One evening in January 2015, a mental health counselor named Foad Afshar met with a twelve-year-old boy inside his office in Concord, New Hampshire. Afshar was 55, a gregarious man with eyeglasses, thinning hair, and plans to retire that spring. As a teenager in 1977 he had emigrated alone from Tehran to Massachusetts, fleeing religious persecution. (His family was Baha’i, a non-Muslim religious sect.) “I had $500 and 50 words of English,” he said. He studied psychology and in 1984 moved to New Hampshire. Since then, he had worked at drug treatment centers and psychiatric hospitals, as a school guidance counselor, a special education and ESL director, and in 2005 he opened a private practice, working mostly with children. In 2010, he was elected president of the New Hampshire Psychological Association. When the family of the twelve-year-old first approached him, in November, Afshar had demurred; he had a full caseload and retirement on the horizon. He shared a list of colleagues he recommended. Weeks later, the family called again. The holidays were nearing, and they couldn’t find anyone else. Afshar agreed to provide “a short-term intervention” until the new year, when the family could try again.

The boy, identified in court documents as E.R., was in seventh grade. He played an instrument and club sports and liked to snowboard. In summers he liked to visit a family friend’s lake house on Winnipesaukee. Since his parents’ divorce, when he was five, E.R. had lived primarily with his father and older sister, and recently his father’s girlfriend, with whom the children had a difficult relationship. The girlfriend “yelled” and was “mean,” E.R. said. He began spending more time at his mother’s house, just a seven-minute walk. Because his mother worked overnight as a nurse, and slept during the day, E.R. passed most of his hours there alone—and, soon, getting into trouble. He shoplifted condoms and was caught smoking marijuana on campus before school. He and a friend stole lighter fluid. With a Zippo lighter and a can of Axe body spray, he made a small blowtorch. Knives were discovered in his pillowcase. His father worried he was becoming “a little bit lost.”

Over two months that winter, E.R. and Afshar met five times, on weekday evenings. “He seemed wicked nice,” E.R. said. He liked that Afshar could talk about sports, and that his office had games: a basketball net, a shelf of toys. E.R.’s father, retreating to a waiting room down a short hallway, noticed his son emerging from appointments seeming “relaxed,” and his mother told a pediatrician that E.R. was making “great strides.” In their fifth session, on January 6, 2015, according to E.R. and to a Merrimack County jury, Afshar slipped his hand beneath E.R.’s shirt and rubbed his fingernails across the boy’s chest and back. Then he reached down E.R.’s pants and rubbed his penis.

Because of Afshar’s stature in the community of mental health providers, and because of the shock of the allegation, coverage of his trial flooded local news outlets. There were front-page headlines, opinion columns, and radio reports. In the 17 months between arrest and trial, no other victims came forward. Police searched Afshar’s office, computer, and clinical files, and found no evidence of wrongdoing. “You don’t need it, if you believe [E.R.],” assistant County Attorney Kristin Vartanian argued to jurors. “You do not need any additional evidence to convict the defendant. You don’t need fingerprints or DNA, you don’t need an eyewitness to the crime.”

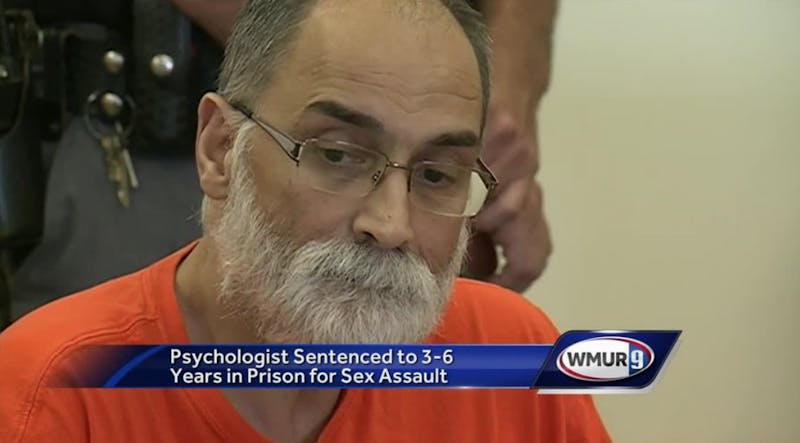

In June 2016, jurors found Afshar guilty of aggravated felonious sexual assault, simple assault, and two counts of unlawful mental health practice. He was sentenced to three to six years in prison, forbidden from unsupervised contact with children outside his family, and ordered to register as a sex offender.

That might have been the entire story—had the verdict proved any more than an unfortunate milestone in the case, had it not sent forth ripples of controversy and condemnation, had the episode not revealed the limits of a criminal justice system, had a culture in reflection not faced obvious challenge—if the outcome provided anyone with any closure at all.

On a chilly, overcast afternoon in March, I met Kristin Vartanian. In person, she is friendly and disarming, with a habit of calling minors “kiddos,” even in discussion of criminal cases. She had just come from three days of professional training in sexual assault cases, especially against kiddos, and she told me sadly that the images she’d seen, of crime scenes, would stay with her. Since her prosecution of Afshar nearly two years earlier, a contentious law had been proposed in her state: House Bill 106, requiring corroborating evidence, beyond an allegation, in cases of sexual assault where the defendant has no prior conviction for the crime.

The reaction was national. Reason magazine called it “ridiculous” and “nonsense.” The Daily Beast ran a headline: “Lawmaker to Rape Victims: ‘Prove It.’” A police sergeant in Concord, where Afshar was tried, condemned the bill as “nothing short of a Pedophile Protection Act,” a phrase that was picked up by the Associated Press. The bill was also troublingly vague, Vartanian, who now works as a prosecutor in Rockingham County, told me. Even she and her colleagues could not reliably predict the effect of the law if it passed. “It depends on the definition of corroborating evidence. If you don’t define that, we’re really getting murky.”

A line I’d heard before traveling to New Hampshire was that the state requires no corroborating evidence to convict a person of sexual assault. This is true but misleading. Actually, in most states, no corroborating evidence is required for any conviction at all. Criminal laws do not stipulate evidentiary minimums. In the wake of an allegation, police investigate; based on that investigation, a prosecutor chooses whether or not to press charges; based on those charges, a jury chooses whether or not to convict. This sequence applies whether a thousand pieces of evidence emerge or none of them do. What New Hampshire was trying with HB 106 was not to eliminate an exception, but to create one.

It is not the first state to do so. Until the last half-century, states commonly required corroboration. “The law is well established,” read a 1904 court ruling in Georgia, “that a man shall not be convicted of rape on the testimony of the woman alone, unless there are some concurrent circumstances which tend to corroborate her evidence.” A 1959 law in New York, in the words of one historian, required corroboration of “each material element of the offense—force, penetration, and identity of the accused.” These and other statutes grew from a concern that jurors could be moved to sympathy by any description of so heinous an offense, no matter how specious—and from misogyny, rather explicitly. “Women often falsely accuse men of sexual attacks to extort money, to force marriage, to satisfy a childish desire for notoriety, or to attain personal revenge,” read a 1970 argument in the University of Pennsylvania Law Review. Two years later, in The Yale Law Journal, a contributor remarked, “It is generally believed that false accusations of sex crimes in general, and rape in particular, are much more common than untrue charges of other crimes,” adding later, that “the dangers of unfounded rape charges are particularly common and dangerous when made by children.”

By the 1980s, owing mainly to the women’s rights movement and to a dawning awareness of the realities of sexual assault, a majority of such laws were repealed. Stephen Schulhofer, an expert in criminal justice at NYU Law School who specializes in sexual assault, told me, “Victims can make false accusations of theft, robbery, fraud. The mere possibility of a false accusation doesn’t generate these kinds of requirements anywhere else.” Arbitrarily steepening the barriers to some criminal verdicts but not others can make legitimate convictions impossible, he said. “We have this philosophy that it’s better for nine guilty people to go free than for one innocent person to be convicted. This is more like letting 999 guilty people go free.”

Today, 36 states and the federal government do not require corroborating evidence for a conviction of sexual assault. Neither does the Military Code of Justice or Guam or Puerto Rico. The remaining states do so only in limited circumstances. Massachusetts requires corroboration if an alleged victim’s testimony is “discredited or contradicted by other credible evidence.” Missouri requires it if testimony is “in conflict with physical facts, surrounding circumstances, and common experience.” Arizona requires it if “the story is physically impossible or so incredible that no reasonable person could believe it.” No state has a corroborative policy specific to children.

Nonetheless, the actual practice of criminal justice means that many victims of sexual assault do require evidence for their claims to be received seriously, since, well before persuading a jury, he or she must persuade officers and then a prosecutor. Joe Cherniske, who co-led the prosecution of Foad Afshar with Vartanian, told me that most cases brought forward by his office do include corroborating evidence, regardless of statutory requirements. The Gundersen National Child Protection Training Center, perhaps the foremost organization in America for investigating crimes against children, recommends the collection of such evidence, as studies show it increases the odds an allegation will result in formal charges and confessions. According to the National Sexual Violence Resource Center, corroboration is helpful to “avoid the normalization of victim blaming” and for pursuit of sexual assault cases as more than “he said, she said.”

A wrinkle is that corroborating evidence is often unavailable. Or, rather, it depends on how one defines the term. A majority of sexual assaults are committed outside the view of potential witnesses. “And a lot of these cases aren’t reported right away,” Cherniske said. “They don’t get reported within that day or that week or that month. By the time we bring them into the hospital, there’s not necessarily going to be physical evidence of trauma.” Circumstances are especially difficult when the victim is a child. Because young victims are most often violated by adults they know and trust, even timely examinations seldom reveal signs of physical resistance, like torn clothing or bruises. An assault that does not include penetration—only groping or fondling—rarely leaves visible marks. According to the Department of Justice, as many as 40 percent of youth victims of sexual assault show no symptoms, and many do not report at all, frightened of retaliation from the abuser or from their parents.

However, a wider array of evidence might be understood as corroborating, even psychological symptoms such as nightmares. “Those who say there’s no corroborating evidence are thinking very narrowly,” Victor Vieth, the founder of the Gundersen center, told me. “They’re thinking of hair, DNA, the things you see on television dramas. I’ve never worked on a case of child abuse where, if you look hard enough, you won’t find corroborating evidence.” Vieth invited me to imagine a child who describes that his or her assault occurred in a room painted blue. Police should obtain a warrant and visit the room. Were its walls blue? If so, that was corroborating evidence.

No text of HB 106 clarified the term, and this was what Vartanian meant by murky. How were authorities to interpret corroboration? It would be difficult to overstate the magnitude of the decision. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that approximately one in six boys, and one in four girls, are sexually abused before they turn 18. In many states, laws governing the investigation, prosecution, or sentencing of child abuse are named for the children whom adult authorities failed. Brooke’s Law, in Vermont. Megan’s Law, in New Jersey. The Jessica Lunsford Act, in Florida. The Jacob Wetterling Crimes Against Children Act. The Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act.

I wondered whether, in Vartanian’s view, the Afshar case included any corroborating evidence. “Absolutely.” E.R. was able to describe the interior of Afshar’s office, including what furniture he sat on. “All that was corroborated and found during a search warrant. Dr. Afshar admitted that he used methods that our victim talked about.”

Neither of those was in dispute, I pointed out. Everyone, including Afshar, agreed the child and therapist had met for five appointments, four of them before the day in question. It stood to reason that E.R was able to describe the interior of the room. Everyone also agreed on what treatment methods the therapist was using, and that no credible application of them included any contact with genitals. I confessed it was difficult for me to see how either fact clarified the truth of what happened—what, in a meaningful sense, they were corroborating.

That was a question for jurors to decide, Vartanian answered. And jurors had decided.

In late 2014, E.R. was nearing the end of his first semester of seventh grade, and his home life, he would later testify, “was a cesspool.” He signed up for a program at the Boys & Girls Club. Enrollment required that he pass a physical, including, he believed, a genital exam. The prospect made him uneasy. “I don’t like when they put their hand down your pants or anything like that.” He mentioned the physical to Afshar, who decided that, alongside E.R.’s more abstract complaints—turmoil at home, misbehavior at school—this seemed like a specific, tangible treatment goal. Together they set about trying to address it.

First Afshar suggested that E.R. ask his physician to examine him “above the clothes.” This succeeded: According to the pediatrician’s clinical notes, and to E.R’s mother, who was present for the appointment, the pediatrician agreed his discomfort was typical for a boy E.R.’s age, and the genital exam could be deferred until he was older. Next Afshar led E.R. through relaxation, visualization, and breathing exercises, and a technique called systematic desensitization. Gradually, Afshar would expose E.R. to triggers of his anxiety, to alleviate the stress they provoked. For a phobia of bees, a counselor might expose a patient to a buzzing sound, without any sting—in this way, an anxiety could slowly be mollified.

E.R. had named a phobia of genital exams. At their fifth appointment, after asking his permission, Afshar touched the boy’s forearm. Then, according to Afshar, he instructed E.R. to touch his own belly, and to imagine that Afshar’s hand was doing the touching. This was the nearest Afshar could get to the trigger of E.R.’s anxiety, he later explained, without crossing an obvious boundary. According to E.R., something very different happened. Afshar reached beneath the boy’s pants and underwear. “I didn’t know what to do,” E.R. later testified. “I was in shock, so I just let it happen.”

A week passed uneventfully. Ten minutes before their next scheduled meeting, however, the boy told his sister what happened. Together the siblings told their father, who canceled the appointment. The following day, after a discussion between his parents, E.R.’s mother phoned a guidance counselor at the middle school, who phoned the Department of Children, Youth, and Families, which contacted police.

The next afternoon, a pair of detectives knocked on the door of Afshar’s office in Concord, interrupting a session with a patient. He asked if they could return later. (Afshar, who maintains his innocence, later said he assumed that someone in his family had died, and the detectives had come to notify him.) Over his shoulder, detectives noticed his patient was a child, and they pressed to speak immediately.

When they asked if any patient had recently terminated counseling, Afshar said one had and, realizing they must mean E.R., said he thought he knew where a misunderstanding might have arisen. He explained the upcoming genital exam, the tangible goal, and the therapeutic techniques he’d used. He demonstrated on one of the detectives. The detectives asked to see Afshar’s clinical notes, but Afshar didn’t have any: After intake and orientation, when Afshar filled out six pages of assessment forms and a mental status exam, he hadn’t taken any further clinical notes in five weeks. Detectives left empty- handed. A day later, Afshar reconstructed his clinical notes on E.R. from memory. Four days after that, on January 20, detectives returned to his office with a search warrant. (A further complication existed, besides Afshar’s note-taking habits. Due to what he attributed to disorganization on his part, in December 2014, his license lapsed with the New Hampshire Board of Mental Health Practice. He quickly realized the error and filed for renewal, but in the interim he continued his appointments. Two of his meetings with E.R., including the one in question, occurred while Afshar was practicing without a license.)

Though detectives searched Afshar’s office and computer, neither turned up anything incriminating or suspicious. Because eight days elapsed between the incident and its reporting to police, and because its description included no fluid or penetration, detectives decided it was unlikely that E.R.’s pants or underwear would offer any evidence. They never collected or examined them for DNA or skin cells. At trial, an expert for the state confirmed that systematic desensitization was a “generally accepted treatment method,” especially for phobias, and was often paired with relaxation and breathing techniques, precisely as Afshar described. But it was also vital to take clinical notes, and to obtain informed consent from a parent, neither of which Afshar had done. A result was confusion. Although it turned out no genital exam was required after all, understandably E.R. did not know this in advance and, since he was the one communicating with his therapist, Afshar didn’t know it, either. Meanwhile, E.R.’s father knew of the upcoming exam, and mentioned it to Afshar, but offhandedly; he was only making conversation. He regarded the exam as separate from his son’s behavioral issues. Sitting in the nearby waiting room, E.R.’s father didn’t know touch therapy was occurring at all.

It didn’t help that both police and prosecutors seemed unfamiliar with psychotherapy. At their initial interview inside his office, Afshar had told detectives he understood E.R. was in a bit of a “time crunch” to deal with his phobia, because the genital exam was required to enroll at the Boys & Girls Club. Detectives mistook this as a therapeutic technique—“time crunching,” like visualization or hypnosis. The phrase made its way into their official report, and prosecutors raised it at trial. What was this time crunching? “There is no such thing as ‘time crunching,’” Afshar testified. “That’s the stupidest thing I ever read in that police report.”

“I assume that you feel betrayed by [E.R.]?” Cherniske asked.

“Not at all.”

“According to you, he made all this up?”

“I don’t know what happened,” Afshar said. “I don’t know if he made it up, I don’t know if other people made it up. I have no idea. I know the allegations are false. Totally, completely.”

E.R. was 14 by now. Like many 14-year-olds, he could be endearing: On the stand, when he told Vartanian he no longer hung around with the classmate with whom he was caught smoking, and she asked why, E.R. replied that he found the boy “annoying.” What made him say that? “He doesn’t care what happens. Like, he doesn’t respect anything.”

He could also be funny. What was his sister like? Vartanian wondered. “Grumpy.” Was she ever not grumpy? “A rare chance.”

At times he could be conspicuously deflecting, as though he were coached. Was he aware that shoplifting was wrong? “Yeah.” What had made him do it, then? “Peer pressure, and I didn’t want to not fit in. I felt nervous, like that if I didn’t fit in, they would make fun of me and judge me.” Had he wanted to do those things that got him into trouble? “No.”

At times he could be achingly sympathetic, even as the reason aroused curiosity. Within days of his mother’s testimony that her ex-husband’s new girlfriend, whom E.R. disliked, made E.R. feel he was losing his father’s attention, E.R. agreed on the stand that since reporting the assault everyone had been “comforting” and “sympathetic” toward him, and he had gotten a lot of “positive attention.”

“And your mom and dad have been united in supporting you, like you had never seen them united before?” Afshar’s attorney asked.

“Right.”

“That’s a good thing, isn’t it, for mom and dad to get along?”

“Yep.”

“In fact, they get along better now than they have ever since they got divorced, right?”

“Uh-huh,” E.R. said. “This is definitely the best in a long time.”

Also like many 14-year-olds, E.R. was not always perfectly honest. “He lies a lot,” his sister had told detectives, though she insisted he wasn’t lying about this. At their last appointment, in fact, Afshar had confronted E.R. about two apparent lies. E.R. had told the counselor he was Facebook friends with someone who Afshar happened to know had no Facebook account. He also told the counselor he’d never had a girlfriend. Then E.R.’s father mentioned his son having recently broken up with one. In their session on January 6, 2015, Afshar asked E.R. about these inconsistencies. A week later, E.R. told his father he was groped.

Vartanian and Cherniske each told me, separately, that prosecutors routinely know more than circumstances permit them to introduce at trial, though both declined to say if this were true of the Afshar case specifically. In a file at the Merrimack County courthouse, I discovered a portion of what they might have been hinting at. Some of Afshar’s supporters were publicizing that he had passed a pair of lie detector tests a court ruled inadmissible at trial. This was not entirely the truth. Actually it was detectives who invited Afshar to take a polygraph, during their visit to his office, and Afshar declined, saying—according to detectives’ notes—that such exams were “unreliable,” and he felt “too anxious” for an accurate result. Eight days later, Afshar did take a polygraph, administered by a private provider, not police. He passed. His attorney showed the results to police, who concluded that the questions in the exam were too vague. So Afshar returned to the private provider, who rephrased his questions. Again Afshar passed; again the results were shared with police. This time, among several problems with the test, a departmental expert concluded that Afshar “appeared to be using counter measures.” Eventually both sides agreed to withhold any mention of polygraphs from trial. Afshar’s two passing grades later became public knowledge. No other facts from the episode did.

In the same file, I found a document that was never introduced in any motion or hearing. It was a letter of support from a patient who’d met Afshar on and off for a decade, beginning when he was twelve, the same age as E.R. After reading it, detectives phoned him to follow up. “He said Dr. Afshar would massage his muscles all over his body, to include his back, shoulders, arms, and abdomen,” detectives wrote in their notes. The patient, now a young man, suffered from irritable bowel syndrome, and he told them Afshar seemed “knowledgeable.” The counselor would “massage and push on his abdomen in order to increase circulation to his intestines to help his IBS.” Sometimes this happened above the young man’s clothes; sometimes it happened beneath them. “[He] said Dr. Afshar sometimes pressed on his abdomen over his clothes below his ‘belt line’ but he denied that Dr. Afshar ever touched his genitals.”

The courthouse file included the letter. “Never have i felt uncomfortable by his touch in anyway nor do i believe it was in anyway meant to be sexual,” the young man wrote. “One reason I have seen him for counseling is for my troubled ability to trust people and yet i still trust him completely. I hate to see how much good he does to selflessly help people being thrown away by these trying circumstances.”

The list of organizations that opposed HB 106 included some unusual allies: the County Attorneys Association and the Department of Safety, but also the state chapter of the ACLU. A House committee determined the bill would leave the state “with the weakest sexual assault statute in the nation.” A press release by the New Hampshire Coalition Against Domestic and Sexual Violence decried the proposal as “a blueprint for how to get away with sexual assault,” and announced it “would require either DNA evidence or an eyewitness,” a claim that, while untrue, reflected the widespread confusion about what corroborating meant. A public hearing in February 2017 stretched nearly four hours when 120 people showed up. Reporters for New Hampshire Public Radio described attendees wearing stickers that read, I believe victims. Others wore different stickers: Justice for Foad. The bill proved so controversial that one of its co-sponsors later declined to discuss it with me at all; another withdrew her support and voted against it. “It was a major mistake,” she told me. “I really thought I was doing an OK thing. That bill was the hardest lesson I ever learned.” At the end of 2017, the proposal was tabled indefinitely.

Still, the original controversy persisted. If HB 106 was no answer, then what was? If certain ills plague any law that requires corroboration, others plague any case that proceeds without it. A case like this presents obstacles for everyone. For victims, it means no proof of their experience, and therefore their trauma is too often dismissed. For the accused, it means the absence of such proof does not reliably exculpate them. A defense attorney is tasked with countering what evidence prosecutors introduce. If this evidence consists solely of the word of the victim, then that is what he counters. An attorney for a client like Foad Afshar has little choice but to accuse an alleged victim like E.R., however politely, of lying. Wasn’t this precisely the treatment victims were asking to avoid, especially in the present moment? An adult with a conscience need pay only the barest attention to current events to recognize how often our culture has dismissed or belittled the victims of sexual assault, how seldom we have heard them. Wasn’t it vital to treat victims more decently, and didn’t that mean believing them? But how far was it right to extend that principle—and given the presumption of innocence, weren’t our laws designed not to? Without evidence, what is the alternative?

When I mentioned these concerns to Jennifer Long, the CEO of AEquitas, a national resource for prosecutors of gender-based violence, she agreed the quandary I was noticing shaped many cases that lacked corroborating evidence. But it was also the underlying dynamic of any case of sexual assault, she said. “All you’re doing is playing into what people believe already, to blame the victim. Challenging the veracity comes along with the court process.” Or, as Joe Cherniske told me, “The premise of the prosecution of these cases, where there’s no one else present for the crime, is that the victim has to be telling the truth. And the premise of the defense is that the victim is either confused, mistaken, or lying. I don’t know how else they could go at it.”

An additional frustration is that, with so many facts undisputed, each side is simply left to argue, in testimony and character witnesses, how best to interpret them. A trial with no evidence, or at least no conclusive evidence, yields no discoveries. Only inferences. Most of those who believed Afshar guilty assumed that more victims existed, though with none coming forward, and also statistics about underreporting, this was impossible to prove or disprove. The appearance of no other victims showed either that Afshar was a successful criminal or that he was an innocent man. For much of his career, Afshar treated the neediest of children, including those with disabilities or from broken homes. This showed that he was either predatory or altruistic. To clients and their parents, Afshar often gave his personal email address and cell phone number. This showed that he was either grooming or generous. Upon hearing the accusation against him, Afshar urged detectives to consider his reputation—“that he had been in business for about 30 years, that nothing like this had ever come up before,” one officer recalled. This showed that he was either credible or manipulative. E.R. had a recent history of misbehavior and dishonesty. This showed the boy was unreliable. Or else it revealed why Afshar had targeted him.

Before shuttering his practice, Afshar maintained a professional web site, and when detectives visited it, they noticed it “goes to great lengths to sell his qualifications and services to help children.” This made sense for a therapist who worked primarily with the young. But another interpretation existed. The web site “by itself does not imply pedophilic or criminal tendencies on his part,” read a detective’s supporting affidavit for a search warrant. “But it cannot be ignored that sexual predators that target children frequently choose careers which provide them with unsupervised access to children.” The affidavit continued, “His self-described ‘passion’ for children’s well-being, his obvious admiration of their world-view, and his hope that he does not lose his ‘sense of childhood’ all take on a sinister tone in this light. Although Dr. Afshar communicates noble intentions for his patients, it is noteworthy that the web site and its language are also consistent with a sexual predator attempting to lure additional child targets.”

In her closing argument, Vartanian looked similarly to Afshar’s credentials. “He expects you to believe him. It’s clear that he’s accustomed to that, people taking him at his word.” When I spoke to her, she mentioned Jerry Sandusky and Larry Nassar, two convicted serial sexual assaulters, both of whom are in prison. How did those abusers continue for so long? “People have a hard time with anyone who’s in a position of authority, and had success, and has the respect of their community, believing that they could harm a child,” she said. No parent wants to face the possibility of his or her own child in danger, so they simply refuse to believe it is possible. Vartanian, and several others I spoke with, are parents; they can understand this impulse, even sympathize with it. But they believe it is a form of denial. “We’re all opposed to child abuse in the abstract,” Victor Vieth told me. “We’re seldom opposed to it when we see it up close and personal. And the reason for that is that it’s someone we know.”

After Afshar was convicted, a web site was set up, justiceforfoad.com, for people to contribute to his legal fund. (In all, more than $50,000 has been raised.) A newsletter sends updates on his case to subscribers. “It would not be unfair to compare these dynamics to those of the Salem witch trials,” one read. Another included a letter from Afshar, from inside prison. “I can’t tell one day from another, and live in a space the size of a car parking space with no direct natural light and lots of noise—just loud, incomprehensible, often violent, crude conversations intertwined with the clanging of heavy metal doors…. I cope one hour at a time.” Newspaper photographs during this period, from a mugshot and appearances at appeal hearings, show a paler, gaunter Afshar, in prison garb, with an unkempt beard and eyes downcast. These photographs became their own controversy, a reporter for the local newspaper, the Concord Monitor, told me, when readers began phoning to complain. “They said, ‘You’re making him look like a criminal. He’s not a criminal.’ What we would explain was, he had been convicted of this crime, and we need a photo of him to illustrate our story.”

A therapist often has no secretary or receptionist, no assistant or support staff. How are they to protect themselves, if they are innocent? After Afshar’s sentencing, some mental health care providers in New Hampshire reportedly began to change the way they provided treatment, including video recording sessions, out of fear that an unfounded accusation might destroy their livelihoods. Others have ceased accepting into their treatment any child diagnosed with certain personality disorders, or whose family life seems adversarial, meaning a child whose parents are separated or divorced. In other words, precisely those children who might most need counseling. How many providers have altered their practice in response to Afshar, or whether they tally enough to seriously reduce treatment opportunities for children in the state, is uncertain. The community of therapists, like the community of sexual assault survivors, is not a monolith. Neither are those the only two constituencies with meaningful interests at stake. Nor is New Hampshire the only place. Every other state is in the same position.

The creator of justiceforfoad.com and the newsletter is a psychologist named Mike Kandle, who works from a home office in a hilly, wooded neighborhood in Durham, near the University of New Hampshire. For someone so outspoken about the vulnerability of his profession to unfounded allegations, he seemed to practice in a particularly vulnerable setting, I noticed. He agreed this was true. It was the first home office he’d owned. He gestured toward a wall of large sliding glass doors, which, he maintained, made his office more “transparent.” He said, “I would’ve recognized the client that put Foad in jail as a high-risk client, and I would have declined to take them altogether.”

Early in his career, before moving to Durham, Kandle once worked with a twelve-year-old boy—the same age as E.R., he noted. The boy’s mother could be volatile, and, after one of her tirades at home, the boy confided to Kandle that he sometimes felt angry toward his mother and her treatment of him. At their next session, the woman appeared alone in Kandle’s office. “I’m concerned about what’s happening inside your office with my son,” Kandle still recalled her saying. “For all I know, you could be molesting him.” Her tone and expression left Kandle with little doubt what she meant. “A warning shot over the bow,” he told me.

Kandle long ago stopped seeing children from similar circumstances. When he learned of the allegation against Afshar, he assumed it was “phony,” since Afshar was “well known” and “well admired.” On the New Hampshire Psychological Association listserv he began posting his thoughts on the case. When leadership grew sensitive about this, Kandle invited anyone who was interested to email him for continued updates. The result was Kandle’s ongoing newsletter. “The whole drama created a lot of anxiety and tension and conflict for our profession.”

I asked Kandle if he was troubled at all by what might be cast, generously, as Afshar’s inattention to paperwork: the lapsed license, the absent clinical notes. Those were “irresponsible” and “careless practice,” Kandle said. They were not criminal, however. Or unheard of. Professionals in his field, as in every field, sometimes grow busy and fall behind. Perhaps it warranted a complaint to the licensing board. Whether Afshar had molested a patient was an entirely different question, Kandle said. “Those careless lapses on his part were used to augment the argument, in court, that this is an unethical, unprofessional, rogue, untrustworthy bad actor. It just defies credibility.”

The episode made Kandle sympathetic to HB 106, and initially he submitted a letter in support. “I just could not understand how allegations of this nature could be judged without any evidence whatsoever. Part of me thought it made sense to require some.” Then he read and listened to counterarguments. These, too, he found persuasive. “These things take place in private,” he said sadly. “It’s hard for anyone to know what actually happened.” If that mother, early in his career, had been determined? “My career would probably have been destroyed.” On the other hand, certainly there were abusers out there. “I don’t have any wisdom in terms of how cases like this should be handled,” he said. “That’s beyond me. I see the problems. I see the controversy.”

What is the solution? A small number of models have emerged in recent years as substitutes for the criminal justice system, including civil litigation, mediation, and the restorative justice movement, but those are designed to resolve conflicts, not uncover truths. They are helpful only if a shared understanding exists that an offense occurred. I mentioned to Stephen Schulhofer that a case like Afshar’s appeared to stand at a vexing intersection—a heinous offense, a common lack of evidence. How equipped are the courts to accommodate these variables simultaneously? Schulhofer referred me to the famous line by Winston Churchill—that democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others. “What’s the alternative?” Then he answered his own question. “History gives us some answers. We used to have trial by ordeal, or trial by battle. We used to tie people up and throw them in the water. If they floated, that meant their soul was hollow and they were guilty. If they sank, they were innocent, and they got a Christian burial. There are many alternatives. But you can see right away that they’re even worse.” An impartial jury, a unanimous verdict, a burden of proof beyond a reasonable doubt—these and other protections exist to balance competing priorities humanely. It was no surprise to Schulhofer that some cases laid those priorities bare. “We need to have a system for enforcing the law. At the same time, we don’t want to put people behind bars if there’s a chance they’re innocent. In an organized society, that’s an existential problem.”

In September 2017, after publishing my first book—which told, in part, a story of wrongful conviction—I spoke with New Hampshire Public Radio. The next morning, Foad Afshar emailed me. “It touched my heart that someone would take the time, stay dogged and be dedicated to the welfare of a wrongly convicted man,” it read. “Your work was especially poignant to me because I too was wrongly accused and convicted.” I knew of his case, but only barely; given all the controversy, on the phone I expected to hear desperation, but he sounded calm and reflective. Now I realized how long he’d had, more than a year, to adjust to an abruptly changed life, regardless of its cause. I told him I held no assumption he was innocent. It was important to me that he knew. His reply surprised me. “That’s reasonable,” he said. “I appreciate you telling me.” He recognized he couldn’t expect every stranger to believe him.

I phoned E.R.’s parents, who told me they preferred not to speak with a reporter, though not before his mother asked me if I knew of the web site for Afshar’s supporters. “It’s hard, as a parent, not to look at that,” she said. I’d reached her in a fallow period, when things had quieted for her family between court rulings, but she knew it wouldn’t last. “You feel blindsided sometimes. Things feel settled, and then all of the sudden, boom.”

After the trial verdict, Afshar hired a new defense attorney, Ted Lothstein. Lothstein hired an investigator who found and interviewed the twelve jurors from the trial. Two of the twelve, the investigator discovered, were survivors of sexual assault. Neither had mentioned this fact before trial. They’d been asked at least twice: once on a written questionnaire, again verbally during selection. One juror, a young woman, was assaulted in middle school. She had not disclosed her experience because it was “private.” Another, an older man, was assaulted by his babysitter as a boy. “I don’t see myself as a victim,” he said. “That’s not my lifestyle. Therefore, the answers that I gave were true, to my knowledge.” He’d been elected the jury foreman.

No rule prohibits a juror from serving on a trial for a crime he or she has personally endured. (Amanda Grady Sexton, director of public affairs at the New Hampshire Coalition Against Domestic and Sexual Violence, told me that, if a jury was meant to represent one’s peers, the prevalence of sexual assault was a relevant fact. “If you take away people who have had a sexual assault in their life, you certainly don’t have a jury of your peers. Because your peers have been sexually assaulted.”) A requirement is simply that each juror be “fair and impartial.” In the view of Vartanian and Cherniske, both jurors still were; some vaguely phrased queries had simply confused them. The pair withheld out of misunderstanding, not dishonesty. This carried no suggestion of bias.

Lothstein—and eventually an appellate judge—disagreed. In March 2017, a court vacated Afshar’s convictions and released him from prison. Prosecutors appealed that decision in April; another judge denied them in May. Prosecutors appealed to the New Hampshire Supreme Court in January 2018. In October, the court ruled against them.

Today Afshar is free, but perhaps only temporarily. Merrimack County is entitled to re-prosecute him. Five days after the state Supreme Court upheld the dismissal of Afshar’s verdict, Joe Cherniske announced the state would “not pursue a second trial at this time.” This did not exclude pursuing one in the future. In New Hampshire, the statute of limitations for aggravated felonious sexual assault against a minor expires “within 22 years of the victim’s eighteenth birthday.” The question on which the appeal succeeded was procedural. It does not address the essential matter of what happened. In this permanent uncertainty, a portion of New Hampshire residents believes Afshar guilty. A portion believes him innocent. Any further trial verdict or court ruling is likely to worsen division, not alleviate it. So is any legislative proposal.

Afshar has three children. The two eldest, who are in their mid-twenties, told me that no legal outcome could make them feel vindicated. That was the wrong word. What they hoped to feel, both told me, separately and unaware the other had said it, was relief. The eldest, Lilly, happens to be a survivor of sexual assault. “So many people are,” she said. One of her earliest memories is her father admonishing her for squashing bugs. “He would always tell us, ‘Those bugs have families. They have kids. How would you feel if someone came and crushed you?’ That’s where I learned everything I believe in.” She does not look forward to more court proceedings. “It’s so hard to feel confident and secure after what happened.” This is an easy sentiment to appreciate, and also to imagine extending to others. E.R. has finished middle school and begun high school. In a retrial, he and his family would be forced to choose whether or not to testify again.

I asked Mike Kandle to consider a terrible possibility. What if, tomorrow, another victim came forward, with a story similar to E.R.’s? What would Kandle’s reaction be?

“I’d be shocked,” Kandle said. “I’d be confused. And if it were a credible accusation, from a credible source, I’d find it heartbreaking. I have no interest in protecting sexual abusers. I work with plenty of victims of sexual abuse. I’m keenly aware of the indignities and harms of justice not being served for them. I would never support anybody where there are legitimate accusations, even if I was a friend of theirs.”

“What would there need to be, for it to be a credible claim?”

“That’s a good question,” Kandle said, and he paused to think.