The Upswing, Robert Putnam and Shaylyn Romney Garrett’s ambitious new study of American Progressivism found and lost, opens with a disturbing vision. If Alexis de Tocqueville, who chronicled the flowering of American democracy in the 1830s, were transported into the present, the authors imagine, this is what he would see: an inordinate and grotesque segregation of the population by class; an economy ruled by corporate monopolies, gaining ever-greater power through mergers and acquisitions; workers powerless to negotiate for themselves amid the suppression of labor unions; and reckless corporate managers whose only aim is to make money for their shareholders, acting with little or no regard for any public interest. He would see the transmutation of corporate financial power into inordinate political power, undermining the machinery of democracy and leading to a pervading disillusionment among the citizenry.

Much as Virgil was for Dante in the Inferno, Tocqueville serves as Putnam and Garrett’s guide through the hell of contemporary American social, economic, and political life. He would perceive the ideology of extreme individualism and pure self-interest in, for instance, the irresponsible energy policy that is propelling the country toward an ecological crisis of disastrous proportions. He would weep as he traveled throughout the land and discovered a population in the throes of widespread drug usage, alcohol abuse, and suffering through a plague of what the economists Angus Deaton and Anne Case have called “deaths of despair.” Above all, he would observe the evaporation of the public-mindedness he had hailed as America’s saving grace in the 1830s.

When Tocqueville, whom Putnam has called “the patron saint of American communitarians,” traveled from his native France to the United States in 1831, he was struck by the propensity of Americans to form multiple, overlapping private associations. These private associations were one of the pillars of the American system of government, he argued in his classic study Democracy in America. They provided a buffer between citizens and their government (hence, contemporary social scientists have dubbed them “intermediary associations”). Voluntary associations also helped citizens develop the skills of deliberation, mutual trust, and debate that allowed them to function effectively in the political world. In Tocqueville’s view, these social groupings served to balance the extremely individualistic nature of the American character, creating an integrated political perspective he called “self-interest rightly understood.” He found Americans of the time keenly interested in and well informed about political issues, unlike most Americans of today.

The disappearance of these virtues from society, Putnam and Garrett point out, is not without precedent. There is a conceit hidden within their lengthy opening survey of inequalities: It is a portrait not only of America today, but also of America in the Gilded Age at the end of the nineteenth century, another period of our history marked by extreme disparities of wealth and widespread social and political unrest. We have succeeded, the writers are demonstrating, in creating a new Gilded Age. The problems that we face today are the same challenges that confronted the first era of Progressive reform more than a century ago.

Between the first Gilded Age and ours, The Upswing proposes, there was a lengthy period—almost three-quarters of a century—in which these trends were headed in the opposite direction. This positive momentum of social change was set in motion by the Progressive movement of the first two decades of the twentieth century—a striking legacy of reform that is largely overlooked in standard historical analysis. What’s more, if the first Progressives of the early twentieth century could reverse the course of history as they did, the authors contend, we of the early twenty-first century can do the same. That is the message they wish to impart to Americans of today, and to those of us who count ourselves on the American left. We have the capability to re-create an American civic community.

Robert Putnam, a professor of public policy at Harvard, has spent much of his career studying how and why people form voluntary associations—and how they drift away from them—in the course of modern life. He is best known for his 2000 book, Bowling Alone, which described and analyzed the downfall of private community institutions in America in recent decades. He went on to chart the ongoing impact of this sense of isolation and fracture in his 2015 study, Our Kids, which took stock of the corrosive forces of industrial and civic decline in his hometown of Port Clinton, Ohio. Those books popularized the term “social capital,” the idea that the creation of norms of trust and reciprocity in a society requires social networks in which people interact cooperatively and productively with one another on an ongoing basis.

But his intellectual breakthrough was his 1993 study, Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. In the early 1970s, the Italian government began to devolve many of its powers down to the local level; Putnam, who was studying in Rome at the time, saw an unparalleled experiment unfolding before him. Over the next decades, working with two Italian researchers, he sought to determine which parts of Italy were adapting best to the new challenge. What they found was a marked contrast between northern and southern Italy: Briefly, they determined that political systems in the south were vertical in nature—extremely top-down—whereas Italian cities in the north distributed power more horizontally—which is also to say, much more democratically.

Putnam called the arrangements he found in northern Italy the “civic community.” The civic community was built on a foundation of four outstanding qualities: citizen engagement, that is, the active involvement by average citizens in the political life of their community; political equality, entailing equal access to the political process, along with commensurate community obligations; high levels of trust, solidarity, and tolerance among citizens; and a rich associational life, creating what he called “structures of cooperation.” The civic community, however, need not be a unitary entity, Putnam found; members of such a community could be just as divided ideologically over political issues as they were in any other region of the country. What distinguished the civic community was that its members were willing to compromise their ideological differences for the sake of the public good.

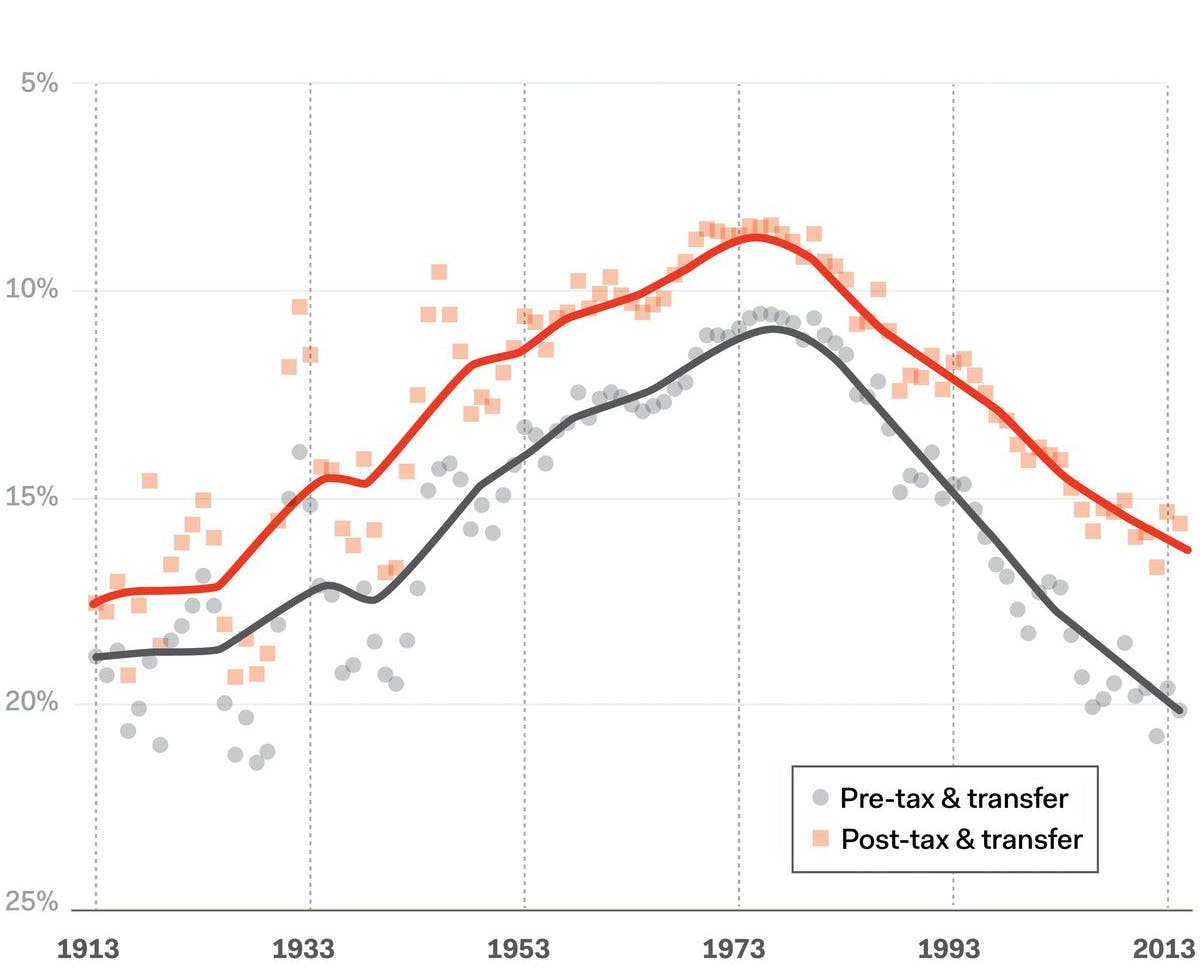

In The Upswing, Putnam and Garrett apply the same mode of analysis to a period in the history of the United States, searching for the features of public life that enable—or constrain—the functioning of democracy. The first six and half decades or so of the twentieth century, they tell us, were characterized by a significant increase in economic equality, a rough rapprochement between the two major political parties, a sense of solidarity—a “we are all in this together” spirit—and a culture of community rather than selfish individualism. Even in the fraught areas of racial and gender equality, they unearth evidence of significant advancement. After 1970, in their analysis, all of these trends reversed direction. The whole pattern is represented graphically by what the authors call the upside-down U-curve, which they also label an “I-We-I” curve, signifying the transition from the self-centered society of the late nineteenth century to a communitarian one, and then an abrupt reversal of this course. The first part of the curve, from approximately 1900 to 1970, constitutes the “Upswing” of the book’s title.

Putnam and Garrett are rewriting the political history of the twentieth century here. In most accounts, the New Deal is considered the point at which the United States began to be transformed into the liberal society it was until Ronald Reagan took office. Putnam and Garrett insist that this is not quite right: The New Deal may have revived and fortified the culture of community-oriented politics of the Progressive era after a “pause” (not a reversal) during the 1920s, and the solidarity developed during World War II reinforced this trend, but it was the Progressives who redirected America’s course toward a more ideologically liberal consensus.

In this telling, the long-lasting accomplishments of the Progressive era considerably overshadow those of the New Deal. Progressive reformers passed four constitutional amendments. Three of these amendments were of great political consequence: They established the constitutionality of a progressive income tax, mandated the direct election of U.S. senators, and—at long last—gave the franchise to women. Absent the Sixteenth Amendment, Franklin D. Roosevelt could not have created the progressive tax system he needed to finance the New Deal and World War II. (The authors have little to say about the Eighteenth Amendment allowing Congress to ban alcohol sales in the United States, except that it was a “greater incursion on individual liberty than most Americans expected it to be.”)

Other political reforms the Progressives effected included banning corporations from contributing any of their funds to federal election campaigns (a law rendered moot a century later by the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United decision); the Australian (secret) ballot; and the initiative, referendum, and recall systems at the state level. The purpose of all these reforms was to wrest power from the grip of a domineering economic elite and place it in the hands of regular citizens.

Using civil service reform, the Progressives brought a modern administrative state into being, putting an end to the corrupt spoils systems dating from the 1830s. A key part of this shift was the establishment of regulatory bodies to oversee the new corporate behemoths of the industrial age. Progressive legislators enacted protective labor laws, minimum wage and workers’ compensation measures, and antitrust statutes, as well as achieving food and drug regulation, protection of natural resources and public lands, and creating a vast system of playgrounds, public parks, and libraries.

But their greatest achievements may lie in the field of education. Progressives invented the institution of kindergarten in America, succeeded in making high school education universal and free, increased college enrollment, championed the German model of the research university, and sponsored the first serious vocational education programs in schools in the United States. Under the leadership of Governor Robert La Follette, professors at the University of Wisconsin pioneered the application of social science research to the making of public policy. Later generations of policymakers would reap the results of this: The core of the social security plan later adopted and put into effect by FDR was developed at the University of Wisconsin during the Progressive years.

Putnam and Garrett see a direct link between improvements in educational achievement and advancements in technology, and attribute America’s phenomenal rate of economic growth in the middle decades of the twentieth century to the educational reforms of the Progressive era. Progressives were not just idealistic do-gooders. They created the foundation of the modern American economy. By the 1960s, levels of inequality in the United States had reached historic lows. The authors see the inaugural address of John F. Kennedy in 1961 as a high point for civic-mindedness in American democracy, encapsulated in his exhortation that Americans should “ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country.” Yet in this moment of triumph, they see the beginnings of an unraveling:

JFK had foreshadowed the transformation that was to come, because his idealistic rhetoric was, in retrospect, proclaimed from a summit to which we had painstakingly climbed, but were about to tumble right back down. And though that summit was not nearly as high as America could hope to climb toward equality and inclusion, it was closer than we had yet come to enacting the Founders’ vision of “one nation ... with liberty and justice for all.”

The work of building the civic community was far from complete, and it would not be long before it began to come undone.

Just as Putnam and Garrett identify an upswing, they also trace a decline beginning in the 1970s. For this, too, they offer an explanation that departs from the standard historical narrative, suggesting that it was not Ronald Reagan who brought the long period of liberal rule to an abrupt halt, but rather the baby-boomers of the 1960s who, turning from the communitarian idealism of the early part of the decade toward a more self-oriented direction, set off a chain reaction that ended up blowing the whole Progressive-liberal order to smithereens.

For each of four major areas of American life in the twentieth century that the authors explore in detail—economics, politics, society, and culture—they set up a pair of opposites in the chapter title. In the chapter on economics, they examine “The Rise and Fall of Equality.” They classify the period of rising the Great Convergence, and the period of falling equality the Great Divergence—a reversion to the acute inequality of the last decades of the nineteenth century. The Great Convergence was the result of policies initiated during the Progressive era and the New Deal, such as progressive taxation, strict financial regulation, a living minimum wage, adequate spending for a social safety net, and promoting unionization of the workforce. And the Great Divergence—a term that New Republic columnist Timothy Noah took as the title of his definitive treatment of the subject in 2012—has come about as the result of a deliberate reversal, since the 1960s, of every single one of these public policy approaches.

At the end of this chapter, Putnam and Garrett speculate on the power of shifting social norms to prompt these swings in economic equality. They see a prime example of normative change in two generations of the Romney family: George Romney, the chairman and CEO of American Motors in the 1950s, habitually turned down substantial pay raises and bonuses because he didn’t want to set a bad example of greed for other employees of the company. A generation later, his son Mitt, at the helm of the private equity firm Bain Capital, evinced a very different attitude toward executive compensation, and expressed disdain for the 47 percent of the American people whom he considers freeloaders, reliant on the types of government benefits his father, as governor of Michigan and Republican presidential candidate, supported.

The chapter on politics takes us “From Tribalism to Comity and Back Again.” The Progressive era inaugurated a period of accommodation between the two major American political parties that derived, initially, from the fact that they both contained strong Progressive elements. Well into the middle of the century, Thomas Dewey, the failed Republican candidate of 1948, could remark that “the resemblance between the parties and the similarities which their party platforms show are the very heart of the strength of the American political system.” Once the parties split over race in the 1960s, the divide between them widened, until it included virtually every other political issue in American politics as well. Polarization that had begun at the elite level filtered down to that of the ordinary citizen, creating the bitter and seemingly irreconcilable cleavages in American society we are confronting today.

The Progressive era had created an “intensely Tocquevillian America.” It spawned a stunning array of voluntary associations from the NAACP to the Boy Scouts and the Girl Scouts, the Audubon Society, the service clubs, and the PTA. The book’s chapter on society tracks the decline of a great number of these civic groups since the 1960s, when they saw a decrease in their active membership. Putnam and Garrett add that the decline of serious religious engagement in America in recent years has been a blow to American civil society, since regular churchgoers volunteer for secular causes at two or three times the rate of other citizens. American philanthropy also declined significantly in this period, except at the very top, where tycoons like Bill Gates, in contrast to the billionaire philanthropists of the industrial age, insist on overseeing their foundations themselves.

Putnam and Garrett lament most of all the precipitous decline of labor unions since 1970. Unions, they emphasize, at the peak of their influence, were social institutions as well as bargaining mechanisms. They embody the ethic of solidarity, and they spread it beyond the workplace through society at large. Solidarity is one of the norms most essential to maintenance of a civic community, and the weakening of that norm undermines the social trust that makes such a community feasible.

The discussion of the role of culture in mediating all these sea changes in American public life is perhaps the most suggestive element of Putnam and Garrett’s analysis. The authors well understand that culture is not a static entity, like a finished painting that will never change; it is, they tell us, borrowing a concept from the literary critic Lionel Trilling, “a contest, a dialectic, a struggle.” The struggle throughout American history has been one between self-interest and social obligation, with the pendulum swinging from one to the other and back over the last 120 years. Putnam has used Ngram analysis to chart these back-and-forth changes scientifically. Ngram analysis is a method of tracking the frequency with which a word or a set of words is used in printed texts over a period of time, drawing on books digitized by Google. From 1900 to 1965, Ngram analysis has shown, the word “We” predominated strongly over the word “I.” After 1965, that relationship reversed, with the frequency of the word “I” nearly doubling between 1965 and 2008. Hence the “I-We-I” century.

Ngram analysis also shows that the most essential concepts of the Progressive age—“association” (or “associationism”) and “cooperation,” both expressive of communitarian ideals—were two of the most popular terms in American writing during the first two-thirds of the twentieth century, but circa 1970 their usage began tapering off. (The word “socialism” was included in the analysis but had a relatively low level of popularity among Americans in both eras.)

What is the relationship of the four variables of economics, politics, society, and culture to one another? It is almost impossible to chart a chain of causation, the authors say, because all the birds in this flock suddenly changed direction at exactly the same time. They do indicate, however, that there is a “modest tendency for economic inequality, especially wealth inequality, to lag” behind changes in politics, society, and culture. “Economic inequality,” Putnam and Garrett propose, is “slightly more likely to be the caboose of social change than the engine.”

That suggestion offers a corrective to the Marxist theory that changes in economic relations drive history. Putnam and Garrett take a direct swipe at Marx’s worldview when they say that “bits of evidence seem to suggest that cultural change might have led the way, contrary to the common belief (perhaps derived from Marxism) that culture is merely froth on the waves of socioeconomic change.” They are more attracted to Max Weber’s idea that culture sometimes leads, and sometimes reinforces, the historical process underway at the time. Weber recognized that humans are driven by material interests. But he also speculated that culture could function like the switches on a railroad track. “Not ideas, but material and ideal interests directly govern men’s conduct,” he wrote. “Yet very frequently the ‘world-images’ that have been created by ‘ideas’ have, like switchmen, determined the tracks along which action has been pushed by the dynamics of interest.”

The authors treat the experiences of African Americans and women in twentieth-century America as subjects separate from the broad areas of politics, economics, society, and culture, since the statistical information for these two groups does not fit quite as neatly into the upside-down U-curve as it does for white men. However, the general pattern for these groups is still similar, with indications of real improvement in their lives over the first six decades of the century, followed by a noticeable drop-off beginning at the 1970 point, particularly dramatic in the case of African Americans.

Putnam and Garrett are at pains to dispel two myths. The first involves the misconception—perhaps especially common among white Americans—that the Black civil rights movement started around the mid-1950s, and culminated in a stunning burst of progress in the first half of the succeeding decade. Putnam and Garrett instead focus on what they call the Long Civil Rights Movement, which dates to the first decades of the twentieth century. The 1909 founding of the NAACP by W.E.B. Du Bois and others might be taken as its starting point. One reason that the Long Civil Rights Movement has received short shrift in standard historical accounts, Putnam and Garrett suggest, is that the signal progress it achieved came at the hands of Black Americans themselves, very much in opposition to the prevailing white political establishment. The Great Migration of Black Americans from the Jim Crow South into the North set the stage for this steady drive toward greater equality in the spheres of health, education, political activity, and economic outcomes.

The white backlash to the great legislative victories of the early and mid-1960s was a key reason why the steep plummeting of the U-curve after the 1960s was especially devastating for Black Americans. White racial resentments were most acute in the states of the former Confederacy, but also took hold in the North, with George Wallace’s proto-Trumpian presidential run in 1968 garnering surprisingly robust support in many Northern precincts.

With respect to the struggle of American women for equal status, the authors challenge the first wave–second wave interpretation of twentieth-century feminism, which views the interval between the attainment of the right to vote in 1920 and the sudden resuscitation of feminist organizing in the late 1960s and early 1970s as a period of near-complete stagnation. They show that this four-decade stretch included substantial progress for women in education (with marked increases in graduation rates in both high school and college) and in the workforce (albeit in relatively underpaid positions in fields segregated by gender). It took longer for women to gain significant entry into graduate programs and professional schools—and longer still for them to ascend to political leadership in appreciable numbers.

The authors raise the question of whether African Americans and women were incorporated into the American “We” over this period of time, and their answer is a qualified yes—they were, but to a significantly lesser degree. The collapse of the upward trend in economic equality starting around 1970 did not greatly affect middle- and upper-class white women, but it has been injurious to the entire population of working-class Americans, including working-class women.

So exactly what happened in the ’60s to turn the tide away from a longstanding communitarian ethos generated by the Progressives that had endured for 60 to 70 years, toward a mean and self-centered one? To begin with, the 1950s happened. This was a decade when Tocqueville’s ideal balance between individual liberty and communal solidarity tipped too far in the direction of the latter, producing an atmosphere of stifling conformity. “Conformity is the dark twin of community,” the authors write, “for communitarianism almost by definition involves pressure to conform to norms.” A growing rebellion against such pressure was manifested in many of the bestsellers of the period—books like The Organization Man, The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit, Individualism Reconsidered, and The Lonely Crowd. The classic youth film of the era was Rebel Without a Cause; its defining novel, the disaffected The Catcher in the Rye.

The 1960s, by contrast, was a decade of intense politics, and Putnam and Garrett recount the emergence of strong individualistic tendencies in both the New Right and the New Left. Among members of the New Right, the works of Ayn Rand became oracular. Rand took libertarian philosophy to the most extreme point, preaching the virtues of selfishness and the evils of charity, asserting that “Altruism is incompatible with freedom, with capitalism, and with individual rights.” The New Left at the opening of the decade seemed headed in a communitarian direction. The legendary Port Huron Statement of 1962, which launched the Students for a Democratic Society, advocated participatory democracy and condemned “egoistic individualism.” SDS was at the center of what came to be called the Movement, but after 1965 the Movement began to splinter, with former members heading off on their own individual quests.

While the Movement sank into oblivion, the hippie counterculture—with slogans like “Do your own thing”—gained the upper hand. The major political heritage from the 1960s, for liberals, has been a passionate involvement with individual rights, and this has been, in the opinion of the authors, a double-edged sword. On the one hand, the emphasis on the individual has fueled efforts for marginalized groups to gain the due rights of American citizenship, especially the right to be treated as equals before the law. On the other hand, the intensive and almost exclusive focus on rights has shunted aside nearly all concerns relating to community. Following the critique pioneered by the historian Christopher Lasch, Putnam and Garrett note that the cultural aftermath of the ’60s was a period of prolonged narcissism—a sensibility that very much persists into the age of Trump.

The authors call the 1960s “the hinge of the twentieth century” and, in a section titled “Concatenated Crises,” list the various upheavals the advance guard of the baby-boomers experienced. What stands out is the near-omnipresence of violence during this period: the assassination of President John F. Kennedy early in the decade; the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy toward its end; the war in Vietnam, which started in the first half of 1965 and continued unabated to 1974; a series of urban riots that began in the summer of 1965 and continued for four successive summers; frequent violent protests, including the all-out confrontations between demonstrators and police and National Guard troops at the 1968 Democratic Convention; the bombings by the Weathermen that commenced in the last year of the decade; and the brutal, bizarre Manson family murders that took place that last summer of the decade, which many saw as a symbolic and even inevitable culmination to a decade of seemingly endless traumatic violence.

Putnam and Garrett suggest that the synergy between all these events produced something like “a national nervous breakdown ... the ultimate perfect storm,” and it certainly did, but the storm was not over yet. When these boomers entered the 1970s, they were subjected to a series of bewildering economic shocks, including the Arab oil embargo of 1973 and the unprecedented combination of increasing inflation and high unemployment called stagflation, charted regularly by a new measure called the misery index. The easy affluence they had known since childhood was in the process of vanishing. Putnam and Garrett call the period extending from 1960 to 1975 the Long Sixties, and if you ponder the experiences of young people over that 15-year period, you can get a sense of why the idealism they felt at the moment Jack Kennedy summoned them to collective action in 1961 could have dissipated by the mid-1970s, laying the groundwork for the advent of Ronald Reagan in 1981. It was, the philosopher Richard Rorty observed, “as if, sometime around 1980, the children of the people who made it through the Great Depression and into the suburbs had decided to pull up the drawbridge behind them.”

In Walter Lippman’s book Drift and Mastery—published in 1914, the same year Lippman helped launch The New Republic—he described Americans in a state of drift stemming from the enormous changes in their way of life wrought by the Industrial Revolution. Americans were migrating in massive numbers from the small country towns of traditional America to the teeming, impersonal cities of the industrial Midwest and Northeast. There, they found themselves trapped in a system of impersonal wage labor, offering little prospect of eventual escape (long gone was the “Free Labor” system of the Lincoln era, in which young men starting out as apprentices expected one day to run their own show), and also surrounded by a bewildering whirlwind of changing norms and ways of life. They were, to use Lippman’s term, in a state of drift. They felt they had lost control of the direction of history.

Lippman urged America to regain its mastery of history, and he advised that “it has to be done not by some wise and superior being but by the American people themselves. No man, no one group can possibly do it all. It is an immense collaboration.”

The Upswing echoes these sentiments in its own call for a new Progressive movement. Its authors want today’s younger generations to understand that America hasn’t always been as unequal and divided as it is now, that their grandparents and great-grandparents lived in a very different nation, with radically different values: of economic equality, political comity, social solidarity, and a balance of individualism and community, fought for in the social wreckage of the Industrial Revolution. What’s more, before the Industrial Revolution, America wasn’t as it is today either: The country was characterized by a similar blend of individualism and communalism at its founding and in its early decades, when Tocqueville in the 1830s credited the blending of the two with America’s success in creating the world’s first mass democracy.

If the United States is to see the rise of renewed Progressivism, Putnam and Garrett advise, Americans will need “to eschew the corrosive, cynical slide toward ‘I’ and rediscover the latent power and promise of ‘we.’” The Progressive movement was, above all else, a phenomenon of moral awakening, and this awakening occurred at the individual as well as the mass level. “A soul-searching effort on the part of these reformers,” the authors write, “revealed to them their own de-structive individualism, and their own complicity in the creation of exploitative systems—and this realization fueled their passionate efforts to right society’s wrongs.”

Putnam and Garrett see signs of a new awakening in the #MeToo movement; in the March for Our Lives activism spearheaded by the student survivors of the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Florida; in the Families Belonging Together initiative opposing the Trump administration’s inhumane treatment of immigrants at the Mexican border; and in the Reverend William J. Barber II’s “national call for moral revival” with the Poor People’s Campaign. Yet they skirt a crucial issue: As Francis Fukuyama makes clear in his discussion of the twentieth-century Progressive movement in his book Political Order and Political Decay, its moral inspiration was very much rooted in the egalitarian Protestantism dominant in the Northeast and Midwest at the time. It was the Social Gospel campaign of Protestant ministers that countered the ideology of Social Darwinism, and its perverse claim that the theory of evolution justified the inequities of the Gilded Age. With an American left as disconnected from religion as the one we see today, where will the moral fervor for a new movement come from exactly? A single charismatic preacher operating out of North Carolina will hardly suffice.

A moral reawakening, assuming it can be achieved, must then be translated into effective citizen activism. The citizen organizers of the Progressive years took an innovative and open-ended approach to addressing the problems they confronted, with no prior assumptions about how to go about solving them, Putnam and Garrett explain. “No hard-and-fast rule can be laid down,” instructed Theodore Roosevelt in 1901, “as to the way such work must be done.” In the same vein, Putnam and Garrett write that “Progressivism didn’t privilege one type of reform over another, but was instead a holistic reorganizing of society that began at the bottom and was based on a reinvigoration of shared values.” They contrast this political modality with that of socialism, with its rigid, prefabricated solutions designed to be imposed from above, whether democratically or not.

The creative citizen activism that the authors advocate must then burgeon into a “groundswell of agitation,” they stipulate. Today’s nascent movement of citizen resistance is led, they insist, “not by far-left political operatives, as many have supposed, but by everyday people working on problems central to their own lives,” who, they note, just as in the Progressive era, are primarily middle-aged, middle-class, college-educated women. Ultimately, though, this agitation, no matter how spirited and well-intentioned, will come to naught if it does not result in the legislative enactment of concrete and effective policies and programs. And the youthful would-be organizers of a new Progressive movement need to bear that uppermost in mind.

The political anthropologist David Graeber has postulated that imagination—the ability to envision a better future for society, as a guide to action—is the foremost intellectual talent of the left, and he has expressed exasperation that there is so little imaginative thinking on the American left today. The Upswing serves as a call to the generations who have succeeded the baby-boomers to imagine a better future for the American project, and to pursue it. Rather than focusing on the tension between generations—the “OK Boomer” divide—the authors encourage young people to look for an earlier precedent for themselves. They remind us that the problems of today with which the new generations must grapple—the skyrocketing costs of health care, the weakness of environmental regulations, the power of corporate monopolies, and the urgent need for campaign finance reform—are almost exactly the same as those that confronted the original Progressives in their day, even if the solutions to these problems must be new and different ones. The faculty of imagination must be commandeered to create a new civic community for America.

Putnam and Garrett end the book on two notes of caution. First, they warn against the danger of what they call overcorrection. The original Progressives were so successful, they say, because, in contrast to the socialists and Populists with whom they competed, they found ways to put individualistic values—such as private property, personal liberty, and economic growth—on the same level as communitarian ones. The big communitarian overreach of the Progressive era—which helped bring it to an end—was the attempt with Prohibition laws to interfere with what a majority of Americans considered an individual right to consume alcohol as they wished. The Tocquevillian aspiration for a balance between the individual and the community must always be upheld, they insist.

Second, they emphasize once more the crucial importance of building an inclusionary “We” society and reiterate their judgment that the failure last time around to fully incorporate African Americans, other minority groups, and women into the American community played a major role in slowing, and even reversing, the great Progressive upswing of the last century.

In Making Democracy Work, Putnam discovered that the cities of northern Italy where democracy was flourishing best were the very same ones that had been self-governing communal republics in the late Middle Ages. These entities emerged from amalgamations of voluntary associations of residents who had banded together for self-protection and mutual assistance; in other words, they were created from the ground up, just as new civic communities in America would need to be. Machiavelli used the communal republics as models for the civic republicanism (or communitarianism) that he espoused, and he formulated what Putnam called “the iron law of civic community”: “That it is very easy to manage Things in a State in which the Masses are not Corrupt; and that, where Equality exists, it is impossible to set up a Principality, and, where it does not exist, impossible to set up a Republic.”

Progressive President Teddy Roosevelt expressed his vision of the American civic community in words that Putnam and Garrett offer as the final gift of this magnificent and visionary book: “The fundamental rule of our national life, the rule which underlies all others,” Roosevelt told the American people, “is that, on the whole and in the long run, we shall rise or fall together.”