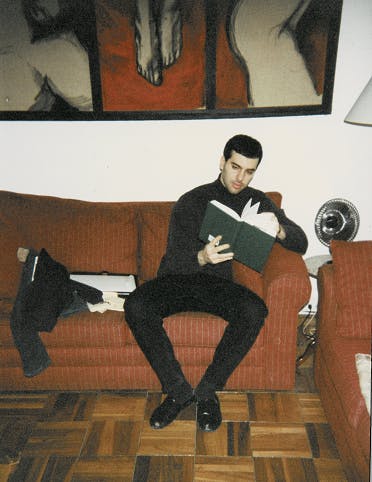

In 1984, Daou left Lebanon permanently for New York. He enrolled at NYU and supported himself by working odd jobs, like bartending at a Greenwich Village haunt whose regulars included Andy Warhol and Grace Jones. A talented musician since childhood, Daou became a mainstay at jazz clubs. In the late 1980s, he met a group of D.J.s at a small record company called Nu Groove, a hub of the electronic dance music scene then spreading from Chicago to New York. They hired Daou to play jazz piano on a track, and so began a decade-long career of considerable success in the recording industry, during which Daou played keyboards on remixes for musicians like Björk, Miles Davis, and Mariah Carey.

In 1994, he produced a hit dance record featuring his then-wife, Vanessa, singing erotic lyrics taken from the poetry of Erica Jong. The album drew its name, Zipless, from Jong’s famous coinage “the zipless fuck” (a no-strings-attached hookup), featured in the same novel in which Jong essentially depicts Daou’s father trying to force her to perform oral sex.

Throughout the 1990s, Daou had VIP access at Manhattan’s hottest dance clubs, where he would hang out with stars like Moby, Elton John, Puff Daddy, and the Edge. He was completely sober the whole time. “I would get high on the music,” he says.

While Daou describes himself in this era as “the typical cliché, the bleeding heart New Yorker,” politics wasn’t a central part of his life. That changed in 2000, when Napster ruined the music industry and George W. Bush stole the presidency. Daou was troubled enough by the latter to immerse himself in the world of progressive blogging, joining the nascent Netroots movement of activists organizing against Bush. After 9/11, he became a dedicated anti-war protester, demonstrating against the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. “I’d grown up in a war, and I knew what a war could do,” he says. He also began writing constantly, and his blog, the Daou Report, got picked up by Salon.

While much of the progressive Netroots crowd embraced Howard Dean, the anti-war insurgent of the 2004 primaries, Daou was drawn to the establishment-approved eventual nominee who was famously for the war before he was against it. “I found John Kerry interesting because he had volunteered to go to Vietnam,” Daou says. “Because of my war experience, I thought, OK, who would volunteer to go to war if they didn’t really care about their country?” Daou drafted a 15-page memo on building a digital strategy to appeal to the Netroots, brought it to a Hamptons fundraiser, and handed it to Kerry. The next day, he was hired, and he was in the Kerry campaign’s war room when Bush was reelected that November.

The following month, Daou and fellow Kerry campaign survivor James Boyce were among three dozen people who attended a meeting at Arianna Huffington’s home in Los Angeles to help brainstorm a progressive alternative to the right-wing Drudge Report. In May 2005, Huffington launched the Huffington Post, co-founded with venture capitalist Ken Lerer, Jonah Peretti (who later founded BuzzFeed), and the late Andrew Breitbart (who later founded an eponymous right-wing hate site). In 2010, Daou and Boyce sued Huffington and Lerer for allegedly stealing the idea for the Huffington Post, by then valued at over $300 million, from their proposed 1460 Memorandum (referring to the number of days between presidential elections, excluding Leap Day). Larry David, an investor in the Huffington Post, told Vanity Fair of their proposal: “All I remember is Arianna telling me about this on a number of occasions and feeling sorry for her because I thought it was such a terrible idea.”

The suit was settled in 2014 for an undisclosed sum. Daou expressed satisfaction with the result and pledged to establish “the Daou Foundation (daoufoundation.org) to provide grants to young women activists and entrepreneurs who are using social media and technology to change our world for the better.” (The website for the Daou Foundation currently includes a donation link for Planned Parenthood, the full text of the Communist Manifesto, and nothing else.) Daou declines to go into any detail about the lawsuit, beyond noting the existence of public court records. “After it was settled, we hugged, and I felt like it was OK,” he says.

In 2006, Daou met with then-Senator Hillary Clinton, and their conversation, originally scheduled for 15 minutes, sprawled over an hour. A fateful friendship was born, and Daou has remained loyal to Clinton ever since. “I come from a Lebanese culture—honor, loyalty, dignity,” he says. “These things are valued differently. More priority is put on loyalty, especially having come out of a war. You’re in the trenches, they have flaws, everybody has flaws.”

Daou was soon brought on to run Clinton’s 2008 digital team, which had the misfortune to confront Barack Obama’s groundbreaking campaign. “Those guys were monsters,” Daou says. “And I could not compete with them. I did everything I could.” According to an email from a Clinton staffer released by WikiLeaks in 2016, Daou “apparently burned a lot of bridges [in 2008] ... digital folks from that campaign do not speak highly of him.”

While Daou welcomed Obama’s victory against John McCain, he quickly grew disenchanted with the Obama presidency, and publicly criticized its national security policies. “I thought, OK, we’re going to overturn everything Bush did,” he says. “And then, wait a minute, why is Gitmo still open? We’re still droning babies? Now we’re assassinating a U.S. citizen? And then I thought, this isn’t going quite as hopey-changey as some people think.”

Daou spent the Obama years blogging and consulting. “I’ve never sought the money,” he says. “Somebody more scheming or crafty probably could have parlayed two presidential campaigns into a very lucrative life, working for big corporations. That’s not what I wanted to do. I wanted to change the world.”

While he never formally worked for the Clinton 2016 campaign, Daou did accept an invitation from Clinton’s longtime media guru David Brock to run a website called Blue Nation Review, which Daou renamed Shareblue. The initial concept was to go after Republicans in defense of Clinton, but Shareblue soon turned its fire on Sanders, which Daou says he regrets.

It was altogether a painful year for Daou and his second wife, Leela, whom he met in 2012 at a jazz club. “All her friends are Bernie supporters, and she would have been had she not married me,” he says, and she confirms. Besides his highly visible Twitter fights, they both also faced harassment, including rape and death threats, from what they’ve determined were Russian trolls on social media. In the midst of all that, the Daous lost their first child due to an ectopic pregnancy. Oh, and Trump won.

“All you could do is just take it one moment at a time,” Leela says. “Peter’s so incredible, his name means ‘rock,’ and he truly embodies that. He’s a wonderful man.”

In June 2017, Leela began creating memes with fact-checked quotes, each with a unique verification code, as a way to counter the spread of disinformation online. What ultimately became the website Verrit “started very innocently,” she says. “It was a small project. I ran it for a few months, and it really didn’t get that much attention.” That all started to change in August, when Daou got a call from Clinton. “She thanked me for all the hard work I did, and she let me know that I was quoted in her book,” he recalls. “And then she asked, ‘What are you working on, Peter?’” He told her about Verrit, and she said she’d like to help. Not long after, she tweeted about it, prompting what Daou calls “one of the wildest days of my life.” Besides being roundly mocked on Twitter for being a ham-fisted, pro-Clinton propaganda tool, the website itself immediately crashed. (Daou claims this was due to a DDoS attack originating in Ukraine.)

Daou freely admits that Verrit was a spectacular failure, in part because Clinton promoted the site before it was ready for mass consumption. “It all just went wrong. And now we laugh about it; we’ll joke, we’ll answer people with Verrit codes,” he says.

“Politico wrote a piece about it, and then that Outline piece came out—it was a pile-on of epic proportions,” he adds. Daou acknowledges that Verrit should have stuck to fact-checking instead of defending Clinton’s legacy. Soon the project was abandoned. “It just didn’t seem worth it at that point because it was so panned that no matter what we did, we were not going to be able to salvage it,” Leela says. “People didn’t understand our earnestness.”

The words “earnest” and “sincere” come up a lot in our discussion and in subsequent interviews with Daou’s family. “Peter is an incredibly earnest man,” says Leela. “He’s very genuine, and it’s difficult to really express that on social media. Everybody’s very cynical.”

The writer Molly Jong-Fast—Erica Jong’s daughter, Daou’s cousin, and a Twitter personality in her own right—echoes this sentiment. “People are sometimes irritated with his earnestness, but I like it,” she says when I note some leftists question Daou’s motivations. “I don’t quite understand how he would benefit,” she adds. “He’s very sincere, he really likes Bernie.”

“I think he’s completely sincere,” says Erica Jong.

“I’m a very earnest person,” says Daou. “The idealism of being a Lebanese kid who came here and survived the war and made it? That never leaves. I just want to do good ... but it does come off as earnest.”

Daou has a book to promote—Digital Civil War: Confronting the Far-Right Menace, which he only mentions when prompted—but aside from that, there’s no obvious way he’s cashing in on the Sanders campaign. “I wrote a book last year, and it came out in April, but I’m not selling anything,” Daou says. “You don’t grift to the left, you grift to the right or the center, you grift to the corporations. A guy like me, if I wanted to grift, you go do major corporate work—$100,000 a month and you’re just wallowing in the mud.”

Besides boosting Sanders on Twitter, the Daous have begun supporting progressive primary challengers against incumbent congressional Democrats, from New York (they are currently paid advisers to Lindsey Boylan, who is challenging Representative Jerry Nadler, as well as Lauren Ashcraft, the democratic socialist running against Representative Carolyn Maloney) to San Francisco (they support Shahid Buttar, the democratic socialist in a long-shot bid against Speaker Nancy Pelosi). They seem to subscribe to the Sandersian notion that Clinton’s risk-averse establishment politics doomed the Democrats in 2016 and that bold, revolutionary politics is the antidote. And while they may not be chasing big money, they have found a new fan base. “Right now, the way we’ve been welcomed and the way this community is, we’re at home, and we’re staying,” says Peter. “Honestly, it’s been moving,” adds Leela. “I’ve had people say, ‘Sorry we attacked you in 2016.’”

In Daou’s view, there’s no ideological inconsistency in the campaigns or causes he has championed. He always disagreed with Clinton on the Iraq War, drones, fracking, and more, but until recently, he had “a very binary view of Democrats and Republicans. Democrats were the good party, Republicans, the bad party.... It was extremely black and white thinking.” He adds, “I’m late to politics, I’m late to learning about socialism and capitalism and systemic issues and neoliberalism. I never learned those things.” Daou maintains that he’s the same progressive he’s always been on the issues, but that he’s been radicalized in terms of his understanding of the political process and what it will take to effect change.

Despite his professed personal loyalty, Daou hasn’t communicated with Clinton in the past two years since she tweeted about Verrit. “I had a couple of interactions with some of her aides who I worked with in the past, and not very pleasant ones,” he says, citing Clinton consiglieres Jennifer Palmieri and Nick Merrill. But, he insists, “I don’t need ego boosts. If Team Clinton thinks I’m an outsider now, so be it.”

Faiz Shakir, Sanders’s 2020 campaign manager and a Netroots veteran, is grateful for Daou’s support. “We’ve both been involved in progressive movement-building for years,” Shakir says. “And one of the rules of movement-building is to ensure you are welcoming, so that you’re growing and winning. I very much welcome Peter’s advocacy this year to help us grow the movement for Bernie’s agenda.” Polls show that the 78-year-old Sanders is a viable candidate, but hardly the safe bet that Clinton was last time. If Daou is betting his career on a Sanders victory next year, he’s taking a significant risk.

Still, Daou’s conversion has gotten a bit of a media rollout. In the past week, he’s appeared on the Sanders campaign podcast, written an op-ed for Medium, and granted an interview to Politico. While it was my idea to reach out to Daou for this profile, I am cognizant that this article is now a part of that rollout.

What is a grifter, anyway? Traditionally, the term refers to con artists who earn money through illicit methods. Nowadays, it’s deployed against anyone with a large social media following who is palpably thirsty for attention and clout. The assumption is that Twitter followers represent a form of social capital that can eventually be exchanged for actual capital. But what if cashing in is beside the point? What if politics, a grifty business where everybody is greedy for power and the spotlight, needs people like Daou to smooth over the hypocrisies that lie at its heart?

“I’m not ashamed of anything I’ve done in my life,” Daou tells me. “It’s all been part of this crazy journey. I’ve done the best I can every step of the way.”