In Los Angeles, in 1947, 14-year-old Susan Sontag would take the trolley to the “enchanted crossroads” of Hollywood Boulevard and Highland Avenue to listen to records and read Partisan Review, attempting to “ward off the drivel” she felt submerged in. At night, she perched in her mother’s green Pontiac on Mulholland Drive, where she and her best friend would debate how many years Stravinsky had left to live, engaging in a “compelling fantasy à deux about dying for our idol.” Stravinsky was her god, and Eve Babitz, an Angeleno girl ten years Sontag’s junior, was Stravinsky’s goddaughter and another precocious “daughter of the wasteland”—Los Angeles. At 14, Babitz began her memoirs, entitled I Wouldn’t Raise My Kid in Hollywood. She would continue writing different iterations of this memoir for years to come.

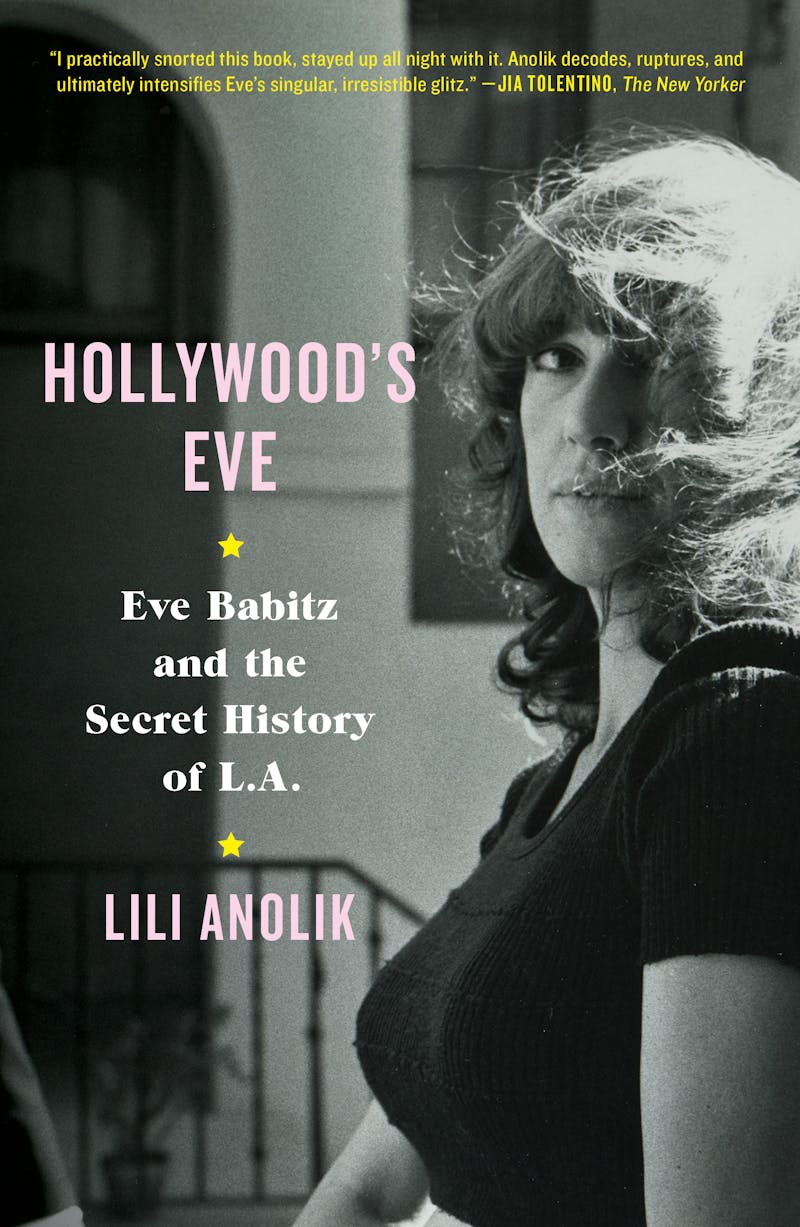

Though they both scuttled around Hollywood, Sontag was a self-described “zealot of seriousness,” Babitz a muse and a party-girl. Babitz was well-known in certain West Coast sets from mid-60s through the mid-70s, but until recently, she had lapsed into semi-obscurity, known to a broader audience mainly as an adjacent to the real-thing: the nude photographed opposite Marcel DuChamp at the chessboard; Jim Morrison’s paramour; the girl who wrote to Joseph Heller to inform him that she was a “stacked...blonde on Sunset Boulevard.” (“I am also a writer,” she added.) In a new biography, Hollywood’s Eve: Eve Babitz and the Secret History of L.A., Lili Anolik confronts Babitz’s contradictory legacy, composing a portrait of Babitz as a cultural figure—and writer—in her own right.

“People with sound educations and good backgrounds get very pissed off in L.A.,” Babitz notes in Slow Days, Fast Company: The World, The Flesh, and L.A., the languorous and conversational volume of ten essays she published in 1977. She admits that in Los Angeles, any attempt at logical sequence “gets lost in the shuffle.” This suits Babitz’s style, a slinking meander with a sense of breezy ongoingness and a quality of non finito. Babitz is not beholden to form or formality, and she never strains in her “sultry glimpses of this coast.” In the opening of Slow Days, she admits that “I can’t get a thread to go through to the end and make a straightforward novel.”

I can’t keep everything in my lap, or stop rising flurries of sudden blind meaning. But perhaps if the details are all put together, a certain pulse and sense of place will emerge, and the integrity of empty space with occasional figures in the landscape can be understood at leisure and in full, no matter how fast the company.

Her essays address the carefully-arranged geometry of a moment that quickly dissipates and rearranges itself, and whose recounting later sounds “like one of those horrible New Yorker stories from the thirties.” Babitz describes existing as though on the cusp of reality, circling the periphery of actual existence: “Anytime I want, I can forsake this dinner party and jump into real life.”

For Anolik, Babitz is, as Marilyn Monroe was, “an artist who was also a work of art.” Babitz idolized Monroe. When Anolik asks Babitz about the infamous photograph taken of her at 17, naked during a game of chess with Duchamp, Babitz talks about herself as an object of interest, describing how her “breasts blew up. I thought they should be photographed. You know, documented. For posterity.” Anolik argues that Eve was far from “passive and pliable”; she was “artist and instigator, wicked and subversive.” More than an alluring girl with a heroic interest in most inebriants, she was a thinker who could “convert that energy into something beautiful.”

Anolik discovered Babitz in 2010 via a misattributed quotation in Joe Eszterhas’s memoir, Hollywood Animal. She locates and devours Babitz’s out-of-print books, then, wanting desperately to talk to her, tracks her down in a condo in West Hollywood. They eventually establish a relation bordering on a rapport, and Anolik finds that Babitz talks like she writes. Much of the biography progresses in the manner of Babitz’s prose, centering on descriptions of scene and anecdote. Also following Babitz, Anolik bluntly informs the reader that her own book “won’t attempt to impose narrative structure and logic on life, which is (mostly) incoherent and irrational.” Dates and facts and “verifiable sources” are of glancing interest, though we learn that Babitz was born in 1943 and attended Hollywood High; that her father Sol was the first violinist for the L.A. Philharmonic, and that her mother, Mae, an artist, hosted parties packed with musicians.

Babitz’s writing was never beholden to feigned seriousness. The sketches and autobiographical riffs in Eve’s Hollywood, Babitz’s first collection, contemplate subjects from the Hollywood Branch Library and Bunker Hill to Cary Grant and Xerox Machines. In Slow Days, she writes an essay ostensibly about a weekend in Bakersfield, but it devolves pleasantly into an explanation of grape-growing and a man who “looks like a Marlboro commercial up close.” In another piece, Babitz coaxes an acquaintance into coming to a party by dangling in front of her the chance to meet her color-blind friend. “Nikki, like me, was a slave to color and thought about it over and over,” she explains. “For someone to be without that sense would amaze her, fascinate her.” Babitz is perpetually interested in tint and hue. At its most incisive, her writing is a form of pointillism, acutely depicting the particular shading of the hours of an afternoon. She dedicates Eve’s Hollywood, to—among a hundred other things—the color green.

In her work, Babitz plops down in situations where she is “luxuriously involved in an unsolvable mystery, my favorite way to feel.” She basks in what others whine about, a beguiling loiterer whose observations are at times reminiscent of the inactive activity of Geoff Dyer. (Of a crowd at a Dodgers game, Babitz writes: “I love hordes. They screen out free choice; you’re free at last: stuck.”) She sustains a humorous and conversational tone, mentioning her clever opinions on literature in an unassuming way—she remarks that she slipped a lover a book by M.F.K. Fisher essays, saying “read these, they’re like Proust with recipes.”

Often untethered, she samples various lives but seldom becomes attached: “Early in life I discovered the right way to approach anything was to be introduced by the right person.” Or, as she writes about a man she meets: “I yearned to be invisible and he led a real life.” The biography offers telling glimpses into Babitz’s relationship with the photographer Paul Ruscha, recounting how he gave her a combination of intimacy and distance—a shared life lived mostly apart, just close enough to keep each other from floating away. Anolik admires Babitz’s self-possession, reading Slow Days—a slim yet languid volume, subtle despite the fact that it’s an act of seduction, addressed to a lover who won’t pay attention to her—as evidence of Eve’s increasing patience and restraint. To her, it shows Eve so in control that “she can abdicate it.”

“A thing about Eve I’ve learned,” Anolik writes of her unreliable subject-narrator, is that “though she never lies, she’s not always to be believed.” Anolik chooses to mythologize Babitz as Babitz mythologizes herself, writing more as a disciple than as a journalist. Her biography starts out in second person singular, written as if addressing her treasured Eve: “and then there’s your brains. You’re never not reading: Dickens, Trollope, Woolf, Proust.” Like Tracy Daugherty in his unauthorized biography of Joan Didion, The Last Love Song, Anolik falls at times into a pseudo-emulation of the lyrical and discursive—diverting, even—aspects of Babitz’s prose. An adoring acolyte of Babitz, she circles Babitz’s contradictory traits, her “guileless innocence and lethal knowledge all at once.” She enunciates her “naturally romantic disposition,” her sense of “the melodrama of the image” and her instinct toward the “cinematic.”

Anolik calls her book a “love story” about Babitz. There is no pretense of objectivity. “My love for her was pure, without irony or qualification, and I wanted to keep it that way,” she admits. Embraced fully, this sort of biography—a send-up of the absurdity and impossibility of biography itself—is genre of its own. But Anolik verges on idolatry: She even puts off reading Babitz’s Jim Morrison piece lest she find out that she disagrees with her beloved subject. The pitfall here is that though Anolik fills in lively background and context, a more compelling narrative emerges from Babitz’s own memoiristic writing. Anolik too frequently gets waylaid thinking about her own role as Babitz’s interlocutor, and her in Babitz’s resurgence: “Isn’t that the writer’s ultimate fantasy,” she muses, “that a thing he or she writes has an actual effect, changes the world in a visible, tangible way?” She laments that “forming an emotional bond is beyond Eve at this point.” Babitz was “unwilling or unable” to accept her affection.

Anolik’s book includes a lengthy discussion of Babitz versus Joan Didion, a rambling comparison that is only instructive in how it elucidates the frequently tenuous position that Babitz occupied as a writer. She shared a firmament with others, but had for a long time no ground of her own to stand on, subsisting mostly on her charm until Eve’s Hollywood was published in 1974 when she was 31; a lot of writing by and about Babitz focuses on her pedigree and her looks and her various lovers. While Didion had a reputation and a byline and a family, Eve’s position was far shakier, Anolik writes:

she had nothing tangible or durable to rely on, only such delicate and fragrant qualities as an ability to captivate, a talent for amusing. She was there on the pleasure and whim of people better known and more powerful than she.

Yet Anolik’s act of compare and contrast between Play It As It Lays and Slow Days, Fast Company becomes overextended and reductive. She says, for instance, that Babitz, unlike Didion, is “never a bummer.” Yet she fails to take into account Didion’s countless works of journalism and essays about California, including Where I Was From, Didion’s consideration of her native state, an incisive love-note of its own. Their Californias were different; as Didion famously said, “anyone who talks about California hedonism has never spent a Christmas in Sacramento.” That doesn’t mean that Babitz’s literary career was a response to—“nay, a rebuttal of”—Play It As It Lays. Anolik expresses her odd personal dislike of Didion—her “homicidal designs” against her own personality and her “cynical” and “silly, shallow” novel—because she wants to canonize Babitz as Didion’s replacement.

Toward the book’s end, Anolik worries that she initially presented a sentimentalized version of Eve, turning her into a “loveable eccentric” instead of the “seriously, radically strange” and occasionally impetuous woman she is. But the biography also shows snippets of the Babitz from a perspective that she herself would never give the reader. In interviews with Babitz’s family and paramours, Anolik dips into the dark underbelly of glamor, when the washed-up girl-about-town emerges from her bathtub covered in bruises, with a bloody nose from too much cocaine. At times, these broader shots aim to deepen an understanding of Babitz (though at moments they can also seem gratuitous). After Babitz dropped a lit match on herself while lighting a cigar at the wheel, she gave up writing. Now she mostly stays home, where she listens to conservative talk shows and, in Anolik’s telling, has to be tempted with churros and tabloids and e-cigarettes in order to come outside and talk.

Raymond Chandler wrote that “Hollywood is easy to hate, easy to sneer at, easy to lampoon.” In Slow Days, Fast Company, when Babitz returns from a trip, she remarks that “I long for vast sprawls, smog, and luke nights: L.A. It is where I work best, where I can live, oblivious to physical reality.” A man who writes Babitz a fan letter from London says he has a piece she wrote pinned up on his wall, because it explains California better than he ever could. When people ask him what it’s like there, he gestures to her prose. Babitz’s work isn’t about the feeling of displacement, but rather about a sustained cultivation of a sense of place—many of her essays read as if she were writing a “Goodbye to All That” to her own idiosyncratic version of Los Angeles, crucially devoid of the part where she curdles on the city. She manages to be both rooted and adrift.

In her bungalow, she writes about Updike and Henry James, but also basks in the sun drinking tequila and noticing things like “the moment when a man develops enough confidence and ease in a relationship to bore you to death.” Babitz proceeds almost blithely impervious to the forces of nature or history (she spent the Watts Riots in a penthouse at the Chateau Marmont.) She watches a family of overdressed tourists who have come to see Hollywood during the Santa Anas. It is not what they had hoped. They stand at the intersection of Hollywood and Vine on a windswept 105 degree morning—“an actual tumbleweed careened into them”—and sigh despondently at the anti-climax. Hollywood exists only as “the ruins of an empire of the self-enchanted,” explains Babitz. For her, this is home.