Pork rinds in Tabasco sauce. Cheeseburger pizza. Well-done steak with ketchup.

Cory Booker can’t eat any of these presidential favorites. The U.S. senator from New Jersey, who announced his candidacy for president earlier this month, is a vegan, meaning he doesn’t eat food that’s made of, or from, animals. Meat is off the table, as is anything with milk, cheese, or eggs. So Booker can’t indulge in smoked salt caramels, as Obama did, because they contain milk chocolate. He can’t even eat the jelly beans that Ronald Reagan loved because they’re made with gelatin, which includes animal collagen.

Booker is looking to make history with his 2020 bid. America has never elected a vegetarian president before, much less a vegan. Before Booker, a vegetarian had never even been elected to the Senate before. (He says he switched fully to veganism on Election Day 2014.) There are no self-identified vegans currently in the House of Representatives, and only a handful of vegetarians.

Some might argue that there’s a dearth of plant-eaters in public office because there aren’t that many in the U.S. overall. Around 8 percent of Americans identify as strict vegan or strict vegetarian, a figure that has remained steady for the last two decades. But that’s still about 26 million people who have barely had any representation in Washington. Their numbers are similar to other chronically underrepresented identity groups. LGBTQ Americans make up only 4.5 percent of the population. Black and Hispanic Americans make up about 13 and 18 percent, respectively.

The political and cultural forces that privilege white, straight, Christian men in the halls of power are well known. But why do voters consistently put meat-eaters in the White House? How hard would the meat industry—and meat-lovers—fight to keep that in place? Booker’s candidacy provides a unique opportunity to find out.

The power that meat plays in American politics has never been truly tested before. Ben Carson is a vegetarian, but he never really talked about when he ran for president in 2016. It didn’t shape his political identity.

Booker talks about his diet all the time. When he campaigned for Hillary Clinton in 2016, he joked that he was campaigning as her VP—or “vegan pal.” He posts pictures of vegan food to his Twitter and Instagram feeds. He serves vegan dishes to members of Congress. He talks about the benefits a vegan diet could have for African Americans, who suffer disproportionately from heart disease and high cholesterol. If he won the Democratic nomination, Booker would become the most high-profile plant eater in the country—after Beyoncé, anyway.

The 49-year-old senator makes a moral argument for his veganism. “I began saying I was a vegetarian because, for me, it was the best way to live in accordance to the ideals and values that I have,” Booker, who did not respond to my requests for an interview, told VegNews recently. “You see the planet earth moving towards what is the Standard American Diet. We’ve seen this massive increase in consumption of meat produced by the industrial animal agriculture industry. The tragic reality is this planet simply can’t sustain billions of people consuming industrially produced animal agriculture because of environmental impact.”

Still, Booker has said he doesn’t believe his diet will be a factor in the minds of 2020 voters. “I think people are concerned about what kind of leader I’ll be,” he told The Atlantic’s Julia Ioffe last year. “When I go around New Jersey, nobody’s asking me about my personal life.”

Lawrence Rosenthal, who heads up the Berkeley Center for Right-Wing Studies, disagrees. “The likelihood is good the [Republicans] will go after Booker for this,” he said in an email. There is “considerable precedent,” he argued, for Republicans using personal behavior such as diet to portray Democrats as elitist and out of touch. A 2004 attack ad against Howard Dean, for example, portrayed him as “latte-drinking” and “sushi-eating.” The idea, Rosenthal said, was to “play into the ‘us versus them’ sentiment (largely resentment) that is the prime motivator of populist politics—the ‘real Americans’ versus the (in this case cultural) ‘elites.’”

Obama experienced something similar during his first presidential run, in a pseudo-scandal known as “Arugula-gate.” At an Iowa farm in 2007, Obama railed against the high price of produce in America. “Anybody gone into Whole Foods lately and see what they charge for arugula?” he said. “I mean, they’re charging a lot of money for this stuff.” This was used by the right as evidence that Obama had “simply worn silk stockings and rode in limos far too long.”

Presidential candidates from both parties often use food as a way to relate to voters on the campaign trail. But what constitutes relatable food is almost always unhealthy and animal-based. At the Iowa State Fair, presidential candidates seek photo ops with a 600-pound cow carved out of butter, fried candy bars on sticks, and hot beef sundaes. By campaigning as a vegan, Booker “risks coming across as removed from the hoi polloi,” Michael Dorf, an animal rights law professor at Cornell, wrote last year. “He cannot show his love for all things Americana by eating a stick of deep fried butter at the Iowa State Fair.”

It’s also possible that, in an era where “Soy Boy” has become a popular alt-right insult, Booker’s conservative opponents will use his veganism to belittle him. “The idea that soy is a phytoestrogen, and thus men who consume it are less masculine than meat-eaters, is often expressed by people on the far right,” said George Hawley, an assistant political science professor at the University of Alabama. Hawley doesn’t believe the far-right will be as active in the 2020 election cycle, but mainstream Republicans still use food to attack liberals. Ahead of last year’s midterm elections, Senator Ted Cruz attacked his opponent, Beto O’Rourke, by claiming he “wants Texas to become like California, right down to the tofu.”

But one should not expect to find disdain for Booker’s veganism exclusively on the right. Americans from all political leanings tend to find vegans, well, annoying. Meat-eaters often feel that vegans are morally judging them, or even trying to impose their diets on everyone else. Booker’s opponents, especially those who disagree with his environmental positions, may appeal to those sentiments for campaign ads.

Pundits have already shown it’s done. In a 2015 op-ed in The New York Post, Eliyahu Federman accused Booker of “animal-rights extremism” for co-sponsoring a bill limiting antibiotics in livestock, supporting New Jersey legislation to ban gestation crates for pigs, and pushing for a no-kill animal shelter in Newark. In a then-recent interview, he wrote, “Booker talked as if it’s all personal, explaining how ‘being vegan for me is a cleaner way of not participating in practices that don’t align with my values.’ Problem is, he plainly wants to impose those values on the rest of us.”

Such attacks seem all but inevitable as the presidential campaign season accelerates. But that doesn’t mean they’ll work. Strict vegetarians and vegans may not be growing as an interest group, but Americans are warming to the idea that they should be eating more plants—not just for the environment, but their own health. People who identify as “flexitarians”—eating mostly plant-based, but cheating a little—now make up about a third of the population, and 52 percent of people report trying to incorporate more plant-based meals in their diet.

The meat and dairy industries haven’t taken this cultural shift lightly. As the popularity of plant-based products grows, the dairy industry is lobbying Congress and the FDA to demand that soy and almond milk producers stop using the word “milk” on their labels, and the beef industry wants to make sure plant-based burgers can’t use the word “meat.” The beef industry also spent millions making sure the Department of Agriculture didn’t listen to scientists, health and climate advocates who said nutritional guidelines should be changed to recommend Americans eat less meat.

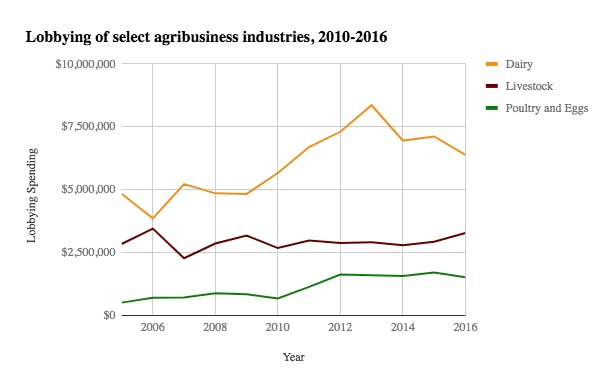

The meat industry has considerable political muscle to flex. It contributes about $894 billion in total to the U.S. economy, according to the North American Meat Institute. “That size translates into political influence,” The Atlantic reported in 2015. “In 2014, the industry spent approximately $10.8 million in contributions to political campaigns, and an estimated $6.9 million directly on lobbying the federal government.” An OpenSecrets analysis of agribusiness lobbying shows that the meat and dairy industries’ political spending spikes as demand for those products fall. How will they respond when a vegan starts making waves on the campaign trail?

Even the Iowa State Fair now has vegan options. “Cory Booker can come to my stand,” said Connie Boesen, a Des Moines City Council member who’s been running her Applishus stand for 34 years. She sells multiple things on a stick: peanut butter and jelly, fruit, and even salad (essentially a skewer of cubed peppers, mushroom, carrots, cucumbers and lettuce). If Booker doesn’t want to partake in the usual candidate photo-op of flipping a pork chop, Boesen said, “I’ll invite him to come slice an apple.”