There is, among the works of Philip Roth, a book his friends urged him not to publish. The document, titled “Notes for My Biographer,” is a 295-page rebuttal of his ex-wife Claire Bloom’s 1996 memoir, Leaving a Doll’s House. Bloom had described the pain of his sudden withdrawal from their marriage and cruel and erratic behavior, including his outlandish threat to fine her $62 billion during their divorce. As publicity built around her book, Roth found himself “swamped with anger,” flailing to respond. Another writer his age might not care, he acknowledged, but he did. “I can no longer allow her falsifications to impinge on my personal and professional reputation,” he finally wrote. He combed through the memoir, countering it point by point. By the time his friends intervened, he had accepted an advance and paid a law firm $85,000 to vet the manuscript for publication. “You’re gonna look like a bully,” one warned him. “Don’t do it.”

Roth dropped the project, but it spurred him on with a different quest. He wanted to find a suitable biographer, someone who could refute Bloom for him. At various points he had tried to enlist Judith Thurman and Hermione Lee, both close friends and accomplished biographers. He also approached his friend Ross Miller, an English professor at the University of Connecticut, who had not written a biography before. Roth thought his writing “no jeweled and nuanced thing,” but the prose mattered less to him than a sympathetic portrayal. Roth had cautioned Miller that he did not want this book to become “The Story of My Penis”; it needed to focus on the novels, not sex and gossip. In 2004, with Roth’s somewhat prickly blessing, Miller signed a contract for a “full scale biography.”

But before long Roth cast Miller as another antagonist. He didn’t like the way Miller was conducting interviews, and found his interpretations intrusive. By fax, Roth declared himself “too fucking angry” to talk to his biographer, and came to decry his “mean, insatiably vilifying spirit.” The problem, Miller noted, was that Roth was “surrounded by sycophants.” Meanwhile he joked to a mutual friend that Roth was “writing shit now,” prose that “just lies there like lox.” The two men parted ways, and Roth wrote another rebuttal, also unpublished, titled “Notes on a Slander Monger.”

Enter Blake Bailey, who started work on Philip Roth: The Biography in 2012, after being interviewed for the job by Roth. The author of substantial biographies of Richard Yates and John Cheever, Bailey is much happier than his predecessor—at one point, he reports his delight at overhearing the “muffled streams” of “our greatest living novelist” peeing—and, at over 900 pages, his book sets about addressing a laundry list of Roth’s gripes. Sick of charges of “Jewish self-hatred, misogyny, and general unseriousness,” this Roth has been perpetually misunderstood. People see him as an autobiographical writer, but he’s not! And he’s definitely not the “Philip Roth” of Bloom’s memoir. He claims to regret publishing Portnoy’s Complaint, and he doesn’t know why the Nobel Prize in literature eludes him. In Bailey’s opening vignette, Roth is attending the installation of a commemorative plaque at his childhood home in New Jersey, only a few days after the most recent snub from Sweden. “Today,” he muses, “Newark is my Stockholm.”

It is a carefully constructed scene. We later learn that Roth wrote the plaque himself, in one of several attempts to control his legacy down to the very last word. In his interviews with Bailey, he assiduously makes the case for himself as a man many times wronged, who just wants to set the record straight. Is this biography as revenge? It may be the longed-for rebuttal. But it may also be a cautionary tale in getting the vindication you wish for, even—especially—when the biographer is sympathetic.

In Bailey’s telling, Roth’s life is a story of a great talent, threatened by other people’s desires and demands. Born in Newark in 1933, Roth was “the privileged, the pampered” second son in a lower-middle-class Jewish family. His father, Herman, was an insurance broker; his mother, Bess, an exacting homemaker. It was not a literary household. Herman, like Brenda Patimkin’s father in Goodbye, Columbus, struggled with the conventions of written English; he had an eighth-grade education. Roth remembered only a handful of books in the house growing up. He wrote his first short story under the name Eric Duncan, unsure that someone with a name like his could be a writer.

The boredom and righteousness of the Jewish community in New Jersey was up to this point his main dissatisfaction. After one year at Rutgers, he struck out for Bucknell University and then graduate school in Chicago, where he studied and taught English. The draft interrupted his smooth path through the academy. In 1955, he enlisted. He hated military service and boasted to a friend that he was finding ways to get “out of every indecent, undignified detail.” But the Army may have made him a writer as much as his years in graduate school. Writing was his escape route: He trained as a typist, and, instead of being deployed to postwar Europe, he got assigned to the Public Information Office at Walter Reed Medical Center, then in Washington, D.C.* By day, he composed press releases, and in the evenings, he went back to his desk and pushed himself to become “a strict schedule abiding writer.”

Roth vowed to himself that when he got out, he would “live right up to the hilt, and make these brief years as extravagant as hell.” He was discovering an element of ecstasy in writing. He “paced, bitched, wrote heatedly.” By 1956, he was back at the University of Chicago, discharged from military service early because of back pain. He was writing “a thousand perfect words a day” and completed his novella Goodbye, Columbus in a month. He started selling his stories and writing for little magazines. The New Republic gave him a weekly film column. “I thought, Boy, I’m in it,” he marveled, after visiting the offices of Commentary. He was finding out what kind of writer he could be. He submitted a “satire of ornithologists” to Esquire, which the editor told him was terrible; he had tried and failed to write “a powerful moral document” about an American Jew who travels to Germany to kill a Nazi in revenge. He soon realized that his ambitions were misplaced; that he was best at depicting the idiosyncrasies of the striving, semi-assimilated Jewish community he grew up in.

These were the stories that would break through at the then-newish Paris Review. Rose Styron pulled “The Conversion of the Jews” out of the slush pile and got it published. The editors soon asked him to submit for their short story award, the Aga Khan Prize. Roth sent in “Epstein,” about the midlife infidelity of the upstanding owner of the Epstein Paper Bag Company and the venereal sores that betray him to his wife. The story won—though Roth still had a lot to learn. “It is the first time I have written a story with sex scenes, and it was a delight,” he wrote to friends, “but I don’t know if it is a success.” Drawn to the seedier mechanics of the plot, he was many decades away from the technically extravagant sexual maximalism of Sabbath’s Theater. In a touching scene, the Paris Review’s editor George Plimpton has to correct the young, innocent Roth’s description of Epstein’s sores: “It was clear Philip didn’t know the first thing about what syphilis looked like.”

Roth was feted at the prize-giving in Paris. Soon, The New Yorker took his story “The Defender of the Faith,” about the wheedling Army conscript Grossbart, who shamelessly leverages every aspect of his Jewish identity to guilt his Jewish sergeant, Nathan Marx, into letting him out of duties. Not long afterward, Roth sold his first book, Goodbye, Columbus—which contained the titular novella and five short stories—after a small bidding war. What more success could a young writer hope for? “I shall be twenty-five next week and stouter,” he wrote to his future publisher, “and feel a tiny knife in my side as I race to be a boy wonder.”

Yet all of this talent and promise, Bailey suggests, was about to be jeopardized by the appearance of a uniquely destructive woman.

Roth met Margaret Martinson at the sandwich bar in Chicago where she was a waitress, and for reasons that Bailey never wholly makes clear (“Roth was simply determined to pick up a pretty shiksa”), they started seeing each other. She too had attended the University of Chicago and was an aspiring writer, but got pregnant and had to leave without a degree. A few years older than Roth, she was now divorced, had lost custody of her two children, and was supporting herself. Roth and Martinson seem to have bonded over a sense of sexual adventure—early on, Martinson orchestrated a threesome with Roth and a graduate assistant for the Committee on Social Thought (“Let’s fuck Diane”)—but soon they were fighting and breaking up, and getting back together and fighting more.

A major point in the case against Martinson is that the “deepening turbulence” of their relationship, her “years of constant nagging and irritation,” made it difficult for Roth to write. The account of their relationship reads like a litany of small and not so small acts of career sabotage. When Roth wins the National Book Award for Goodbye, Columbus, she asks him not to fly to the ceremony in New York without her, worried that he will sleep with other women there. She is frequently suspicious of infidelity and doesn’t trust him around her young daughter. She pawns his typewriter and lies about it. She fakes a positive pregnancy test result by buying a stranger’s urine and then tells Roth she will only have an abortion on the condition that they marry immediately after. If Roth experiences the marriage as a protracted nightmare, he experiences divorce proceedings as full-blown persecution. He describes alimony payments as “court-ordered robbery,” and as his success grows, he realizes with terror that he may have to yield the financial rewards to his “worst enemy.”

Of all these incidents, it was the faked pregnancy that had the longest and most destabilizing effect on Roth’s writing. He did, of course, find ways to write about Martinson, the model for Martha Reganhart in Letting Go and Lucy Nelson in When She Was Good; Bailey even credits Martinson with introducing “the sprightly young author … to the darkness of an adult life gone irrevocably awry.” But Roth’s obsession with what he and Bailey refer to as “the urine fraud” kept finding its way into drafts and capsizing them. He tried twice to write a play about the episode. Both attempts fell flat. He wrote about these failures in a discarded draft for a novel. The protagonist reflects that his script was “an indictment and a cry for help”; he had wanted to expose this “crime to the world, which would then issue its verdict: Boy Innocent, Bitch Guilty.” Eventually Roth would have Maureen Tarnopol in My Life as a Man carry out the same deception that Margaret Martinson had in real life, but his desire for a resounding guilty verdict didn’t fade.

Bailey seems determined to deliver that verdict for him. Much that Bailey writes about Martinson is difficult to stomach: One of the first things he tells us about this woman is that her vagina was “withered and discolored” from childbearing, and that Roth was “frightened” to go down on her. Like an adoring wingman who thinks his friend can do better, Bailey expresses his concern that “an unemployed, thirty-year-old … former secretary and waitress” was “an unlikely consort for such a handsome, promising young man,” and notes the abundance of “gorgeous young women” whom Roth “longed to flirt with, if not for Maggie’s hawkish eye.”

Martinson cannot express affection without being accused of trying to tie her man down. When she buys Roth a kitten and reflects that he would make a good father, Bailey sees “the walls closing in.” He cannot narrate the couple’s wedding day without noting in the same breath that the Spode china they received as a gift “ended up in Maggie’s possession” and that she was “eager to get her hands on” some “rainy day AT&T stock,” too. These complaints are puzzling. How does Bailey think divorce settlements work? Was Martinson supposed to leave the marriage with nothing? Bailey writes of her life with little awareness of the difficulties of survival as a single mother in the 1950s. When Martinson pawned Roth’s typewriter, she was out of work and homeless.

As for Martinson’s major deception—the fake abortion—Bailey never connects this incident with similar incidents earlier in the relationship. Roth claimed (and Bailey reiterates) that Martinson’s pregnancy morally compelled him to marry her: “I had married her because I believed I had seriously wounded her in a horrible abortion.” Yet she had already had an actual abortion during her relationship with Roth; he had shown up at the hospital with champagne and flowers, but he hadn’t married her then. In fact, she would get pregnant a second time once they were married, and then, Bailey pronounces, Roth “brooked no discussion.” She was instructed to get another abortion.

Does any of this make a difference? Or is her trickery the worst part of it? One of Roth’s plans to escape was to trick Martinson into moving to New York. He told her he planned to move there, when he would in fact be heading to Palo Alto, California, for a fellowship at Stanford. She would be stranded in a new city alone. He hoped she would be enticed to stay there, away from him, if he could get the magazine editors Bob Silvers and Rust Hills to give her work. These arrangements fell through when he didn’t get the fellowship.

The biography’s animosity toward Martinson is something more than a matter of taking sides in a bitter divorce. There is throughout the book a bizarre aversion to the idea of men running errands: Women who ask their partners to lift so much as a finger to help them are trouble. Susan Glassman, who briefly dated Roth before marrying Saul Bellow, is “a pain in the ass,” who “was forever expecting him to drop everything and take her to the hairdresser or some such.” I blinked when I read this. Later Bailey writes that Martinson “couldn’t resist” interrupting her husband’s work “on the thinnest of pretexts (‘Could you go out and get half a pound of Parmesan cheese?’)” If this request brings on writer’s block, there is a bigger problem than grocery shopping. Women in this book are forever screeching, berating, flying into a rage, and storming off, as if their emotions exist solely for the purpose of sapping a man’s creative energies.

If you believe women tend to act this way, you may conclude that Roth was tormented by monsters. No doubt this was why he reacted with relief when Martinson was killed in a car accident in 1968—or as he stylishly rendered it in The Facts: A Novelist’s Autobiography: “[Y]ou’re dead and I didn’t have to do it.” Yet there is more to any ordeal than what one person felt. Even Roth’s autobiography, which ends with a 35-page response from the fictional character Nathan Zuckerman, doesn’t insist on being the straightforward truth. Bailey could have uncovered the messier reality of all this and shown how Roth selected from it his preferred “facts,” but he doesn’t go to the trouble of finding out what any of the women experienced. They remain caricatures.

Roth’s sigh of relief would not last long. He had drawn criticism from the Jewish community for “Defender of the Faith”; his own mother had asked him if he was an antisemite. If the New Yorker story perpetuated stereotypes, Portnoy’s Complaint did not exactly show American Jews in a favorable light, either. Alexander Portnoy pursues gentile women out of spite (“I don’t seem to stick my dick up these girls, as much as I stick it up their backgrounds”) and deems the burdens of Jewish history irrelevant to him (“stick your suffering heritage up your suffering ass”). Gershom Scholem wrote that this was “the book for which all anti-Semites have been praying.” Alfred Kazin found the book disappointing less for its provocations than for the smallness of its concerns: Whereas Bellow’s Moses Herzog “lived in history; Portnoy lives only through his mother.” But that may have been the point: At his worst, Roth seems to demote the suffering of a whole people in order to make room for his own sense of being picked on.

The novels that followed were never received warmly enough for his liking. From book to book, Bailey expresses Roth’s disappointment at uncomprehending reviewers and prize juries—where’s that National Book Award? And how about that Pulitzer? In his personal life, which Bailey documents fling by fling, Roth now often turns to sensible, accommodating women. In the middle of a break-up, the heiress Ann Mudge says wistfully, “You’re never coming back lamb chop.” Many of his often-overlapping girlfriends hover around college age (“I was forty and she was nineteen. Perfect. As God meant it to be”). His analyst observes that “a mature woman wouldn’t take your shit,” but Roth’s notion of himself as the innocent boy solidifies. In a draft of his 1974 novel My Life as a Man, his protagonist considers that maybe the reason he married a Martinson-like woman was that he was such a good guy: “I married her to be heroic … in politics it was the age of Adlai Stevenson, in literature, the age of Henry James.” His 1983 novel The Anatomy Lesson is a fantasy of male vulnerability, as Nathan Zuckerman’s incapacitating back pain brings him four girlfriends, a “consortium of mistresses” who each serve charmingly as “secretary-confidante-cook-housekeeper-companion.”

Amid all the dating in the biography, Roth the novelist gets lost. His most inventive, formally experimental novels, The Counterlife and Operation Shylock, do not really fit into the sweep of the narrative, not least because the best writing in them has nothing to do with sex. (In fact, the sexy cancer nurse, Jinx Possesski, in Shylock is one of Roth’s flattest female characters, though she has a thankfully small role.) These are some of Roth’s least resentful books; instead of turning inward to relitigate a grudge, they lead outward to a world of intrigue. While The Counterlife starts with an unfaithful husband obsessing over his potency in a New Jersey dentist’s office, it moves to the West Bank, where Zuckerman’s brother Henry has become a settler, and onto a hijacked El Al flight, where Zuckerman is arrested. Operation Shylock takes Roth’s paranoid tendencies and transforms them in a political thriller, where the protagonist “Philip Roth” must track down an impostor who is spreading anti-Zionist propaganda in his name.

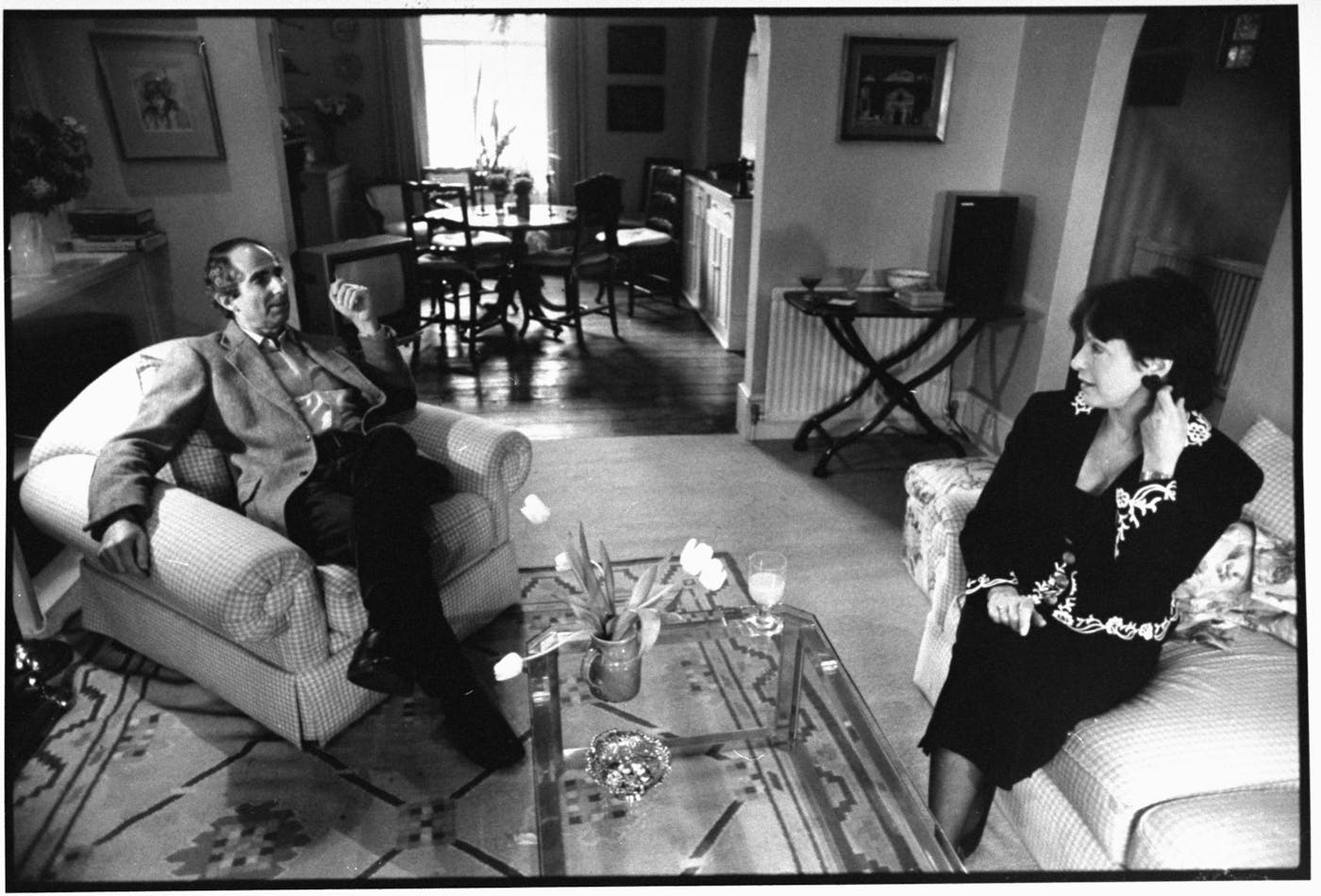

By the time these novels appeared, Roth had become the “schedule-abiding” writer he’d set out to be. Throughout his life he had a habit of urging himself to achieve greatness. “DO NOT JUDGE IT. DO NOT TRY TO UNDERSTAND IT. DO NOT CENSOR IT,” he advised himself in an all-caps memo. His desk later bore notes to self that read “Stay Put” and “No optional striving.” During his 17-year-long relationship with the actress Claire Bloom, he was particular about his writing routine. When they lived together in London, he would start the day with a three-mile walk to work through Hyde Park, work at his studio till 1.30 p.m., stop for lunch at a French restaurant, and then work until six or seven o’clock at night, and walk home.

Roth’s feeling that this routine was under threat, and that he was once again being drawn away from his work—flashbacks to Maggie—is the overarching drama of the second part of the biography. Even though his output remained fairly steady, he laid the blame for this feeling at the feet of Claire Bloom, his partner from 1976 to 1993. Bloom told her side of the story in Leaving a Doll’s House, and Bailey’s chapters (“Entering a Doll’s House”) present the same events but incorporating Roth’s commentary.

A bone of contention in the couple’s marriage from early on was Roth’s animus toward Bloom’s teenage daughter Anna. After witnessing an explosive mother-daughter fight, he took against the child. He came to see home life as “family hell” and vowed that he would not be “defeated by this kid.” He fixated, for some reason, on her weight, writing to friends that she is “fatter than ever” and on a separate occasion complaining that she rejects “the idea of a diet.” He ultimately informed Bloom—in writing—that either Anna had to leave or he would. “Anna was asked to move out,” Bloom wrote ruefully in her memoir. “She was eighteen.”

The opportunity to argue back against Bloom’s book was Roth’s major inducement to go ahead with an authorized biography. But his responses here make him sound even worse. He mocks her reaction to losing Anna: “So somber, so tragic, so tellingly concise,” he tells Bailey, “as if she were writing, ‘Anna was asked to move out. She was two.’” Anna moved back in after a time, and unable to see her as a child, Roth seems to have cast her as a sexual rival. He reports being enraged when Bloom would come to bed “still warm from snuggling Anna’s body.” He recalls being exasperated by her endless chats with Anna about her life and her career. In a particularly egregious act, which he does not deny, he made aggressive sexual advances on a friend of Anna’s. After she rejected him, he made a point of insulting her whenever they interacted. “What’s the point of having a pretty girl in the house if you don’t fuck her,” he says in his defense. Bailey ascribes this to Roth’s “impulse to mock a certain kind of bourgeois piety.” What?

As for Bloom, her original sin was asking Roth to marry her. After a brief period of calm immediately after the wedding, the wheels quickly came off. In one of Roth’s most thinly veiled novels, Deception, he portrayed Bloom as a boring, whining middle-aged wife, while documenting a series of lurid conversations with an eloquent young mistress. When Bloom read the manuscript, she was distraught. In the series of meltdowns that followed, Roth repeatedly recruited surrogates to handle his most delicate affairs. Seeking to appease Bloom, he met up with Judith Thurman, who took him to Bulgari; there they picked out an extravagant ring, for Roth to give Bloom as a peace offering.

Later, when Roth was trying to extricate himself and get Bloom out of their apartment in New York, an impressive cast of luminaries lined up behind him. The writer Francine du Plessix Gray phoned Bloom to tell her that their neighbor Maletta/Inga (Bloom and Bailey use different pseudonyms for this person, who had an 18-year affair with Roth—it’s complicated!) and Thurman “have been to see her and pleaded with her to use her influence to secure Philip the apartment.” The next week, Janet Malcolm also called “on Philip’s behalf.” Although Bloom worried that she would forfeit any right to the home in the divorce, she moved out.

A criticism that long rankled for Roth was Morris Dickstein’s observation that he couldn’t imagine women with complexity. His female characters were either “bitchy castrating women” or “doting sexual slaves.” Hermione Lee later identified four categories: “overprotective mothers,” “monstrously unmanning wives,” “consoling, tender, sensible girlfriends,” and “recklessly libidinous sexual objects.” Roth once defended himself against charges of misogyny by protesting that actually many of his most important professional relationships were with women: his lawyer, some editors, his first agent Candida Donadio, and his favorite teacher at Bucknell. To this group one might add ex-girlfriend Julia Golier, who is now co-executor of Roth’s estate, and Lisa Halliday, who dated Roth when she was in her twenties and he was in his sixties, and later wrote a flattering fictionalized account of a similar relationship in her novel Asymmetry.

Needless to say, a man can like and respect some women, while demonizing and vilifying others. In life, as in his fiction, Roth seems to have sorted women into distinct groups: those who could help him and work things out for him—the facilitators and curators of Rothworld—and those who dared ask something from him (“half a pound of Parmesan cheese”). The second group does not fare well.

Then again, Roth does not come out of this biography looking so great, either, despite getting the chance to tell his side of the story. His final years see a sad procession of young girlfriends floating in and out of his life, as he tries to convert some of them into long-term carers. Falling out of step with his times, he fumes that if you sleep with your students nowadays, “you go to feminist prison.” His notes while writing The Human Stain would not be out of place on an incel message board: “Very upset and can’t understand it.… Hysterical fear of the dick.… The Great Purity Binge.” When the novel is adapted for a film starring Nicole Kidman, he shows up at her hotel in a limo and tries to take her on a date.

Possibly the worst thing you could do for Roth’s reputation would be to defend him on his own terms. His emphasis on settling scores with ex-wives and lovers draws attention to his signal failures of imagination—his lack of interest in the inner lives of women, his limited ability to reconcile his own experiences of pain with the co-existence of others’ suffering. The most successful attempts to soften Roth’s image have tended to portray him as a harmless old man: the elderly man of letters watching Sharknado with Mia Farrow; the bumbling author of a New Yorker blog post about the inaccuracy of his own Wikipedia entry; or his mostly sweet fictional counterpart Ezra Blazer, who buys his girlfriend blackout cookies and pays off her student loans in Asymmetry.

Roth, however, seems to have gone out of his way to prevent a gentler story from being told. The parts of Bailey’s book that trace the unraveling of Ross Miller’s Roth biography are among its most revealing. Not long after signing the book deal, Miller came to suspect Roth of interference: Roth was actively involved in setting up interviews with friends, family, and collaborators, and was even drafting the questions that Miller was to ask them. In one case, he was directing Miller to ask a dying friend to yield up old gossip. Miller was also editing the Library of America edition of Roth’s works, and Roth had inserted himself there, too. As the editor, Miller was meant to provide a 10,000-word chronology of Roth’s life, but Roth wrote it himself and signed Miller’s name to it; he also wrote all the jacket copy himself, claiming he could do a better job.

And Miller was not the only would-be chronicler who got on Roth’s bad side. In 2011, Roth took exception to an essay by Ira Nadel in The Critical Companion to Philip Roth that drew on Claire Bloom’s book. He spent over $60,000 in legal fees to get the offending passage changed. When Roth found out that the same writer was contracted to write a biography of him with Oxford University Press, he had his agent tell Nadel that he would not have permission to quote from his works in the book.

In Bailey, Roth found a biographer who is exceptionally attuned to his grievances and rarely challenges his moral accounting. Yet the result is not a final winning of the argument, as Roth might have hoped. Just as his unpublished rebuttal to Claire Bloom made him sound like a bully, this sympathetic biography makes him a spiteful obsessive. The absence of ironies here, the raw insistence on truth over untruth, are distinctly un-Rothian. They strain oddly against Roth’s own experiments with persona—the play of author and alter ego, of life and counterlife, in endless permutations of self-exploration. If he thought self-justification would be simpler, he should have known better.

*This article has been updated for accuracy.