The headquarters of the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God does not resemble your typical megachurch. Its eighteen stories dwarf the big-boxes of the Texas and Missouri exurbs. Behind pillared walls of imported granite and marble, a 10,000-seat sanctuary features neither crosses nor organs, but a menorah motif running from entrance to pulpit. Men in shawls and skullcaps that look a lot like Jewish tallis and yalmukahs conduct ceremonies next to Hebrew-inscribed Tablets of Stone and a gilded Ark of the Covenant. The building is meant to be a supersized reproduction of the biblical Temple of Solomon, but by way of Caesar’s Palace.

This is São Paulo, not Vegas or Jerusalem, and the men onstage are Pentecostal pastors, not rabbis. To be more precise, they are Neo-Pentecostal pastors, practicing a syncretic stew of the prosperity gospel, millenarianism, miracle healing, demon invocation, and exorcism, while boasting a level of Judeophilia weird even by the generous standards of Christian Zionism. Once a spiritual outlier, the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God (UCKG) stands at the forefront of Brazil’s rapid transformation into a Catholic-minority country. Its seven million members constitute Brazil’s second-largest Protestant denomination, after the Assemblies of God coalition.

In the UCKG, the Holy Spirit does more than purge demons. It sets believers up for the acquisition of great wealth. The living proof is 74-year-old Edir Macedo, a former street preacher and lottery worker who over the course of four decades has built the UCKG into a billion-dollar church-media juggernaut. This past autumn, he used the levers of this power to help elect Brazil’s first Evangelical president. With the ascension of the far-right ex-Army captain Jair Bolsonaro, Macedo cemented his status as a pivotal figure in the future of post-Catholic Brazil.

“Nobody can rival the electoral discipline of the Neo-Pentecostals” of the UCKG, says Andrew Chesnut, professor of religious studies at Virginia Commonwealth University and author of two books on Brazil’s religious economy. “Macedo was at the vanguard of popularizing exorcism and prosperity theology. Now, he’s arguably the most important Evangelical figure in Latin America.”

The UCKG is the foundation of a global operation that includes a 49-percent stake in a private Brazilian bank, Banco Renner, and a growing media empire, Rede Record, whose properties include Brazil’s number-two television network. In the run-up to October’s election, Macedo used the latter in a powerful demonstration of how Evangelicals are challenging the institutions of a weakened Catholic establishment, notably Brazil’s dominant media company and TV channel, Globo.

“Macedo’s church-media complex does more than proselytize—it expresses and directs the extraordinary growing power of Evangelicals, and especially Neo-Pentecostalism, which is a clear threat to traditional and popular Catholicism,” says Ana Keila Mosca Pinezi, an anthropologist of religion at Federal Universal of Triangulo Mineiro in the Brazilian state of Minas Gerais. “The Neo-Pentecostal churches, led by Macedo, have become electoral breeding grounds for conservative candidates. Their power has spread from the peripheries to the heart of politics at every level.”

When Macedo completed his $249 million headquarters in 2014, his point of comparison wasn’t John Hagee’s megachurch or Pat Robertson’s TV studio. It was the Christ the Redeemer statue atop Mount Corcovado, overlooking Rio de Janeiro, the symbol of Catholic dominance since 1921. In interviews, Macedo made sure to note that his Solomonic church was nearly twice as tall.

Jair Bolsonaro’s victory on a far-right platform was powered by historic levels of support from Brazil’s Evangelicals, 40 million and counting, three quarters of whom practice one or another strain of Pentecostalism. As a bloc, they voted three-to-one for Bolsonaro, a portent of a historical shift in the politics of the world’s most religious nation. “For the first time, [Evangelical] voters, who are usually divided, opted as a majority for one candidate,” noted the Brazilian daily Extra.

Macedo’s church is not new to politics. It has always backed and opposed candidates and parties, usually by placing them inside narratives about demons and hellfire. The social-democratic Workers’ Party was a tool of Satan, harboring plans to shut down Evangelical churches—until it became the vehicle for the massively popular President Lula da Silva, and political calculus dictated that it wasn’t so evil after all. Lula fell in a corruption scandal in 2010, and after a hesitant interlude backing his hand-picked but unpopular successor Dilma Rousseff, Macedo turned on the Workers’ Party again, this time for Bolsonaro. He did so with a brazen flexing of his media influence. His TV channel, Record TV, and news website, R7, served as reliable sources of friendly coverage for Bolsonaro, constituting an alternative universe from that found in Globo outlets. (Journalists at both later publicly denounced management for pressuring them to slant coverage, with some resigning in protest.)

Record outlets also promoted a rumor, spread widely through WhatsApp, that Workers’ Party candidate Fernando Haddad had developed a “gay kit” to promote homosexuality in schools. On January 8, Macedo’s son-in-law and a leading UCKG bishop, Renato Cardoso, used the Record TV show Intelligence and Faith to denounce the “fake news” attacks of Globo and other broadcasters over the years.

“Macedo uses his cable channel as a kind of Fox News for Bolsonaro and his preferred candidates, providing all positive coverage, all the time,” says Nelson Jobim, a former TV Globo news editor and correspondent for Jornal do Brasil. Jobim notes that Globo has been struggling to keep its audience, and has been forced to moderate its content to appease Evangelical boycotts. Bolsonaro has threatened to cut millions in government ad spending on Globo if it pursues critical coverage, and shift the ad money to Record. “Macedo is building a kind of counter establishment,” he says.

Macedo’s media operation is part of a plan for Brazil that, like his ersatz Solomonic Temple, takes its inspiration from the Torah.

In 2008, Macedo published a book, Plan for Power: God, Christians and Politics, with a heavy focus on Jewish history as a parable for the Evangelicals as God’s Chosen People, a premise that will be familiar to students of the American Evangelical movement. Macedo argues that God has a “dream” to free nations from the godless left and their cultural agenda, just as the Jews were freed and brought to the Promised Land. “God has a great national project developed by Himself and it is our responsibility to put it into practice,” writes Macedo. All that’s required is for Evangelicals to understand their power to implement God’s plan.

The establishment of the State of Israel opened the operational era of God’s plan. Since then, “the sleeping giant” of Evangelical Christianity has awoken, and Brazil is at the heart of the unfolding Biblical drama. “To be an Evangelical in Brazil is like being a foreigner in Egypt at the time of the Pharaohs,” writes Macedo. “Moses’ mission was to liberate the people of Israel, recover their citizenship and guide them to possession of their own kingdom,” he continues. “This book is like the burning bush that revealed God and his great national project to Moses.”

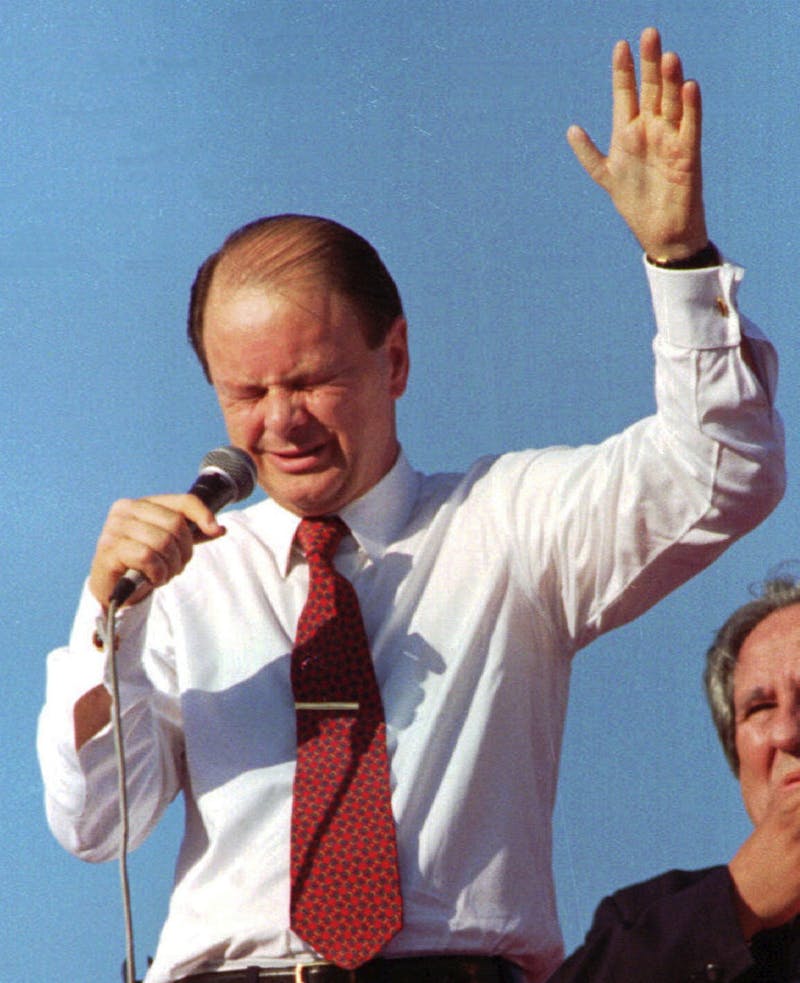

Macedo in action does not possess the power of a Hollywood Moses, or even a cartoon hellfire and snake-handling Pentecostal. He is bald, thin, squinting into the light, a bit shy, with a birth defect resulting in slightly deformed hands. His preaching relies on quantity as much as quality. Hours and hours of it. He talks quietly: “Do you love your wife? Yes or no? Of course you do. Amen.” The sermon drifts, while the congregation nods along. And then you realize that, somehow, he has started talking about the “well-known” danger that Satanists will kidnap your children and sacrifice them. Yes or no? That demons will take you if you don’t pay your tithes. Amen. That he is a poor man and asks only that you give all your money to God. Yes or no? But all in the same soft, reasonable-seeming voice, as if what he is saying is the most obvious thing in the world. If a demon-possessed congregant collapses in front of him, he steps diffidently over him, never missing a beat.

Pentecostalism has always been a religion of the poor, and is especially so in Brazil, where a quarter of the population, 55 million people, live in poverty. The religion arrived in Brazil just a few years after William Joseph Seymour, a one-eyed itinerant preacher from Louisiana, began holding “Baptisms of the Spirit” in the living rooms of Los Angeles’s black working poor. In 1910, two Swedish immigrants to America brought Seymour’s fire to the rubber-boom slums of the Brazilian Amazon. Amid the dense urban squalor of Belem and Manaus, they performed faith healing—cura divina—for indigenous and migrant workers ravaged by the gastrointestinal and infectious diseases rampant in areas without clean water and overrunning with human and animal waste. As the services grew, so did the first Pentecostal churches. They drew so many from the cities’ large leper populations, they were barred from attending.

“Even if the afflicted eventually succumbed to malaria [or] yellow fever … the therapeutic value of prayer, anointment with oil, and laying on of hands proved real,” writes Andrew Chesnut, the Virginia Commonwealth University professor, in his book, Born Again in Brazil: The Pentecostal Boom and the Pathogens of Poverty.

Poverty has provided the impetus and backdrop for Pentecostalism’s rapid 20th-century growth in Brazil and throughout the Latin world. This was especially true during the late 1970s, when Macedo founded his church in a former funeral parlor in Rio. The 1970s was a decade of rising inflation and deepening poverty in Brazil. By 1980, more than a third of rural citizens were undernourished. Pentecostal churches promised health and wealth, in a style that borrowed from, and resonated with, the “demon-filled” religious groups of Afro-Brazilians, in which Edir Macedo dabbled as a teenager.

“Pentecostalism found a fertile terrain for development in Brazil for two main reasons: society’s syncretic and intensely spiritual and mystical cultural-religious basis, and its economic and social inequalities, slums and social exclusion, ripe for a message of material and spiritual salvation,” says Donizete Rodrigues of the University of Beira Interior.

Between 1970 to 2010, the Evangelical (mostly Pentecostal) population grew from five to 22 percent of Brazil’s population. During an early 90s growth spurt, a galaxy of Pentecostal denominations, small and large, were opening new churches at the rate of one per day. The UKCG was in the forefront, with overflowing coffers that funded expansion into Argentina, Chile, Ecuador, and Colombia, and later to Europe, Africa and, with mixed results, the United States.

Ana Keila Mosca Pinezi, the anthropologist at Federal Universal of Triangulo Mineiro, says Pentecostalism feeds into the Brazilian tradition of expecting a messiah figure to rescue the nation, which has origins in myths from the days of Portuguese rule. Lula was the most recent of these figures, and his fall opened a sustained period of scandal and political crisis that allowed Bolsonaro to claim the mantle. The image of the “messiah” was perhaps even stronger during Bolsonaro’s campaign than Lula’s. Having helped destroy the credibility of the opposition, and attained the power to mute and counter criticism from other public figures and institutions, Brazil’s right-wing Pentecostal religious celebrities have emerged as highly influential voices in society.

This influence is built from the money of indigent congregants, who are systematically targeted with warnings about the “godless left.” Macedo’s fortune, possibly the largest of any religious leader in the world, is the fruit of a notoriously aggressive tithing culture. UCKG membership—the majority female, poor, and drawn from the country’s African-descended, Indian, and mestizo communities—are asked to donate a minimum of 10 percent of their income, plus any extra “sacrifices” they can afford. Tithing can take up one-third of every service, and often resembles a shakedown. “They intimidate people who visit the church,” says Nelson Jobim, the journalist. Pastors may use an open Bible as a kind of fetish, entreating the crowd to cover it with cash, checks, watches, and jewelry. In the São Paulo headquarters, a conveyor belt behind the pulpit carries every holy haul directly past the gilded Ark to a safe room offstage. To stoke the spirit of giving, the voice of Satan himself sometimes rumbles out of congregants’ mouths during exorcisms to describe hell in low, guttural dialogue straight out of a grindhouse horror flick.

Macedo’s love of money is no secret. In 2009, Globo aired a video from 1995 showing Macedo laughing like a low-rent mob boss as he divides up the week’s take with his lieutenants. He has been accused multiple times of corruption and links to organized crime. Carlos Magno de Miranda, who ran the church’s Brazilian operation while Macedo established the UCKG’s U.S. operation in the late 1980s (there are tens of thousands of church members in California), has consistently claimed that Macedo did business with the Cali cocaine cartel in Colombia. He asserts that, in December 1989, he and his wife personally helped transport hundreds of thousands of dollars plus a bag of diamonds from Medellin to Brazil by private jet. This money, he alleges, was used to finance the acquisition of Record TV.

Macedo laughed off the charges; the Colombian police took them more seriously. After arresting and extraditing a senior cartel member named Victor Patiño to the U.S. in 2002, they discovered the Colombian representative of Macedo’s church, Maria Hernández Ospina, living in one of his properties. (Brazil’s leading news weekly, Veja, reported in 2009 that the Brazilian Organized Crime Unit had been asked to investigate allegations of UCKG money laundering by the Colombian police, but said they had forwarded the dossier to the U.S. authorities because Macedo held a U.S. passport. No prosecution resulted in either country. When contacted by The New Republic in December of last year, an FBI spokesperson neither confirmed nor denied having a file on Macedo, saying only that the agency is obligated to investigate any credible allegation of a violation of federal law.)

Then there is the case of Grigore Avram Valeriu, a Romanian lawyer who headed the church’s legal department in São Paulo. In 1995, he sued Macedo for the return of a family collection of gold jewelry he donated to the church. Valeriu claims church employees melted down the pieces into ingots and smuggled them out of Brazil to one of Macedo’s homes in the United States—a claim backed up by Miranda. Valeriu has set out detailed allegations in books and articles and on TV.

The church no longer bothers to deny the allegations. And if Macedo and his entourage did once traffic illicit jewels, their days of worrying about airport bag searches are long gone. Since 2006, Macedo has traveled by private jet on a Brazilian diplomatic passport, a privilege previously granted only to senior Catholic clergy.

Having seemingly established de facto legal impunity, Macedo glories in the repetition of old charges and the launching of new press attacks, using them as further proof of Satan’s desperate campaign to defeat him. Despite many attempts at prosecution, he was only jailed once, in 1992, for 11 days. A photo of him sitting in a jail cell holding his Bible is one of his most valuable advertising images. A self-produced 2018 Macedo biopic called Nothing To Lose was the most successful Brazilian film ever, beaten only in absolute ticket sales by The Avengers. The poster is a glamorized version of the jail photo. Left-wing journalists point out that the movie played to empty theaters in which Macedo’s organization bought all the tickets and didn’t even bother to give them away.

The Catholic Church has made adjustments in an

attempt to stop the bleeding of converts to Pentecostalism. The Church’s so-called “charismatic renewal

movement” has borrowed some of the entertainment trappings of Pentecostal

services, with the Canção Nova, or New

Song movement, targeting youth with stadium shows and radio programs. But this

has also moved the Catholic Church in the direction of a fundamentalism and conservative

politics that increasingly plays into the hands of the Evangelicals.

“Pentecostalism has been so successful in Brazil, especially since the 1970s, that in order to compete, both the Catholic Church and other Protestant denominations have had to Pentecostalize, offering spirit-filled worship that is very similar to that found in Pentecostal churches,” says Chesnut. A recent Pew survey found that about half of Brazilian Catholics now identify as charismatics, practicing a Catholicism that can look and sound a lot like Pentecostalism with a Pope.

The Church hierarchy, meanwhile, has taken a more conciliatory approach to its brashest challenger. In the past, Catholic bishops and archbishops denounced Macedo’s operation as criminal and blasphemous, with its blessed envelopes for donations and bottles of magic oil from Israel. But in 2016, the Archbishop of Rio, Cardinal Orani Tempesta, openly supported the successful candidacy of Macedo’s nephew and UCKG bishop, Marcelo Crivella, for mayor of Rio. (When Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu visited a group of Brazilian Evangelicals in Rio last December, it was Crivella who welcomed him and hosted the ceremony.)

Politically, the Bolsonaro government provides a window into what Mauro Lopes, editor of Brazil 247 and a leading liberal journalist, sees as a convergence between right-wing Catholic fundamentalists and the Evangelicals. “The Catholics of the extreme right supported Bolsonaro in the elections and now they are receiving him as one of their own,” he says. “[This alliance] is getting clearer every day.”

This Catholic-Evangelical alliance reflects Bolsonaro’s own identity. Although now officially Born Again, he has not renounced his Catholicism. The make-up of the new government is similarly divided: Bolsonaro’s minister for women, family and human rights is an Evangelical pastor, Damares Alvez; his foreign minister, Ernesto Araujo, is a right-wing Catholic intellectual who quotes Wittgenstein and gives his Biblical quotations in Greek.

Bolsonaro’s “guru” on the moral turpitude of the left, meanwhile, is a Virginia-based philosopher, Olavo de Carvalho, who argues that the left in Brazil is controlled by a corrupt elite that has abandoned its Marxist roots in favor of a “cultural Marxism” that promotes gay marriage and feminism. Carvalho also seems to believe that TV forms the intellectual and emotional lives of Brazilians, claiming that the 30 people at the top of Globo control the entire country.

How this arrangement of forces evolves, at least in the short term, depends on the performance of Bolsonaro’s government on behalf of a newly unified Evangelical vote. A nationwide poll from Datafolha from mid-January shows large majorities, up to 70 percent of respondents, disagree with his actual policies. His promise to provide security was immediately challenged by an armed insurgency from drug gangs across Ceará state, to which his government had no new response. “They will not be able to solve the serious problem of violence,” says Donizete Rodrigues, who studies Brazilian politics at the University of Beira Interior in Lisbon. “Bolsonaro represents the military class, which has already shown itself unable to contain the violence in Rio de Janeiro.”

Corruption scandals, meanwhile, have already begun swirling around Bolsonaro and his family, leading to a sense of business as usual. God seems to have sent some fresh challenges, too: The collapse of the Brumadinho dam in January is an epic catastrophe. The surgery that saved Bolsonaro’s life after he was stabbed during his election campaign—surgery he has described as a “miracle,” and a sign that he was chosen by God—has led to complications that have put him back in hospital.

Macedo, meanwhile, has been quiet since the election. Rodrigues suspects he has more pressing concerns than the vicissitudes of national politics. “My guess is he’s more interested in the development of Brazil CNN, a possible competitor, whose incoming CEO, Douglas Tavolaro, is a former longtime Record executive,” says Rodrigues. Whatever happens with Bolsonaro or the new cable network, Macedo is surely looking ahead. If he understands anything, it is the many forms of power and what they can accomplish, in concert, not over years but decades.