One morning in May, on the fifth floor of an office building in the St. George neighborhood of Staten Island, New York, five mothers and seven small children sat in a circle, singing a song to the tune of “Frère Jacques.” One by one, in Spanish and English, they made their way around the room, repeating each phrase sung by a gregarious developmental pediatrician: “Where is mom? There she is. How are you today, friend? Play with us.”

The room was sunny, with views of New York Harbor and the soaring spans of the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge. The walls were painted a reassuring pastel yellow, and it was decorated with plush, child-size armchairs and padded floor mats. Behind a toddler-scaled wooden table, baskets woven from rainbow-dyed yarn overflowed with soft toys. Once they finished singing, the children were let loose to explore, alongside their mothers and several clinicians, who sat on the floor beside them, speaking little but encouraging everyone to play.

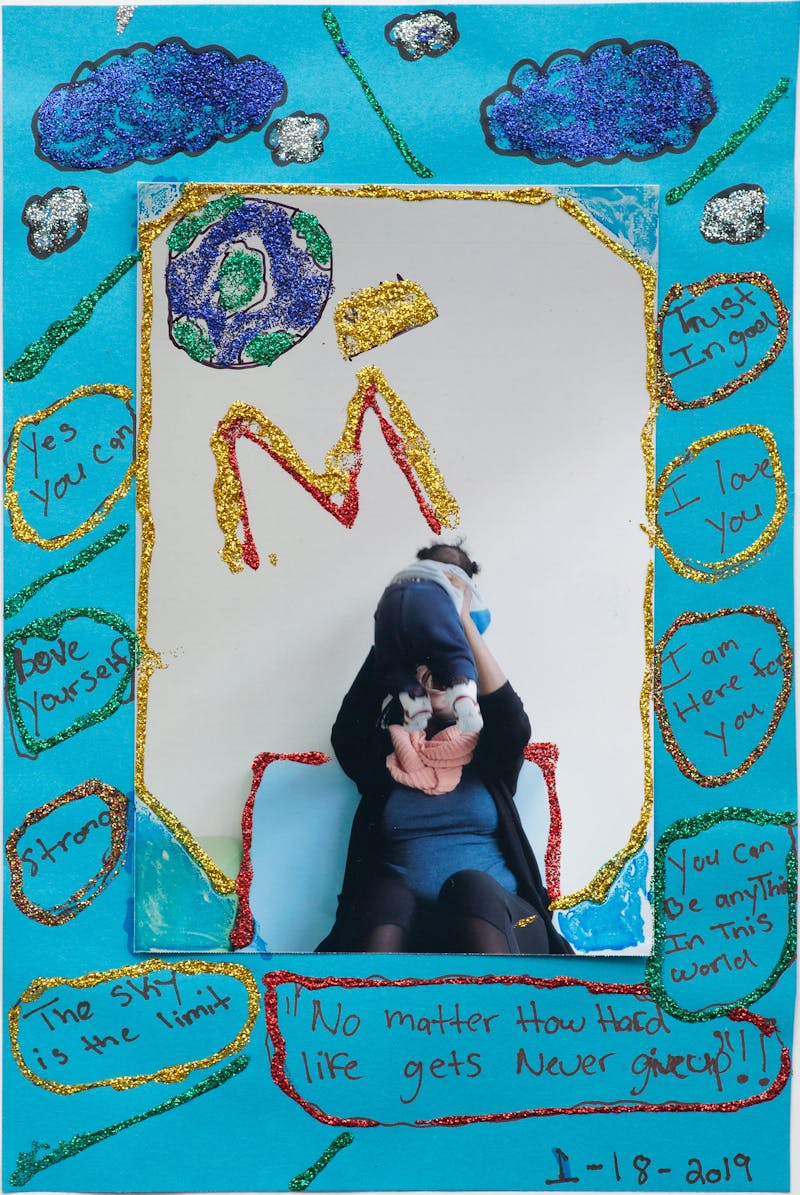

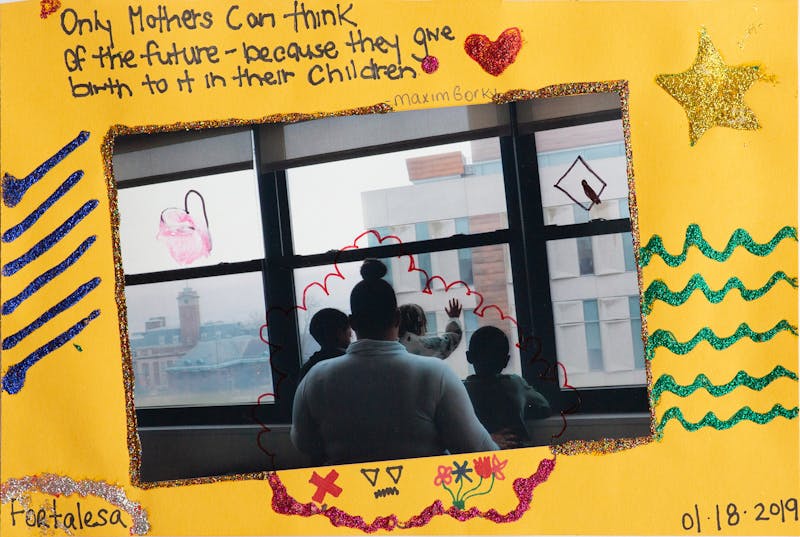

After an hour, the mothers left the children and went next door, to a room with adult-size chairs, for an hour of grown-up talk with Dr. Anne Murphy, a psychologist and founder of the Group Attachment Based Intervention (GABI) program. Three days a week, families with children up to three years old come to GABI centers in St. George and six other New York City neighborhoods for two-hour drop-in sessions, during which parents—low-income, often socially isolated parents—can meet in a welcoming, nonjudgmental environment.

The GABI centers are designed to be high-end experiences, with inviting rooms, upscale furniture, and the sort of “Mommy and Me” vibe you might find in the more affluent parts of Brooklyn or Manhattan. Staff members put together videos documenting the progress the children make, note how the mothers take their coffee, and even on occasion call them in the evenings to check in, if they know they’ve had a stressful day. They are the sort of places you’d want to bring your kid, if you had the money to spend.

The mothers in Staten Island were largely not at the GABI center out of choice, but because they had to be; most, if not all, had open prevention cases with the Administration for Children’s Services (ACS), New York City’s child welfare agency.

Murphy founded the first GABI center at the Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx in 2010. In 2017, ACS partnered with her to expand the program and open centers in every borough, in areas with frequent reports of child abuse or neglect—terms that can encompass a wide range of circumstances, from bruising and other visible signs of mistreatment to things like frequent absence from school, excessive fatigue or hunger, or simply walking home alone. Many calls to the city’s child abuse hotline come from teachers and hospital staff, who are required by law to report signs of abuse or neglect. In Staten Island, most of the reports come from St. George and neighboring Stapleton.

The goal of the GABI program is to provide support to parents and keep problems from escalating to the point where children need to be removed from their homes and placed in foster care. It is guided by the fact that, while serious child abuse does occur, it’s rare, and many issues that fall under the broad umbrella of “neglect”—which alone accounts for 73 percent of all allegations of child maltreatment made to ACS—are simply the everyday struggles of low-income families. In New York, the ten neighborhoods with the highest number of ACS cases, mostly in the Bronx, also represent the lowest incomes, highest unemployment, and greatest income-to-rent disparities in the city. Eight of those neighborhoods are the top places from which families enter homeless shelters. They’re also neighborhoods inhabited predominantly by people of color. “It’s not neglect,” said Jeanette Vega, the training director at Rise, a New York nonprofit that advocates for parents with open ACS cases. “We’re poor—this is poverty.”

This recognition that poor parents need help, not suspicion and condemnation, represents a substantial departure from the understanding many families have of ACS. All too often, family defense advocates say, ACS caseworkers visit families in the middle of the night—a tactic that is supposed to be reserved for emergencies in which children are in imminent danger—demanding that parents wake their children so they can inspect their bodies for bruises, interview them alone, check their bedrooms, and take stock of the food in the kitchen cupboards. Preventive services like parenting classes or counseling sessions for mental health, substance abuse, or domestic violence—technically voluntary, but refused at parents’ risk—are often preventive in name only and do little to address at-risk families’ greatest needs, only increasing the burdens on parents who are already stretched thin, making it more likely that they will be forced to relinquish their children to foster care. “With some cases, I almost struggle to use the word ‘services,’ because I think most families wouldn’t describe them as services,” said Chris Gottlieb, the co-director of the Family Defense Clinic at the New York University School of Law. “People call me all the time, saying, ‘I reached out to ACS for help, and it destroyed my family.’”

At the GABI center in St. George, one woman with a quiet voice and long, dark hair described her terror when ACS banged on her door in the middle of the night, demanding to speak to her children. “I was so scared,” she said. “I thought they were going to take my kids.” Another mother nodded her agreement. “They want to put you in that state of fear,” she said. A third spoke of how she’d been taken from her own mother at age eleven, separated from her younger brother, and shuffled through nine foster and group homes, some of which were abusive. She emerged traumatized and struggled to rekindle her relationships with her siblings. And now, as a parent, she said ACS continued to hound her, showing up at her door or at her daughters’ school in response to what she said were false reports of domestic violence, waiting for her to slip up. “For people like me, who’ve been in the system,” she said, “ACS is a place I hate.”

The women viewed the GABI program differently, however. At the center in St. George, they felt respected, even loved. “You’re thinking of ACS,” said one mother, “but then you think, ‘No, I’m going to the GABI program. It’s completely different.’” The GABI initiative, along with several other pilot programs in New York, are part of a major effort by ACS to counteract its image as a “baby-snatching” police force riddled with the same racial and economic biases that beset actual law enforcement in the United States. Together, the programs amount to an experiment: to see whether one of the largest child welfare agencies in the country can change the dynamics that have poisoned its relationship with the vulnerable families it seeks to serve and must oversee. It’s a sort of idealistic gamble, deeply informed by critics who charge that child welfare agencies like ACS unfairly target the poor and the nonwhite, and treat all family crises with the hammer of child removal.

“It used to be in the Bronx projects that all you had to do was shout, ‘There’s a cop in the hall,’ and people would flee,” said Martin Guggenheim, a law professor at NYU and a national expert on child welfare. “Now you say, ‘ACS is on the ground,’ and people flee. That’s one of the saddest parts: This is a helping agency, meant to support poor families, and the parents are terrified of the very agency whose charge is to support them.”

Changing the way a massive bureaucracy has done business for decades is no small task. Success relies not simply on new, more benevolent programs like GABI, but also on convincing ACS’s community partners—the private groups contracted to provide foster care and preventive services—to embrace a new mission. It means convincing the holders of city and state purse strings—the ACS budget is $2.7 billion for 2019—to invest in experimental programs whose success won’t be calculable for years, and whose failures will be splashed across the media, potentially costing government officials their jobs. Above all, it entails convincing families who, for generations, have viewed ACS as a threat, to give it another chance.

If successful, though, ACS could create a more benevolent model for child welfare that would be followed in other cities and states. ACS, which conducts more than 60,000 investigations of families each year, is one of the largest child welfare agencies in the country—dwarfing many other states’ agencies entirely. Its size alone guarantees that whatever happens here becomes a national model. “Everyone in child welfare agrees that what’s going on in New York City is relevant to the work happening elsewhere in the country,” said Guggenheim. Instead of a government bureaucracy that is widely perceived as punitive and biased against the poor, ACS could transform itself into the type of agency that it wants to be: a resource families can turn to in times of trouble.

“There’s something to be said for why ACS partnered with us,” Murphy said to the mothers at the St. George GABI center. “They don’t want to operate out of fear, and they really want to be here to support people.” The women nodded, considering the idea. Finally, one of them spoke, “So you’re saying they want to change?”

For more than 150 years, child welfare policies have swung back and forth between two polarized notions of how best to serve vulnerable children: Should they be removed from troubled homes, or should their families be helped? Should “child protection” be the guiding principle, or “family preservation”? Where society lands on these issues has always depended on prevailing attitudes toward poverty. Reformers have long argued that taking children from poor families does nothing to address the root problem of poverty. In June, for example, Democratic Representative Gwen Moore of Wisconsin, a member of the Congressional Black Caucus who, as an 18-year-old college student, was temporarily forced to relinquish her own child to relative foster care, introduced the Family Poverty Is Not Neglect Act, which stipulates that children can’t be removed from families solely on the basis of poverty-related issues. “I went through the system, and was humiliated, and mistreated,” Moore said in a 2017 interview. “I see that there is a deliberate effort to destroy these families.” Moreover, children who are placed in chronically overtaxed foster care programs experience long-lasting trauma and, as studies have shown, far higher risk of teen pregnancy, incarceration, unemployment, and homelessness, compared to children who are left in families with similar problems. Conservative critics, however, have essentially argued—particularly during America’s periodic drives to crack down on welfare—that parents who can’t support their families are, by definition, unfit.

From the mid-1800s through 1929, New York City and other Eastern cities arrived at a draconian solution, shipping as many as 250,000 children from impoverished tenement families West to the expanding U.S. frontier. Children placed on “orphan trains” were offered for adoption at depot stops and churches along the way. (To modern eyes, many of those adoptions more closely resembled indentured servitude.) Then, in the 1910s, the pendulum swung the other way, as a movement arose to supply pensions to “deserving” single mothers, particularly widows, so they could safely raise their children at home. (What minimal help that was offered, though, was restricted almost entirely to white mothers, as were the New Deal’s welfare provisions two decades later.)

In the 1960s, things changed again, when the concept of child abuse was “rediscovered” by a group of doctors that included C. Henry Kempe, a pediatrician who coined the term “battered child syndrome.” Kempe’s label—which he described as deliberately “provocative and anger-producing”—helped lead to the establishment of mandatory child abuse reporting laws across the country. The idea was widely embraced, notes journalist Nina Bernstein in The Lost Children of Wilder, her account of the legal battle to reform New York City foster care, because casting child abuse as a “classless” phenomenon—no more endemic to the poor than the rich—allowed politicians to isolate child welfare spending from the larger anti-poverty programs of the Great Society, which were by then already losing support.

But the focus on child abuse, which might seem a positive, child-oriented development, resulted in demonizing parents—most often parents of color—whose children suffered because of the environments they were born into. “What was understood by some advocates as a social problem rooted in poverty and other social inequalities became widely interpreted as a symptom of individual parents’ mental depravity,” notes social critic Dorothy Roberts in her book Shattered Bonds: The Color of Child Welfare.

“It’s never been a classless problem, and it certainly is not today,” said Gottlieb. “If legislators say, ‘We’re going to pour these billions into supporting poor families,’ it won’t go anywhere. If we say, ‘We’re going to protect children from abusive parents’—if we label a demon—then the money can follow that.” In the child welfare system today, she said, “everything we do for families is set up around the idea that ‘We have to protect our children from you.’”

In the 1970s, the class-action lawsuit Wilder v. Bernstein took aim at racial discrimination within the private agencies that handled New York City’s foster care with taxpayer support, but which systematically excluded black children. Black children at the time were relegated to harsh, decrepit juvenile reformatories, in which, in some cases, more than 80 percent of the kids hadn’t committed crimes but were simply would-be foster children. The racial disparity was so stark, Nina Bernstein notes, that the superintendent of one facility called it “a plantation.” By the time Wilder was settled in 1986, almost 15 years after it began, the city’s foster care system was starting to explode amid the aids and crack epidemics. By the early 1990s, there were nearly 50,000 children in the system—almost all of whom were black.

Politics at the national level only made matters worse, as the political establishment turned against welfare and began to argue explicitly that parents who needed support to raise their children had no business keeping them. In 1994, Newt Gingrich put it most bluntly: “We’ll help you with foster care, we’ll help you with orphanages, we’ll help you with adoption”—but not, as Bernstein noted, with money for family preservation, a position that was echoed in the Contract With America that Gingrich proposed later that year. By 1997, when Congress passed the Adoption and Safe Families Act, establishing a tight timetable for terminating parental rights and offering foster children for adoption, the campaign against keeping families together had become so forceful that one magazine headline read, “family preservation—it can kill.”

The force of the pendulum swing between child protection and family preservation is often driven by high-profile tragedies. In New York in 1995, Elisa Izquierdo, a six-year-old girl from Brooklyn, was brutally beaten to death by her mother after repeated reports of abuse from neighbors and Izquierdo’s school went unheeded by the city’s Child Welfare Administration and other city and state agencies. The case became a national scandal. Time magazine published a haunting photo of the girl on its cover, under the title, “a shameful death: let down by the system, murdered by her mom, a little girl symbolizes america’s failure to protect its children.” The Child Welfare Administration was abolished, and ACS was created in its stead.

Izquierdo’s death sparked what has become a familiar pattern of overcorrection, common in the aftermath of such tragedies, in which child welfare officials ramp up family separations, in an effort to avoid another catastrophic “miss.” Through the mid-’90s, notes a recent report by the Center for New York City Affairs, a policy research institute at the New School, the ACS caseworkers’ union even counseled its members with the grim slogan, “When in doubt, pull ’em out.” And they did: In the three years following Izquierdo’s death, the number of children taken into ACS custody increased by 50 percent.

Family preservation advocates like the National Coalition for Child Protection Reform call this a “foster care panic.” It is hardly unique to New York. In the two years following the 1993 murder of a toddler in Illinois, the state’s foster care system grew by 44 percent, rendering Illinois children more likely to end up in state custody than anywhere else in the United States.

But the need to intervene more is the wrong lesson to take from tragedy. “Children fall through the cracks not because child welfare agencies are devoting too much to family preservation,” Dorothy Roberts writes, but “because agencies are devoting too much to child removal.” When there are too many children in foster care, she argues, there are neither enough foster homes to care for them, nor enough caseworkers with adequate time to identify those children who are truly at risk. Indeed, NCCPR notes, three years after the foster care panic began in Illinois, child deaths in the state had increased by 17 percent. Moreover, the focus on child protection creates perverse incentives for caseworkers and welfare agencies. “There has never been a preventive services worker in the history of child welfare who has ever been penalized for not helping a family enough,” said Gottlieb. “But they are penalized all the time for not doing enough to protect the kid.”

In 2016, a similar panic flared again, following the deaths in New York of two children whom ACS had left in their homes. That September, a six-year-old boy from Harlem named Zymere Perkins was allegedly beaten to death by his mother’s boyfriend just weeks after an ACS caseworker closed his case. Two months later, three-year-old Jaden Jordan of Gravesend, Brooklyn, died. ACS had received an anonymous report that the boy was being kept in a dog crate, but for two days, caseworkers couldn’t locate him, because they had been given the wrong address, and staff didn’t know how to find the correct one in their system. Like Perkins, Jordan was allegedly beaten to death by his mother’s boyfriend.

The ensuing public outcry was tremendous. “How ACS Failed Him,” read the headline of a New York Post article detailing the abuse Perkins suffered. The city’s other tabloid, the Daily News, lambasted Perkins’s caseworker with a cover story that declared, “she let him die to get promoted.” Then–ACS Commissioner Gladys Carrión, a reformer who had focused on preventive services intended to keep children out of foster care, resigned under pressure.

Since then, ACS has been eager to repair its image. In June, it launched a public relations campaign featuring videos and subway ads with children and parents who’d been involved with the system declaring, “ACS fought for my family.” In June, the agency unveiled a “CPS appreciation week,” to honor New York City’s child protective specialists, its “first responders” for children. And its new commissioner, David Hansell, who succeeded Carrión in February 2017, has been courting the media in an effort to improve public perception of the agency.

“We’ve had a couple of terrible tragedies,” Hansell told me, “and the dynamic we’ve seen over and over again—not just in New York City but across the country—is that a terrible tragedy happens, it gets a lot of attention in the public, there are investigations, and so on. It leads the child welfare agency to be reactive and defensive and to be more draconian.” He vowed to address this cycle by focusing on the root causes that underlie tragedies like child deaths, rather than seeking individuals or communities to blame.

Yet from 2016 to 2017, the number of children placed in foster care in the city increased 13 percent. Hansell attributed the increase not to caseworker reactiveness but to a rise in public reporting—up 7 percent since 2016. However, in the year and a half following Perkins’s death, ACS has also presided over a 54 percent increase in the number of cases it brought to family court, and a roughly 30 percent increase in emergency removals—when ACS takes a child from parents before even seeing a judge. As a result, warned a July report from the Center for New York City Affairs, ACS staff caseloads have increased, families have been put on months-long waiting lists to receive preventive services, and family courts have been so swamped with cases that attorneys say it’s led to “a new level of dysfunction,” with delays and deferrals “that impact every family in the system.”

I got a sense of this when I visited the Bronx Family Court, an imposing brutalist structure not far from Yankee Stadium. In June, in a windowless waiting room on the seventh floor, I watched a distraught young mother—African American, like almost everyone else there—approach the court clerk and two white lawyers who were complaining about the bad courthouse Wi-Fi and their children’s college grades.

“Excuse me, what’s going on?” she asked. Her court- appointed attorney had left New York without anyone telling her, and her new lawyer hadn’t shown up. “I come every time [ACS] sets court appointments, and they never show,” she said. The clerk apologized, then looked to one of the attorneys, who was there representing ACS: Maybe he should talk to the agency about why the mother’s caseworker hadn’t been in touch. The mother walked back to a wooden bench, where a young boy and an adult man waited silently. “This happens every day,” she said, angry to the point of tears.

Inside one of the courtrooms, another African American woman, middle-aged, with braids pulled into a side bun, sat at the center of a U-shaped table, listening as her public defender explained that she’d been accepted to an in-patient substance abuse program that allows parents to keep their children with them. A court-appointed guardian, there to represent the woman’s young daughter, objected, saying it was too soon to place the child back in the mother’s custody, and that the city should wait to see if she could stay sober. An ACS attorney concurred, arguing that the mother should only be allowed to see her daughter before entering rehab if she passed a drug test that day. The judge agreed to both requests, then asked the lawyers about their vacation plans before setting a date to reconvene in a month. The mother, whom no one had addressed directly, started to cry.

In Highbridge, a poor, predominantly African American and Latino neighborhood not far from the Bronx Family Court, a new program called Circle of Dreams opened in April. It is one of three Family Enrichment Centers that ACS is testing as part of its reform effort. Funded by ACS but operated by existing community nonprofits, the FECs are open to parents and nonparents, teenagers, and seniors alike, and can include food pantries, résumé workshops, parenting groups, art classes, or just hang-out spots. Circle of Dreams is managed by Bridge Builders, a local group that focuses on family preservation. ACS is providing $450,000 in annual funding for the next three years.

From the street, you could easily miss the entrance: a side door to the basement of a large prewar high-rise. Inside, however, the stairs lead to a series of bright rooms that seem to open endlessly onto one another. Chairs are clustered around a flat-screen TV streaming an image of a flickering log fire. There’s a table with orange juice and sweet rolls. An alleyway covered in paver stones leads to a patio with a child’s basketball hoop, a porch swing, and ivy-covered walls. There’s a playroom, computer stations, a dining area with flowers on the tables, and a den in the back, where, on the day I visited, women had rolled back the carpet to host an impromptu Zumba class.

The center’s programming is driven by client demand—asking people what they need, and also what existing strengths the center can tap into. (In Highbridge, the almost ponderously deliberate practice of soliciting community feedback meant that some of the center’s brightly painted walls were still bare in June; the process of polling the community on what art they wanted hadn’t yet concluded.) In its first month of operation, the center hosted a “parent café” in the dining room, gathering parents from widely different backgrounds for food and guided discussion on topics like how to help your children talk to you. Unlike the GABI centers, which are focused on parents with open ACS cases, the goal of the FECs is to strengthen the community and reduce the need for ACS interventions. “Parents are isolated,” said Alida Camacho, Circle of Dreams’ director. “If you talk with most families who have cases of neglect, you’re going to find that they’re decent parents, that in a lot of areas they do have good parenting skills. But there are some areas where they don’t.… In centers like this, we’re hoping that we’re going to hear it firsthand before something becomes an issue.”

Since the 1990s, when New York City placed almost 50,000 children into foster homes—10 percent of the country’s entire foster care population—its child welfare agency has reduced the number of child removals significantly. Today, approximately 9,000 children are in New York City’s foster care system—a sharp decline that is due, at least in part, to the aid that ACS’s existing prevention programs provide. Yet ACS’s successes have been tempered by the fact that, because many poor parents view ACS as inherently dangerous, they routinely walk away from the programs that are designed to support them, rather than invite child welfare into their lives. “So many people are scared that reaching out for help can mean ACS involvement,” said Rise’s Jeanette Vega. “So they don’t reach out, they stay in their homes, and they don’t get help for their problems.” The distrust and fear that poor parents feel are roadblocks that ACS must overcome. “No child welfare system is going to work well when parents run away from the help that they’re being offered,” Martin Guggenheim said.

Given their experimental nature, Circle of Dreams and the other FECs are still figuring out how to define success. For now, they are mostly collecting anecdotes: a mother who came in looking for assistance with an electric bill and left with money management mentoring and a prom dress for her daughter; the teenagers who enjoy free pizza after school; the women dancing in the next room. The benefits, to a certain extent, are intangible. “We can count numbers,” said Crystal Young-Scott, director of ACS’s FEC program. “But what does that Zumba mean to these women?”

The most important aspect of the centers, however, may be the fact that people can use them with a large degree of confidentiality. At Circle of Dreams, there’s no intake process, no tracking database, no case management services where ACS checks in on parents. Employees are still mandated child abuse reporters, required by law to call the child abuse hotline if they suspect that a child is being mistreated. But an explicit goal of the center is to dispel the notion that asking for help automatically triggers ACS involvement. “Everyone is so used to when you receive services, someone’s going to open a case record,” Camacho said. At Circle of Dreams, however, “when people come in, you don’t have to sign in if you don’t want to.”

Kailey Burger, ACS’s assistant commissioner for Community Based Strategies—a new division within ACS’s prevention division—worked as a lawyer in the Bronx Family Court in 2014, handling juvenile justice cases, before coming to believe that courts weren’t the solution. “By the time the kids are in those systems, so many other systems have failed,” she said. She decided to move “upstream,” to ACS, with the hopes that the child welfare agency could fix its poisoned relationship with poor communities of color and allow families to feel comfortable enough to ask for help before things reached a crisis point. In 2016, Burger partnered with Dr. Jacqueline Martin, the deputy commissioner of ACS’s prevention division, to pursue initiatives like the GABI program and the FECs. The goal, Burger said, was to help families “in a way that they retain dignity.”

Through these pilot programs, Martin and Burger have been rethinking the role of ACS. “What if families could really pursue their potential? What would they need to do that?” said Martin. “What if race and ethnicity didn’t matter? What kind of child welfare system would we need?” And more than anything else, they believe that ultimate success depends on ACS overcoming its toxic history with the families it wishes to serve. “We want this to be a new way of work,” said Burger. “Not working on or for a family, but partnering with them for as long as they want. And then we’re gone.”

Reformers who have spent years fighting for parents condemned by the system are still cautiously optimistic. ACS’s new initiatives are only pilot programs, and they involve a fraction of the families that the agency works with each year. And if ACS’s goal is to reduce its presence in parents’ lives, statistics suggest that the opposite is true. From 2005 to 2017, the number of cases ACS has substantiated annually has grown from 33 percent to 40 percent. And the number of families ACS has placed under court-ordered supervision has increased from 1,947 to 7,490 per year over that same period. “The presence of ACS in neighborhoods is higher, and that’s a bad change,” said Nora McCarthy, the director of Rise. “If they’re really committed to changing dynamics, they need to change the dynamics in which they’re hauling so many families into court.”

“On paper, ACS’s heart is in the right place,” said Ginelle Stephenson, a social work supervisor at the Center for Family Representation, which provides lawyers to parents with ACS cases in Manhattan and Queens. But the new approach doesn’t seem to be trickling down to the ACS rank and file. In meetings with caseworkers at foster care agencies, she said, well-intentioned bromides about not blaming or shaming parents tend to be forgotten by ACS workers loading up case plans with more services than parents can manage. “A lot of what we do is say, ‘She doesn’t need that right now,’” said Stephenson. “It’s supposedly voluntary, but there’s a lot of undertone that, ‘If you don’t, we’ll be watching.’”

And there’s still a concern that, despite their stated goals, the new pilot programs could become avenues for more ACS involvement in families’ lives, rather than less. “A really key test of whether there’s a shift is when families go into FECs and see what’s offered, how often is there going to be a report called in to a hotline,” said Chris Gottlieb. “I hope these will be helpful enough that they will outweigh that risk, but the more the staff sees themselves as monitors of the poor community, the less helpful it will be.”

Burger said she understands the skepticism, given the way ACS has traditionally worked with poor communities, and the footprint its other divisions still have. “Every time I go out and say I work for ACS, people say this is pie in the sky,” she said. But she hopes the new programs will demonstrate ACS’s commitment to a new way of doing things. “It’s on us to continue keeping our word.”

The pilot programs may be small in scope, but they could have a far-reaching impact on the child welfare landscape. Over the next year and a half, most of ACS’s existing contracts for foster care and prevention programs will expire, providing the agency with an opportunity to implement its reform agenda on a wider scale. The programs that ACS works with going forward will determine the values and direction of the agency for at least the next decade. To Martin and Burger, it’s a chance to create a more socially just child welfare system.

The ultimate challenge, though, may not be whether ACS can develop more supportive programs—or even whether it can get poor families to trust the agency again. It’s whether society as a whole can stop criminalizing poverty and embrace the idea that poor families are worthy of compassion. Even the best preventive services will flounder if they continue to be surrounded by a broader landscape in which caseworkers, investigators, attorneys, and family court judges treat poor parents as criminals. Even the most generous of programs cannot make up for government policies that force poor children to live in unsafe housing, drink lead-poisoned water, and go without adequate health care and education. “The whole existence of ACS lets us pretend that we’re protecting children,” said Emma Ketteringham, the managing director of family defense at the Bronx Defenders, a legal nonprofit that represents parents with ACS cases. “But if child protection was at the center of our priorities, that would require the government to rethink its relationship vis-à-vis children.”

On the whole, however, government policy continues to adhere to the Social Darwinist conviction that the wealthy are most deserving because they are wealthy, and the only reason poor people are poor is because of some personal flaw. The overarching narrative, Martin Guggenheim said, is that “the only thing wrong with poor children is their parents.” Overcoming that ideology will require us as a society to confront a harsh reality. “The truth about what’s wrong with poor children,” Guggenheim said, “is they were born in America, in a system that doesn’t care about them.”